‘Dabke is a way to keep our culture alive’

The thunderous rhythms and high-energy moves of Palestine and the wider Levant are whipping up a storm at a south London workshop, open to all

On a crisp Saturday afternoon in January, 45 people are stomping their way through a dance routine under an archway in south London. Everyone is hand-in-hand, fingers clasped and shuffling in a curling line to the shrillness of a mijwiz flute, thunderous percussion and soaring Arabic singing. Attendees range from teenagers to middle-aged adults, some have been to the workshop several times before and, for others, it’s their first experience. All are smiling broadly, happy to be moving together.

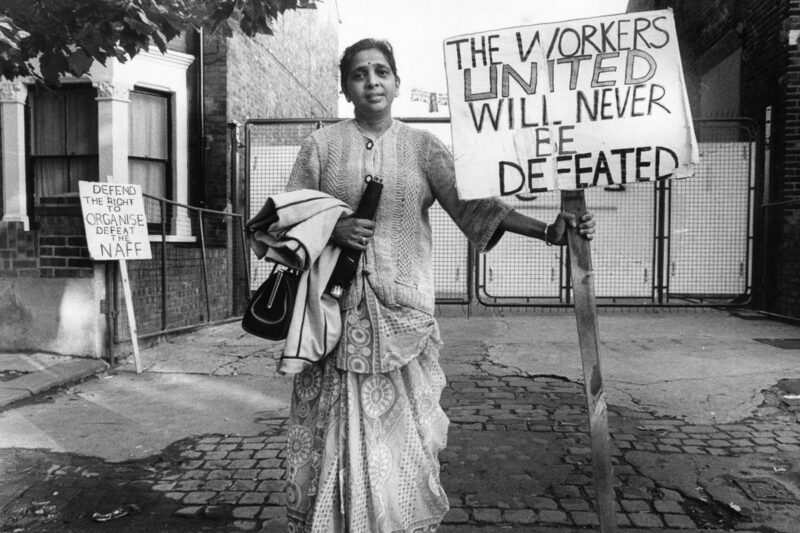

We have gathered to learn the art of dabke. This ancient dance style, with roots in Lebanon, Palestine, Jordan and Syria, is a tradition of both celebration and protest. Its energetic moves are widely believed to have originated from villagers coming together to rhythmically compact the mud roofs of houses with their feet. The dabke of today, which comprises both music and choreography, plays a central role in weddings and festive gatherings. It is also often seen on the streets as a defiant form of performative cultural identity.

“Dabke is an inheritance passed down to generations,” says Omar El-Zeinab, 26, the founder of London-based community workshop DabkeRoots says. “It’s a way for the diaspora to connect with their roots and with each other and it’s also a way to keep our culture alive when so many others are trying to destroy it.”

He organises our group into three lines as instructor Jumana presses play on the Palestinian folk song Mahla Dabkithom. The sound of the mijwiz cuts through the air and, as a rollicking rhythm builds, she teaches us our first six-beat box step sequence. “Feel the rhythm,” she laughs, as people sway side to side, almost losing balance. “Follow the music!”

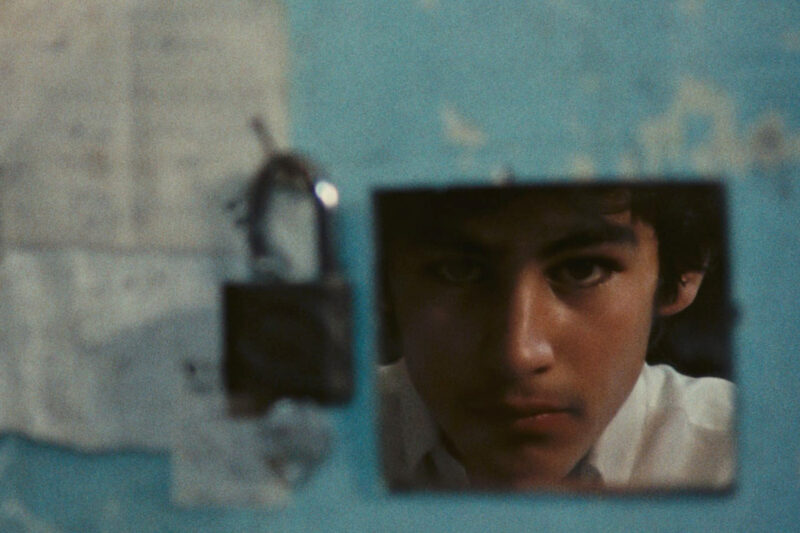

El-Zeinab, 26, was born in London to displaced Palestinian parents and works as a mechanical engineer. When he was 10 years old, his family moved to Lebanon, where he first encountered dabke. “It was such an intrinsic part of the culture. People would dance at celebrations and even after everyday things like eating together,” he says.

“The first time I did it, my friends dragged me into the line and I was so confused, my legs were a shambles. But, once I learned the moves, I found it such a powerful way to connect with my Palestinian identity. Now, when I dance it makes me feel happy and determined to keep teaching others.”

There are many more shambolic legs when our class begins to turn the six-beat box step into a zig-zag from side to side. Nervous laughter erupts as the group lurches from one end of the room to the other. We’re all desperately trying not to crash into one another, but when we reach the end of the sequence everyone bursts into applause and whoops of encouragement. It’s exhilarating to finish our first series of dabke moves.

El-Zeinab returned to London at the age of 15 and continued dancing dabke as a hobby. The events of 7 October 2023 and the subsequent Israeli onslaught against the people of Gaza, however, gave his dancing a new purpose and led him to use his skills to spread awareness of Palestinian culture.

“I went down to the protest encampments at universities like UCL, Soas and King’s and began teaching the people who were staying there dabke,” he says. “They all began teaching each other the moves and it really kept up morale. It also gave them a part of the culture to carry with them. From then on, I knew I needed to start teaching it more widely.”

In October 2024, El-Zeinab started the DabkeRoots Instagram account, which now has more than 5,000 followers. He also began to organise weekly sessions, where people of all backgrounds could congregate and learn. Charging £13 to cover the cost of the room hire and a live drummer, the classes drew a few dozen people.

Eighteen months later, the group’s weekly sessions range from beginners’ classes to an advanced troupe that develops detailed choreography to perform at weddings and parties. Each is attended by around 45 people from a variety of backgrounds and typically has around another 30 on the waiting list. Meanwhile, a members’ WhatsApp community has more than 600 users.

“It’s a joyous thing because some might live here alone, so they send clips of themselves dancing to their families back home,” he says, referring to the significant number of participants from cultures in which dabke is often performed. “The other day I was on a call with someone’s mum and she was so happy to hear I was teaching her son. It’s become a real blessing and privilege to do this.”

Back in our session, we are learning more advanced steps to the Palestinian dabke named Zareef al-Tool, named after a folk song that typically accompanies it. I clasp hands and leap forward with a 46-year-old woman named Stephanie, who tells me that this is her fourth DabkeRoots session.

“I began coming in the autumn. I came across their account on Instagram and thought it would be a fun way to exercise and show solidarity with what’s happening in Palestine right now,” she says. “I’ve also read studies that learning to dance helps your brain and can stop you from getting dementia, so it’s win-win. Every time I’ve come I’ve met different people from all walks of life and learned new moves, it’s great.”

Grabbing my other hand is 26-year-old first-timer Sabir. “I’ve been in the UK for just over a year after moving from India and I’m always looking for new ways to meet people and make friends,” he says. “Today has been a great experience and the moves are simpler than I thought they would be. I’m already planning on sticking around afterwards and getting something to eat with the others.”

Opening up the workshops to people from a diverse range of cultures is key to El-Zeinab’s vision. “Our main priority is always to raise awareness. We’re doing that through collaborations with bhangra groups, public performances and pop-up street shows across London,” he says. “When people walk by and watch us dance, they’re curious to hear what it’s about and we can educate them about Palestinian culture from there. It allows us to all come together.”

In August 2025, DabkeRoots performed in public at the Riverside Terrace, part of London’s Southbank Centre. More than 300 people ended up joining in. One of them was Jumana, today’s instructor.

“I’m half-Algerian, half-Palestinian and learning dabke with DabkeRoots last year felt like such a natural self-expression,” she says. “I first took my mum with me and now I’m a teacher. It’s a joy to spread this amazing energy with others. When we finish a class, everyone is beaming — it’s impossible not to.”

As our session draws to a close, the entire room suddenly breaks into a freestyle dance as the music continues to play. People clap, ululate and drop low on weary knees, while El-Zeinab invites everyone along to a nearby restaurant afterwards to chat and share food.

“We’re connecting through our pain and we’re also celebrating each other,” he says. “We stay for four or five hours sometimes after the sessions, just talking. A lot of people have made great friends here and I hope it continues for a long time to come.”

Newsletter

Newsletter