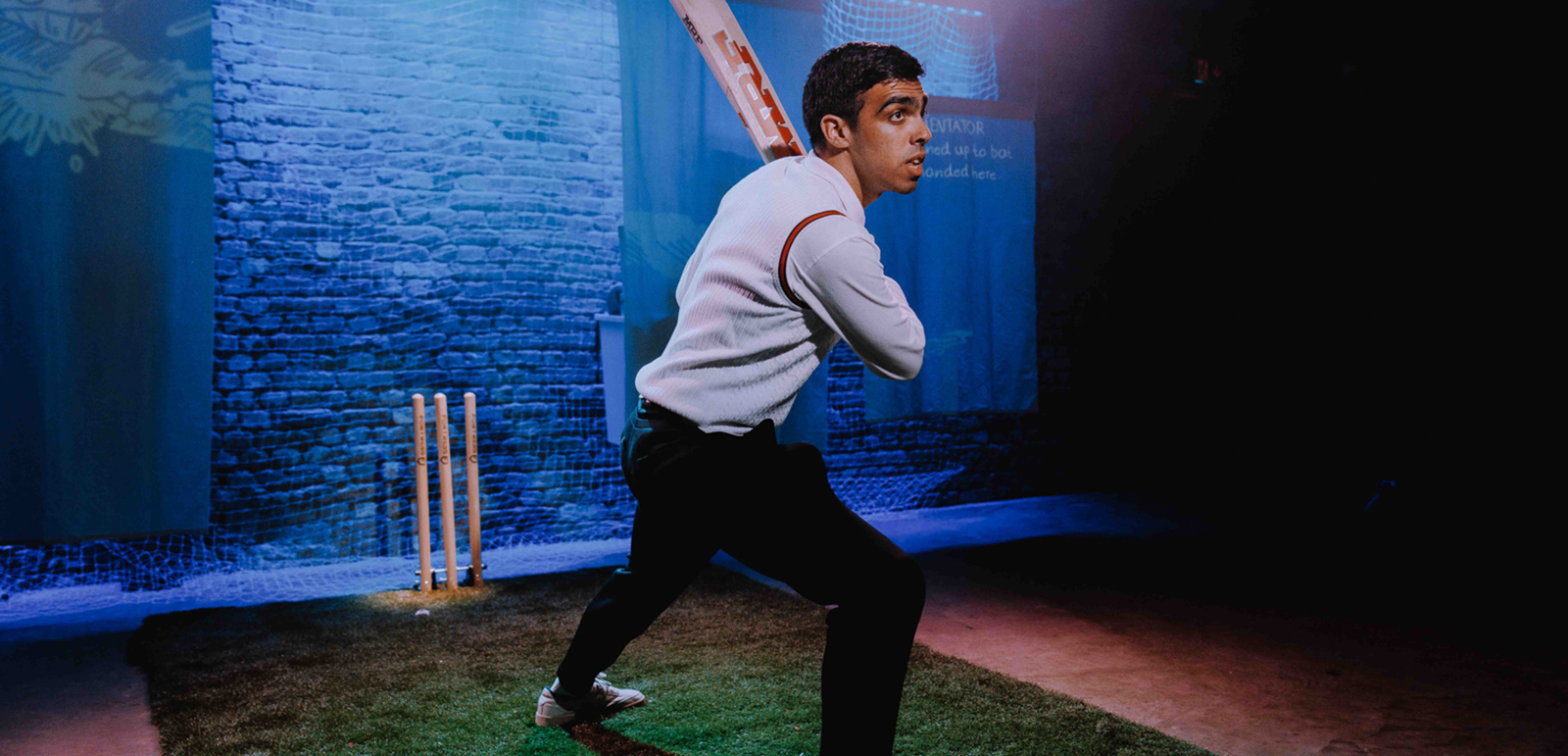

An evening of theatre to bowl you over

The play Duck takes audiences back to a tumultuous time for UK Muslims, seen through the eyes of a teenage cricket star

–

It is summer 2005. England have beaten Australia to win The Ashes for the first time in nearly 20 years and the 7/7 bombings have shaken London, killing 52 people and injuring hundreds more. Those historic events form the backdrop of Duck, a new play that tells the story of Ismail, a British-Indian teenager set on becoming the youngest and best batter his private school’s cricket first team has ever had.

As the title suggests, things do not go to plan, on or off the pitch. In addition to Ismail’s sporting challenges, the drama explores racism, bullying, police violence and how it feels to grow up in a particularly tumultuous time for British Muslims.

“Ismail is Muslim, he’s brown, and he then has to deal with these things and figure out what it means to be 15 at that time in this place,” said Maatin, Duck’s creator.

The play, which opened at the Arcola Theatre in east London on 29 June and runs until 15 July, is a one-man show starring Omar Bynon. Maatin began to develop the script in 2020 through the Hampstead Theatre’s INSPIRE programme, which each year gives a group of writers the opportunity to work on a full-length play, mentored by the award-winning playwright Roy Williams.

Maatin, 33, from north London, drew inspiration from his own experience of being the only brown, Muslim teenager in his year at an independent secondary school. Like Ismail, he was a talented cricketer, becoming captain of his team and even training at The Oval and Lord’s grounds.

However, from the age of 15, his interest in the sport waned. “Part of it was becoming disillusioned as a result of a coach who, similar to in Duck, took a dislike to me and made me feel excluded and unmotivated,” he said. “Once that happened, I stopped playing and haven’t really gone back to it since.”

As an avid theatregoer, Maatin has long had strong feelings about the ways in which Muslims are represented on the stage and the accessibility of cultural spaces for diverse audiences.

“I was going to the theatre a lot and I was often, if not always, one of the very few non-white people in the audience,” he said. “That really bothered me and I wanted to change it. I wanted to tell Muslim stories and root them in our community, to bring a whole new audience of people to the theatre. We live in this place, so we should see ourselves reflected in society around us. Islam is the second-biggest religion in Britain. Why aren’t we telling Muslim stories?”

Maatin began his journey as a playwright at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, graduating with an MFA in writing for stage and broadcast media. In addition to the Arcola production of Duck, Friday at the masjid, the first play he wrote, has been selected for the Royal Shakespeare Company’s new national competition, 37 Plays, marking the 400th anniversary of the publication of Shakespeare’s first folio.

Duck was partially inspired by the infamous “cricket test”, proposed in 1990 by the Conservative MP and former cabinet minister Norman Tebbit to assess the loyalty of non-white UK residents. Over the course of 85 minutes the script explores the complex and deep-rooted relationship many former British colonies have with the sport. Through Ismail — a character with many things in his favour, including class, wealth, sporting prowess and popularity — it also looks closely at the duality of South Asian British identity.

“I wanted to start the play where he’s never really had to consider: ‘Oh, I’m the only brown boy, I’m the only Muslim here’. When everything starts to go wrong, only then does he learn these things about himself.”

Duck feels especially timely, opening in the week a landmark report by the The Independent Commission for Equity in Cricket concluded that cricket in England suffers from “widespread and deep-rooted” racism, sexism, elitism and class-based discrimination. The document comes in the wake of the admission by Yorkshire County Cricket Club that the South Asian British player Azeem Rafiq was the victim of “racial harassment and bullying” in his time there.

While the play was written before the full details of Rafiq’s experience were made public, Maatin sees the case as a perfect representation of the problems he wanted to examine.

“In a setting like a cricket team, it’s always on the part of the minority person to fit into the larger culture,” he said. “When Azeem Rafiq shared his story, there were loads of people that were shocked and were like ‘This should never have happened to this man or to anybody’. But there were also people that were sceptical and were like, ‘No, you need to prove to us why this was racist. You need unequivocal evidence as to why this is wrong.’ I think that’s a really poor way of understanding racism, a really poor way of understanding how we treat one another.”

Maatin believes such attitudes contribute to a serious lack of South Asian representation at the highest levels of English cricket.

“A professional expert told me you see Asian kids participating in cricket teams all the time and then that completely fades out when it gets to the professional level,” he said. “Only now are people starting to acknowledge that maybe that’s a structural problem and that there needs to be more effort made in order to encourage Asian participation.”

By referencing the 7/7 bombings, Duck also highlights the ways in which the British Muslim experience has been affected by terrorism and government interventions such as the controversial Prevent Strategy — something its writer is keen to counter in all of his work.

“I believe that the British Muslims live in a precarious way today, and I don’t want to ignore that,” Maatin said. “I felt it was important to tell the story of an event that’s going to shape Ismail moving forward. But I also wanted to show joy.

“Muslim characters are often reduced to being angry or violent, but why not show us in our multitudes. This boy is a really good cricketer and he is really happy because of that. That’s true to a lot of our experiences, especially as innocent children, before the world starts to discriminate against us.”

Newsletter

Newsletter