House guests, hospitality and the hijab

In Namesake, a new collection of essays, the British-Palestinian author NS Nuseibeh examines modern life, identity and her family links to a formidable figure from early Islamic history

–

It is a well-known stereotype amongst Palestinians that we Jerusalemites are uncharacteristically unwelcoming. When a guest arrives, the old joke goes, the Jerusalemite says: “Welcome, welcome. When did you say you were leaving?” and “Wouldn’t you be more comfortable in a hotel?”

The summer before writing this essay, one of my closest friends came to stay with me, in the small house I was renting with five other people in Oxford. It was a last-minute and indefinite visit, sprung on both of us because of a work crisis of hers: a real test of my hosting ability. I was desperate to help her and house her: not only do I not get to see her very often — she lives across the world — but I knew how awful I’d feel in her place, how much it would mean to me to be offered a home. She showed up with two large suitcases and I readied myself. “Welcome, welcome,” I said to her, sternly shushing my inner Jerusalemite. “Please, stay as long as you like.”

As the days turned into weeks, she kept apologising and I kept insisting — both to her and to myself — that I was delighted to have her around. But the truth is, it was hard. As a graduate student, it is assumed that my time is my own, or, more to the point, when a visitor comes, that my time is theirs. There are no set hours, there is no office to go into. Work space, friend space, me space, it’s all the same: one rectangular wooden table in the cramped kitchen-cum-dining-cum-living room.

I would make a cafetiere in the morning and settle down in the seat directly in front of the oven (so close that its door will barely open), leaving the better one — by the doorway — for my friend. We’d sit there for hours and I would look at datasets I didn’t understand and talk with her and plan our lunch and wash our mugs and get emails from senior researchers who needed something written by me desperately urgently, and I would feel torn between all these sides of myself and all of my conflicting duties.

I’d worry that, between the both of us, I was taking up too much of the communal space in the house, so would try to make myself smaller, so that she could take up more room. I worried I was not giving her enough time, or comfort, or hospitality, and I worried that my housemates were getting frustrated by the imposition of an additional person in the house. I wanted to make her feel welcome, but I worried that my worry was too visible for that. The day she left, I burst into tears — yes, in part because I missed her. More so because I was relieved she’d gone. I could finally have my space again, my privacy.

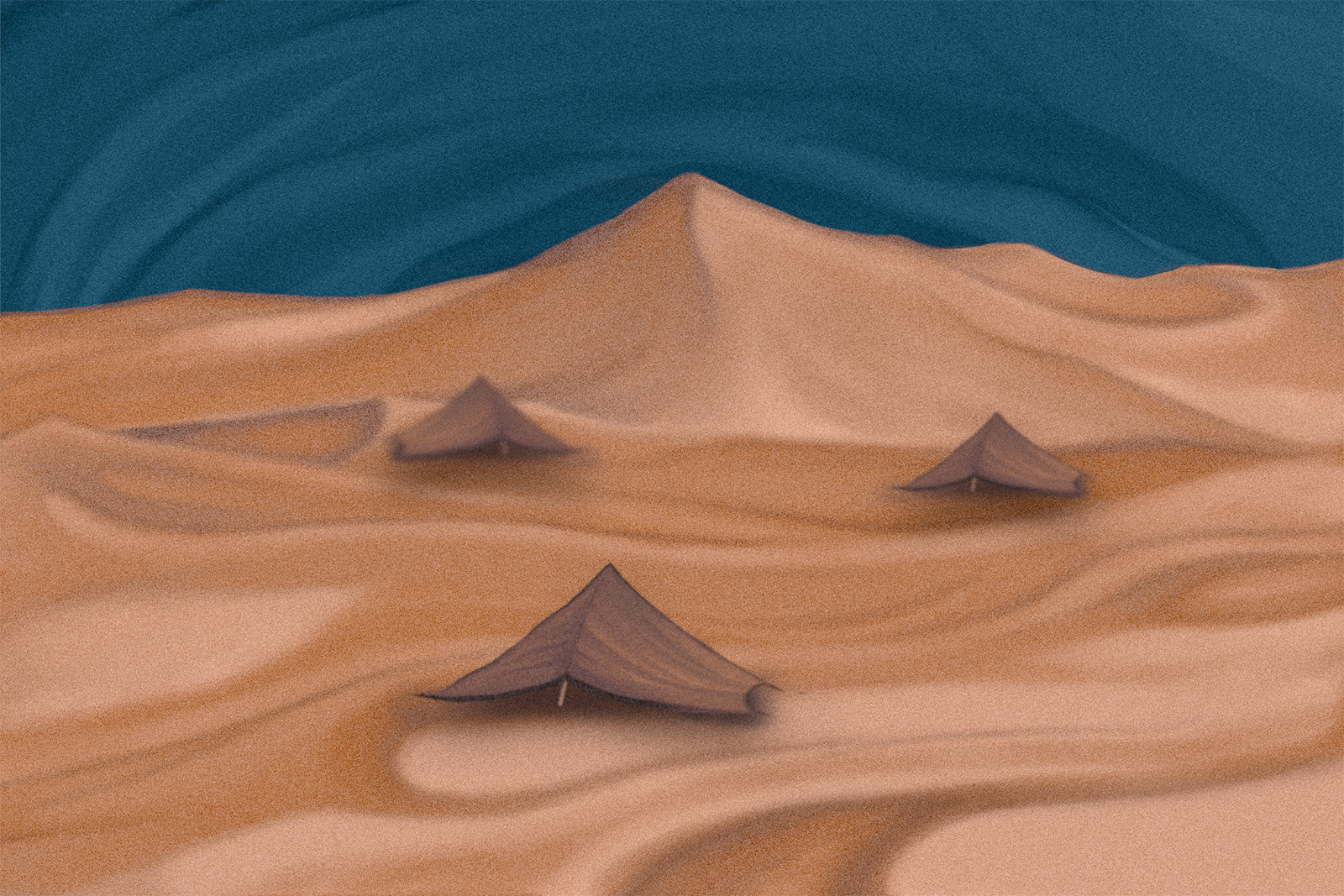

There was and there was not, in the depths of the past, a woman with very few boundaries. Nusayba bint Ka’ab al Khazrajia, a supposed distant ancestor of mine and a noted warrior, lived at a time with very little privacy. In Arabia in the 7th century, people lived in tribes, in compounds or in tents, with multiple wives to one husband and, in the case of many of the nomadic Bedouin tribes, multiple husbands to one wife — husbands who would often casually drop in on this wife individually or as a group, a constant stream of sexually demanding visitors. The idea of private time, of private space, would have been laughable.

That said, the way a Bedouin woman would divorce a husband was to simply turn her tent around so that the entrance would face away from him when he came over. I picture this like in a cartoon: a woman standing up to raise the structure and spin it round, a puff of smoke in the air, creating a threshold across which, it was clear, he was no longer welcome.

When Muhammad was at his peak as a prophet, living in Yathrib, Nusayba’s hometown, and with thousands of followers, his house was also the mosque: visitors and locals would come to pray with him, meet him, meet each other, put up tents and stay for days in his compound, using his personal space for social and religious purposes. This was a hangover from his early days as a leader, when he’d first arrived in Yathrib with only a few dozen followers and the local tribes — Nusayba’s among them — to welcome him. Out of his compound he’d created a centre for his teachings, and from that, a community. All welcome into his faith and into his home.

But that level of porousness was not, it seems, wholly sustainable once Muhammad became truly renowned. At that point, in 627 CE, after a particularly long wedding party of his, a conveniently timed divine revelation created a clear boundary between the private and the public.

One translation of the Quranic verse puts it particularly strongly: “Believers, do not enter the homes of the Prophet without permission and, if invited for a meal, do not come too early and linger until the meal is ready. But if you are invited, then enter on time. Once you have eaten, then go on your way, and do not stay for casual talk. Such behaviour is truly annoying to the Prophet, yet he is too shy to ask you to leave” (33:53). Perhaps Muhammad was also, in his soul, a Jerusalemite.

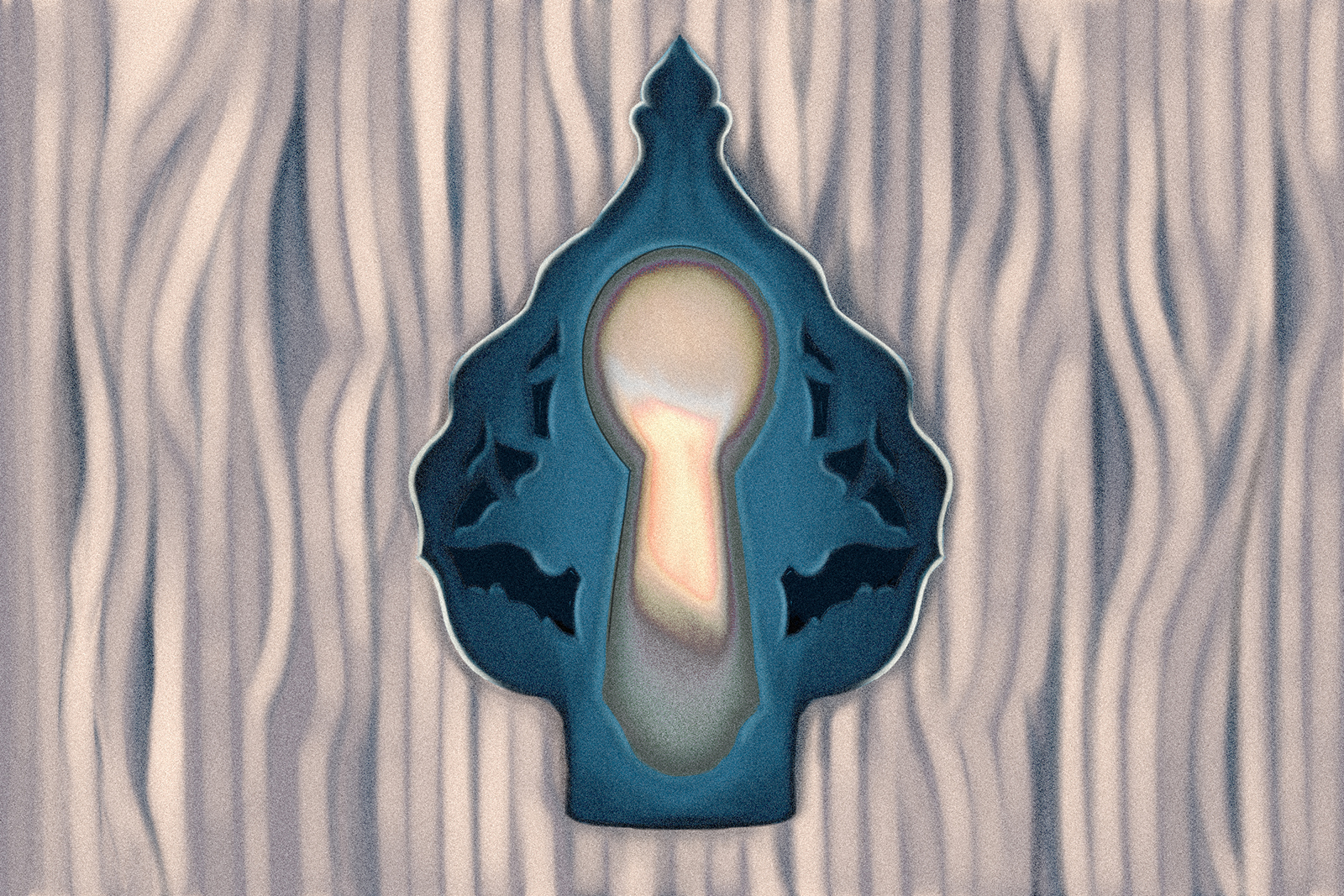

That same verse is also where the idea of the hijab first appears; in fact, it is commonly known as “the verse of the hijab”. The next sentence is “and when you ask [his wives] for something, ask them from behind a hijab. This will assure the purity of your hearts as well as theirs”.

There is a link, it seems, between the boundaries created in the home — where guests shouldn’t linger, shouldn’t wander in expecting food without being invited — and the boundaries created on the body. These are the spaces in which you are welcome, the verse seems to say, and these are the spaces in which you are not. Unlike the word “veil” in English, which is linked to the idea of covering up, the word “hijab” comes from the Arabic “hjb”, which means to screen, or to separate. In the Qur’an, the word “hijab” is also used to refer to the sunset, that brief borderline between day and night. I can imagine that, if I were living in a social and religious hub — where people were constantly coming and going, demanding my attention, trying to engage me in conversation — any sort of barrier would be a relief.

My grandmother, the heart of religion in my otherwise relatively agnostic family, hardly ever wore any kind of veil. Hijabs were a special occasion, going-out affair; they were made of light, wispy muslin that would flutter, slightly, as she wrapped it over her head. Once or twice as a young child I imitated her when she took me along to her jam’iya, her old ladies’ charitable society, feeling glamorous, like Audrey Hepburn on her holiday in Rome. It’s strange to think now of the source of that tradition: those wives of the prophet with their need for privacy, for boundary, for space. Even stranger to think how deeply emblematic the veil has become for Islam — the sign of everything from regression to rebellion.

It was only after years of living in the UK that I began to really notice the hijab. You don’t pay much attention to things that you’re used to, and when I was growing up, at least a third of those on Jerusalem’s streets usually had some sort of head covering, whether they were Muslim or Jewish or Christian. It was always there. Not something that evoked any particular emotion, neither alarming nor empowering, just present. But any kind of externally worn religiosity is, of course, noticed and noted in Europe, and so I began to see it too. A veil: synonymous with Islam, highlighting difference. Ironic, that a cloth designed to create privacy brings with it so much exposure.

Would Nusayba have donned a hijab of some sort, either before or after she converted? It’s highly unlikely. In pre-Islamic Arabia, in the early days (3000 BCE) of Mesopotamia, as in Europe both then and later, veils were often status symbols distinguishing the elite or the free from the poor or the enslaved.

As the feminist scholar Fatema Mernissi highlights, the Babylonian king Hammurabi imposed the veil for aristocratic women and actually forbade prostitutes from using it. Under the Assyrian empire, again, veiling was made mandatory for married women and concubines. Under the Christian Sassanid empire, aristocratic women were made to cover their hair. And even before that, in ancient Greek and Roman cultures, veiling marked out women of the upper classes.

That trend continued on throughout Europe well into the 20th century. Alexander Roslin’s famous portrait, The Lady with the Veil, painted in 1768, shows his wife looking seductively through a dark veil worn in the style of Bologna, where the best veils were produced, in which Roman courtesans and young women would cover their heads with floor-length silk in white, black, yellow, often also covering their faces, as they sauntered along stone-slabbed streets.

You are veiled because you’re valuable, untouchable, pure. In part, this is to do with visibility, of course — or rather, invisibility, hiding from view the desirable, the erotic or the beautiful — but veiling also creates a physical barrier, one that protects both from the elements and from other people. Veils are curtains drawn across the body, delineating the private from the public.

Multiple authors have pointed out that, in the Qur’an, the term hijab is applied only to the wives of the prophet Muhammad. It’s never applied to any other woman. Instead, it seems the hijab only started being worn by Muslims after Muhammad’s death, probably as a way to emulate his wives. Like many aspects of religious tradition, the veil’s importance has grown through time, through interpretation and imitation. So it’s extremely unlikely that Nusayba — part of the Banu Najjar tribe in the mostly poor, agricultural town of Yathrib — would have been important enough for a hijab.

Instead, she probably would have worn a tunic and a wrap called a jilbab, worn loosely and exposing the chest. It would have perhaps been made from a heavy, scratchy material, and some have suggested that this type of cloak sometimes would be worn over the head, covering an eye. Perhaps, then, in the hot, sandy desert, covering her head occasionally isn’t entirely unlikely. I picture her half-naked, a raggedy cloak wrapped carelessly around her well-built body.

I followed my friend’s visit with a visit of my own, to my parents’ home in Jerusalem. It still feels like my home, too, though it is not the same house I grew up in and too many of my school friends left the country years ago. So, leaving it is always a bit painful; there is always a sense of wrenching as we drive to the airport, as I stare at the mangy, worn-looking hills that dip and rise beside the Route 1 motorway that goes between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv.

It’s made more painful by the security processes at the airport, which are particularly bad if you happen to be a Person of a Suspicious Nature (Palestinian), and especially if you are a Puzzling Person of a Suspicious Nature (East Jerusalemite). I am put into a special line, given the highest security number, and searched extremely thoroughly. The idea of privacy here is gone entirely: two women in dark suits with lanyards round their necks, wearing white rubber gloves and strong perfume, pull out and examine my (slightly stained) thong, my pads, my beleaguered bras, my books and my water bottle.

They take everything out and pass the items between them displaying each one for the other guards, as well as all the fellow travellers who are sitting on the special seats in the special high security area. The entire inner contents of my luggage and handbag. The security workers pause when they get to my half-eaten granola bar, a comment is made, in Hebrew, and the bar is passed along and then back to the original security operative. My private life on full, laughable display.

A few seats down from me, a woman in a maroon tunic and veil is being asked by two of the guards whether she is wearing any jewellery underneath her clothes. She is struggling to understand them. They are communicating with her in English, a language in which she is clearly not comfortable. They point at the tiny cubicle beside the X-ray machine and make gestures to help explain that she will be going in there with them.

This is the strip-search area. They will go in with her, two women, and one of them will stand while the other asks the veiled woman to pull down her trousers and take off her tunic and under- shirt. The guard will then gently feel – through the slightly rough, see-through plastic of her gloves – inside the top seam of the woman’s underwear, underneath the wire of the woman’s bra, moving her fingers along the sensitive flesh in an act which, in other circumstances, would feel exceedingly intimate. Their bodies will all be absurdly, almost erotically, close.

I know this room and this routine because I have been in it many, many times. I have never worn a veil, though, so I don’t know how this would impact the process – I picture the woman undoing it all, struggling to move her arms in the circular motion necessary to unravel the material, avoiding the other bodies and the thin grey walls of the cubicle. I imagine the added layer of exposure this would entail, the sense of intrusion at a physical boundary so callously crossed.

Once on the plane, I see a different woman a few rows in front of me, also wearing a headscarf. She looks hot, her face flushed, but then again, I probably don’t look that different. Privacy doesn’t much exist in 21st-century planes either; the man in the seat beside mine has pulled out a mortadella sandwich, and now it’s me who has contorted my body in ways I didn’t realise were possible in order to move out of his way, his elbow occasionally darting dangerously close to my sternum.

At one point during the flight, I indicate to him that I need to move past in order to get to the bathroom; instead of getting up, though, like I expect him to, he simply sits back and grins. I smile tersely and do my best to squeeze through, my back towards him. I feel something on my bum as I manoeuvre out, my legs stepping over his, but I decide to ignore it. Maybe it’s him, maybe it’s the armrest, or even the mortadella. I don’t want to know. I spend most of the flight standing in the aisle.

I am constantly aware of these intrusions, perhaps especially because boundaries are in vogue these days: defining them, respecting them, navigating them. I am repeatedly told by well-meaning friends that I should set clear boundaries at work, or with family. Even Oprah has a step-by-step guide on boundary-setting, on how to cure “the disease to please”. We are meant to protect ourselves by being clear about what lines cannot be crossed: no work emails on weekends, no coming into my bedroom without knocking.

Boundaries, as one psychiatrist told the Wall Street Journal, mark “when your own autonomy and self-esteem are being invaded”. Not everyone’s boundaries are the same, of course. Ernest Hartmann, a psychiatrist and dream researcher working in the 1980s and 1990s, who is often credited with popularising the concept of personal boundaries, differentiated between those with “thin” boundaries, who experience the border between themselves and others as porous, and those with “thick” boundaries, who are rigid and well defended.

I am almost definitely of the former type – too sensitive to the incursion of others, but maybe it’s more general than that. It’s a particularly western thing, perhaps, and a particularly Muslim thing as well, to care so much about boundaries, to want clear lines between the public and private.

On a purely personal level, I think that a hijab — or even its more extreme version, the niqab — would bring me comfort, in the same way that the feeling of closing my eyes does, even now, as an adult, giving me the sense of invisibility. “If you should ask something of me, do so from behind a hijab.” A definitive, non-verbal way to create a boundary, and to feel some protection from the encroachment of the world.

To feel, as Mohja Kahf, the Syrian-American poet put it, “a tent of tranquillity”. Of course, the desire to create a boundary between myself and others isn’t a good enough reason to start wearing a hijab — related as it might be to the reason it first appeared in Islam — and I don’t have the faith required. More to the point, though, I’m just not brave enough. I would wear it so that I could hide, yet nothing makes you more visible, these days, than wearing a veil. What I would want from it is the space that it provided Muhammad’s wives; but maybe what I really want is to be able to say: “Don’t come in unless you’re invited. And definitely don’t linger.”

Being from Ramle, a city far from Jerusalem, my grandmother was always hospitable, almost to the point of farce. Her doors were never locked, even her garden gate — which leads out onto a main road — was almost always open. People from the street would often knock on her glass-fronted front door, or even just let themselves in, some to say hello, some to ask for money, which she would always give.

It was common for me to come over for a visit and find two or three people I didn’t know sitting beside her on the sofas. When we were clearing out her belongings from the awda rafi’a — the narrow room — in the back of the house after her death, we found a giant pile of thin mattresses neatly stacked in one of the corners. For the refugees, my dad said, after a moment. Her hospitality was as firmly rooted as her faith. She believed in letting people in, no boundaries necessary.

Nusayba probably also often had people around her in her own home: her sons, her clan, her tribe. She would, most likely, have had a deeply porous life, people coming in and out with increasing frequency and quantity as the prophet became more famous and drew to them more followers. (She would also likely have been part of the crowd milling around Muhammad’s compound: a lingerer.)

Her small agricultural village, her home, was transformed into a central hub for the converted. It would have been a change, for her, to see it flooded with so many strangers. Whether she ever had, or wanted, any privacy is impossible to know. What I imagine is this, at least: being in the desert, in this relatively remote village, it was easy to get away, at least. To wake in the night and slip out, unseen, mount a camel and wander, for a bit, under the stars.

My friend’s visit felt interminable, despite it only lasting just under three weeks. I began waking up with the dawn, just so as to have some time to myself: to work, to think, to just be. I found space and privacy in this way — through time — impossible as it was to find it through space. I felt, and still feel, ashamed of this reclusiveness. I desperately want to be porous, boundary-free, unveiled. But in reality I have always been a deeply private person, and shared space, exposure, frightens me.

I like walls and barriers — ironic, maybe, for a Palestinian — and the ability to shut others out. I like locks on my doors, and I tend to keep the curtains closed. My social media accounts are quiet places, dominated by the voices of others. Maybe there’s some epigenetic trauma in my desire for fixed territory — here is mine, here is yours — maybe national loss has seeped into my marrow, somehow. Or maybe it is just the Jerusalemite in me.

Namesake — Reflections on a Warrior Woman is published by Canongate

Newsletter

Newsletter