The nomad South Asian cricket team batting above its average

The United Cricket Club spent a decade fighting for the right to compete. Now it’s striving for a permanent home

One afternoon in April 2023, in a public park in Camden, north London, 13 men are spread out across a large circle of close-cut grass. They are standing stock-still and have been for some time. The only movement comes from a solitary individual, jogging gently towards a narrow, uneven strip in the middle of the circle, twirling his arm over his head like a windmill and sending a ball floating gently through the air.

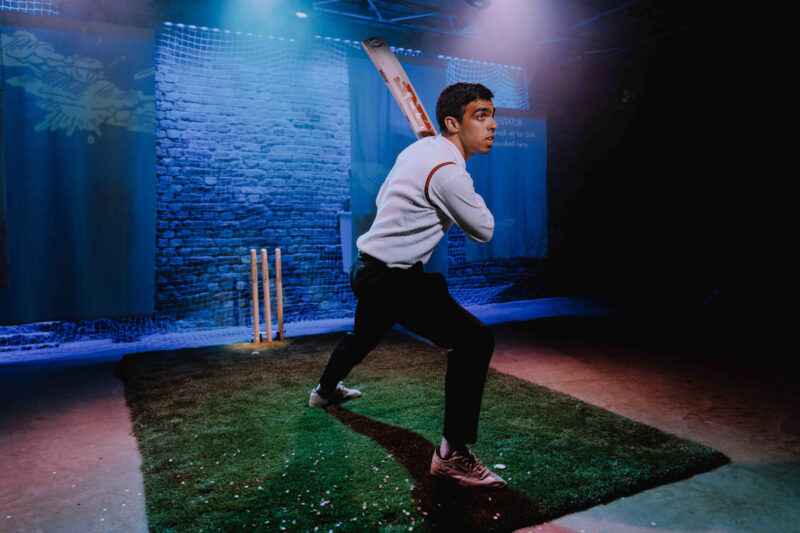

At the other end of the strip, a man with a cricket bat bends his knees and shuffles into position. There’s a satisfying thwock as wood meets leather. The ball then sails past a tall, athletic-looking fielder. By the time he realises what has happened, it’s too late. The batting team has added four runs to its total, setting back an already exhausted opposition.

Watching from the other side of the boundary is Shamim Ahmed, captain of the United Cricket Club (UCC) – a small team of amateur players, mostly in their 30s and 40s, based in north London and founded in 2010. The team, which is funded by whatever spare cash Ahmed and his teammates have left over from their day jobs, is in Division Six of the Middlesex County Cricket League.

Ahmed shrugs sympathetically. The fielder caught off guard has a reasonable excuse. “Maruf has been here since seven in the morning,” he says. “The pitches in the park are first come, first served. We needed someone to come down and save it for us.” Twelve hours later, it’s no wonder he is not on top form.

Thankfully, this is a practice match and its result won’t affect UCC’s position in the 2023 season. Plus, as Ahmed says, it’s not surprising that the players are a little rusty. For some, it’s the first time they have picked up a cricket bat in weeks. They’ve had more time off than usual, owing to Ramadan falling during what would have been pre-season training.

UCC is gearing up for its first match against Northolt Manor. Over the summer, it will compete against 10 sides from across the county. If its players emerge victorious, they will move up in the league, giving them the chance to compete against more established teams and attract sponsors and public funding.

The team may be full of ambition, but just being accepted into the Middlesex County Cricket League was a monumental achievement in itself. For more than a decade, local and regional leagues across London refused UCC entry and, therefore, the right to compete at all.

The problem, Ahmed believes, is not that UCC’s players lack ability. Rather, it’s that the club lacks the necessary funds to secure its own ground. Even though UCC performed beyond anyone’s expectations last season, finishing at the top of its division, it was not promoted and offers to play against more established teams — even for friendly matches — were rejected.

Playing cricket in England can be an expensive pursuit with few publicly available fields in which to play

It’s a challenge that the team continues to face as it is still without a permanent home — a situation that forces its members to train in poorly kept public fields, most of which were never designed with cricket in mind.

Playing cricket in England can be an expensive pursuit. There are few publicly available fields in which to play, while resources such as practice nets are often found only at cricket clubs. Factoring in the cost of equipment — bats, pads and wickets — means that playing even recreationally requires investment.

In Bangladesh, where Ahmed grew up, cricket is a universal passion across all strata of society, and games are played anywhere with the necessary space.

“We would play on the streets, in an unused field — any available space could be turned into a wicket, and there was never a shortage of people looking for a quick hit or a pick-up game,” he says.

In 1990, when Ahmed was 17, he moved from Bangladesh to Camden in north London to study and find work. He lived in a small flat there and discovered that there were few green spaces in which ball games were allowed. Playing in the street, as he did in Bangladesh, was out of the question. Over the years, he reached out to nearby cricket clubs, but found them unwelcoming.

“Some never replied, some said to come for a trial but didn’t give me a date. Even when I did get told where and when to show up, I was never told who I was supposed to meet,” he recalls.

In 2010, Ahmed asked some Bangladeshi, Indian and Sri Lankan friends who lived nearby whether they wanted to get together for a game. One of them, Ashraf, is still part of the club today. “We went to Regent’s Park and I bowled so fast I broke a stump!” he remembers. Those joys turned out to be fleeting, however, when the police intervened, informing the men that playing cricket was not allowed there.

After that, Ahmed and his friends decided to set up their own team, inspired by the improvisation and resourcefulness at the heart of South Asian cricket culture. They had no ground of their own and had to scrimp and save to buy cheap equipment.

“We didn’t even know where to buy stumps!” recalls Ashraf. “We went around so many different shops in Finsbury Park before we could find any equipment — and even when we had it, we couldn’t find many teams to play against.”

To recruit more members, they called on friends and the friends of friends. Ahmed arranged fixtures against South Asian teams based in east London and Essex. In 2018-19, UCC managed one season in a short-lived Essex-based Asian Premier League for teams like theirs that couldn’t find anywhere else to play. UCC finished at the top of their division.

“Then there was a community league in Victoria Park where all the teams were Bangladeshi, and that disappeared too,” Ahmed remembers. “Some of my friends gave up.”

Despite those setbacks, Ahmed persevered, holding training sessions in public parks in north London and covering most of the team’s expenses out of his own pocket. He describes running the club as a “full-time, unpaid job”. Membership also requires sacrifices from his teammates, most of whom work low-paid jobs in the gig economy, such as driving for Uber.

“There were six or seven of us working shifts last night,” Ahmed says, pointing at the other men waiting to bat. “Weekends are when you usually earn most as a cabbie, so I know there are a lot of people who are losing money being here today. That’s the passion we have.”

Despite the obstacles the club faces, it has grown big enough to field two teams: the Saturday league side and a second XI that plays a shorter form of the game on Sundays. It remains a struggle, however, to pool enough money to hire the most basic of facilities, particularly parks and fields on which to host games.

Chronic lack of external funding also means that Ahmed’s other ambition — to extend the amount of community work carried out by UCC — is also under threat of failure. The club uses word-of-mouth and social media platforms to encourage young people to play cricket. Some of its members credit UCC with helping them get off the street or stopping them spending their free time stuck indoors. Despite UCC being formally recognised by the England and Wales Cricket Board, it has been unable to secure grants from local government bodies.

That lack of funding also means that Ahmed can’t afford to start a youth team, which would require paying for mandatory safeguarding courses and investing in equipment for children.

Meanwhile, Ahmed is still fighting to get his team recognised by local cricket leagues. He thought that moment had come in the summer of 2022 when UCC beat their rivals, the Youth Wing, in the final game of that season. The players celebrated exuberantly, assuming that, after their decade-long struggle, the victory would see them promoted. Instead, they were told by the league’s managers that they had not accrued enough points to qualify for promotion.

That’s why Ahmed and his 21 teammates will train on the field until the sun goes down, repeating spin-bowling techniques, perfecting batting strokes and agonising over fielding formations. To him, the evolution of the UCC — from an idea born of childhood memories to a rag-tag team of late-night Uber drivers able to challenge established cricket clubs — has shown cricket’s potential to transform lives. It’s one of the few sports, he believes, where a scrappy, makeshift team from the inner city, where cricket is rarely taught in schools and facilities are few and far between, can go toe-to-toe against better-resourced sides with established histories in the sport, and win.

Newsletter

Newsletter