The forests of memory

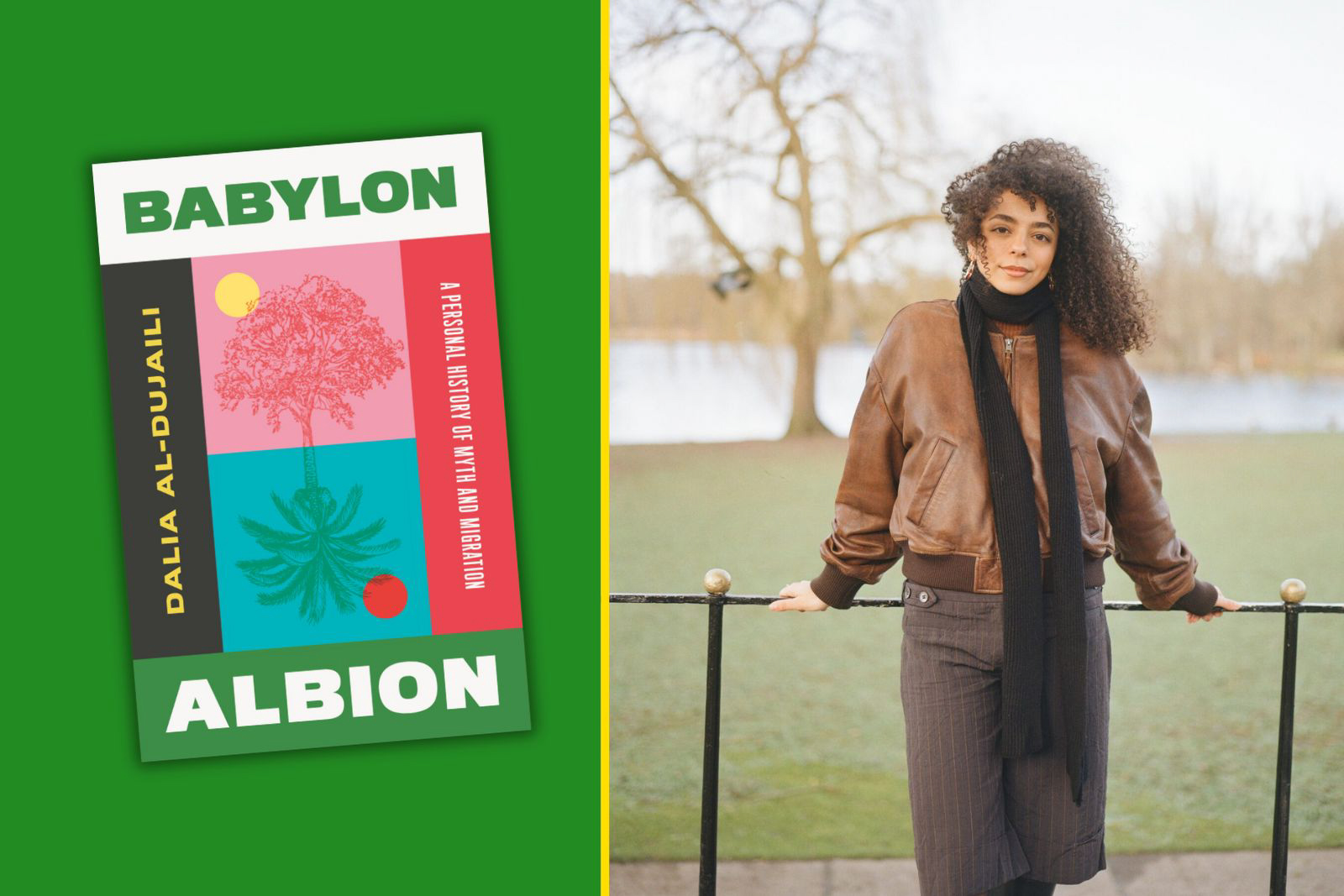

In new book Babylon, Albion, author Dalia Al-Dujaili examines the connections between land, migration and identity. For Earth Day 2025 we present an edited extract

Aberdeen

You balance a tray on your belly, bursting with a brother. You pour hot coffee for park goers. You walk the 20 minutes home. Your street is a row — like teeth, all the same, but slightly different — of beige and grey bungalows making up the Scottish suburb. On the weekends, you travel to the Highlands with friends you’ve made with names like Susanne and Jack. The grainy film from your camera can’t quite pick up the shades of your deeply olive skin, but it certainly picks up the jet black moustache atop your new husband’s thick lips.

Surrey

After giving birth to my brother, you enter a dark house cloaked in late September. You’re alone — you know your mother should be here for a time like this, but she is in Baghdad. Saddam has closed the borders and they won’t be able to leave for another several months. My mother’s name, Zainab, means “a fragrant tree or plant”. It’s a fitting name for a woman who speaks to the trees and plants as comfortably as she speaks to her children and siblings.

Mama grew up in an Iraq with people that she loved, but in an environment that became stifling as she reached adulthood. She felt trapped under Saddam — forced to celebrate his birthday (cake and candles and all) and watch his executions on television.

Albion

The ancient name for Britain. From the Latin “albus” meaning white, referring to the chalk cliffs along the south-east coast of England. They say the sailor hero Stormalong’s great ship scraped the sides of the Dover Strait as it passed through, creating the white cliffs of Dover. White cliffs steeped in myth; that is the first sight to greet travellers weary of papers, passports and immigration officers. Alban, the protomartyr of Britain, who converted to Christianity and was beheaded for it, also takes his name from albus. Saint Alban is considered the patron saint of converts, torture victims and refugees. The first martyr of Britain; a patron saint of refugees.

If you could plot and trace out on a map every path you’ve walked, every journey you’ve taken, every road you’ve travelled up or down, every sea you’ve crossed or not crossed, what kind of story would this map tell? What kind of person is etched from lines drawn across the land? My parents’ journey took them from Iraq to Surrey to Plymouth to Luton to Aberdeen and back to Surrey.

Iraq has a long history of migrations. A mosaic of people travelled through and settled in the Mesopotamian crossroads. It became one of the most diverse places in the world, like a rainforest brimming with biodiversity. But Iraq also has a long history of exiles. The 2003 invasion created at least 2 million Iraqi refugees to other countries. Iraq has seen the largest dispersal of any population since the second world war. In every migratory family there is a memory-keeper, a person who is unintentionally assigned (or inhabits) the role of collecting memories, like candies in a jar. We can imagine the memory-keeper in their emporium, shelves full of jars, their finger moving across rows of jars with labels for dates, or places, until they reach 6 February 1989.

My mother has never forgotten the day she arrived to live in the UK. She reminds us of the date every year, a mini anniversary. She remembers it as a peaceful moment. She remembers it as the “happiest day of her life”, though she also remembers that the border control officer at Heathrow airport held her and her younger sister up for so long with his suspicious questions that her uncle, who had come to collect them, drove away. They had to hail a black cab.

Sick of the war with Iran that had raged for eight years, Mama was desperate to leave Iraq. Prior to and throughout the war, Saddam had ordered the forced migration of around 300,000 Iraqis of supposedly Iranian origin to refugee camps on the border, along with Kurds and Shi’is. Thousands of men were also imprisoned. My mother was young and at the time in love with a neighbour of distant Iranian heritage. He was forced to leave overnight. She cried for months, her heart had shattered. She tells me that’s when her migraines began and never ceased.

I unbottle another memory; 3 March 1991. Over a decade later, in England, after my mother had married my father, they both attended a protest against Saddam’s regime following the Gulf War, where she spotted a familiar figure through the crowd. Stopping dead in her tracks, she called over to him and her childhood sweetheart turned to face her.

*****

I am 15 years old and I have my first kiss with the assistance of a tree in Stoke Park, Guildford — Astolat, home of Elaine the White. The barrier of foliage protects us from prying adult eyes. The trunk supports my back, the leaves under us are ruffled; my mother is incessantly calling my mobile, furious that I am late for her to pick me up.

There are many words for two groups in nature relying on one another for health and prosperity: co-dependency or interdependence, symbiosis, co-evolution. One afternoon in the Lake District in late summer, I watched a friend stare a tree up and down, voyeuristically, in awe. He revealed what I was innocent to. A blackberry bramble had wrapped its arms around a birch tree and climbed up its trunk and branches, offering her low-bearing fruit. It was the first time I’d seen blackberries growing from a tree rather than from a bramble bush.

He explained to me how the relationship between birch and bramble was a symbiotic one, one in which both parties benefit from each other’s resources. The bramble and the birch rely on one another to thrive. If one becomes too much like the other, they both weaken. How does the honeybee collect his nectar if he stands pretty and idle like the lavender? Or does the geranium grow tiny buzzing wings and attempt to fly away?

In our gardens, bees unintentionally collect pollen — that’s God’s sense of humour, I think, creating a creature who doesn’t know just how important its job is, who doesn’t know it’s doing a job at all. They carry their load to the next garden and the next and eventually onto the park and onto the forests and so on, until our landscapes are littered with new plant offspring. There is a reason our language pays respect to the bee’s work ethic — busy bee!

Pollination is vital for the reproduction of flowers and trees. Spreading pollen far and wide also encourages diversity in natural ecosystems, which enables plants to repel disease and adapt to various ecological challenges. The pollinator is one of the many life-givers. The honeybee is the figure of life’s delicate interdependence, as entire ecosystems balance on his delicate wings.

The top field at Polesden Lacey, the large estate that my village is built around, is glistening under the rising evening. The sky above conducts dramatic symphonies within its vast plains. I often drive here just to watch the sky catch fire at the close of each day. Today, the August heat has reduced to a simmer. A breeze glides by quietly, trying not to disturb me.

Tiny flecks start to appear, hovering over the horizon, bouncing like musical notes on the field. The dandelion seeds are catching the wind and beginning their migration to a new home in the evening air. These seeds have developed ingenious ways to germinate; after flowering in bright yellow, the weed closes up and days later, its white fluffy head emerges attached to dozens of small parachutes. The centre of these parachutes sense humidity in the air by absorbing water molecules. If the humidity is high, the trigger inside swells, closing the parachute. It will only take flight in the right, dry conditions.

We, too, are responsible for the pollination of dandelions. Flowers and their petals are some of the strongest supporting characters in British folktales and superstitions. Who has not picked a daisy’s petals and asked it whether “he loves me, he loves me not?” Or held a buttercup underneath someone’s chin to determine whether they’re fond of butter? As for dandelions, we blow on their seeds to make a wish, to calculate the time in fairy land or to determine if the one we love feels the same way.

A seed embarks on a journey, guided by forces beyond its control, driven by the need to find fertile ground. Over time, plants have developed ingenious ways to ensure their offspring can travel far from their origin, ensuring a future. The sycamore’s helicopter seeds use the wind to glide far from their point of origin. Milkweed seeds have fluffy, parachute-like attachments that let them float on the breeze, while maple seeds spin like tiny helicopters, gently spiralling away. Coconuts, protected by their tough outer shells, can drift on ocean currents for months, sometimes travelling thousands of miles before washing up on distant shores. Mangrove seeds, which sprout while still attached to the parent tree, are designed to float as well, dropping into the water and being carried to new areas where they can take root in nutrient-rich, muddy banks.

These migrations are often prompted by necessity — a search for resources or some other need for survival. Some plants, like grasses, release massive amounts of pollen into the air, hoping the wind will carry it to a receptive flower. The more colourful pollinators such as butterflies and hummingbirds are attracted to equally rhapsodic wildflowers and feed on nectar while inadvertently spreading pollen from one bloom to another.

Like seeds, humans must travel. Over generations, we spread into new lands, diversifying and enriching the environments we settle in, deepening our connection to the landscapes we encounter. This movement strengthens both the places we inhabit and ourselves, shaping the world we grow into. Today, more people are living outside their country of birth than at any point in history.

Though forest regeneration has been focused on recovering plant growth, reestablishing the codependent relationship between migrating land animals and birds is necessary to recover decimated forests. Over 80% of tree species in rainforests depend on moving animals for seed dispersal. And though ecology has generally held that birds and other airborne assistants such as bats carry out most of these tasks — with their ability to move swiftly across large expanses of forest and distribute seeds through droppings whilst airborne — it’s been recorded that from new forests, around 20 years old, to old growth, the seeds of most plants are distributed by land mammals.

In our forests, burdock and hitchhiker seeds have developed hooked or barbed surfaces that cling to the fur of passing animals, hitching a ride, to stop off and make a home in a new patch of wood, or in a different woodland altogether. The movement inherent to pollination maintains the rich diversity of life on Earth, ensuring survival through adaptation and expansion into new environments. The continual movement of both seeds and people creates an ever-expanding network of life rooted in change.

A culture, too, is an extended act of pollination. People who are on the move collect stories and drop them along their path like seeds, which then not only root themselves in that new land but pick up cues from the environment into which they grow, germinating further and influencing the ecosystem where they have been introduced, reproducing and even mixing with other life to create entirely new and unique life, new stories.

Babylon, Albion will be published in May by Saqi Books

Newsletter

Newsletter