The power of switching off: how to navigate motherhood in the digital age

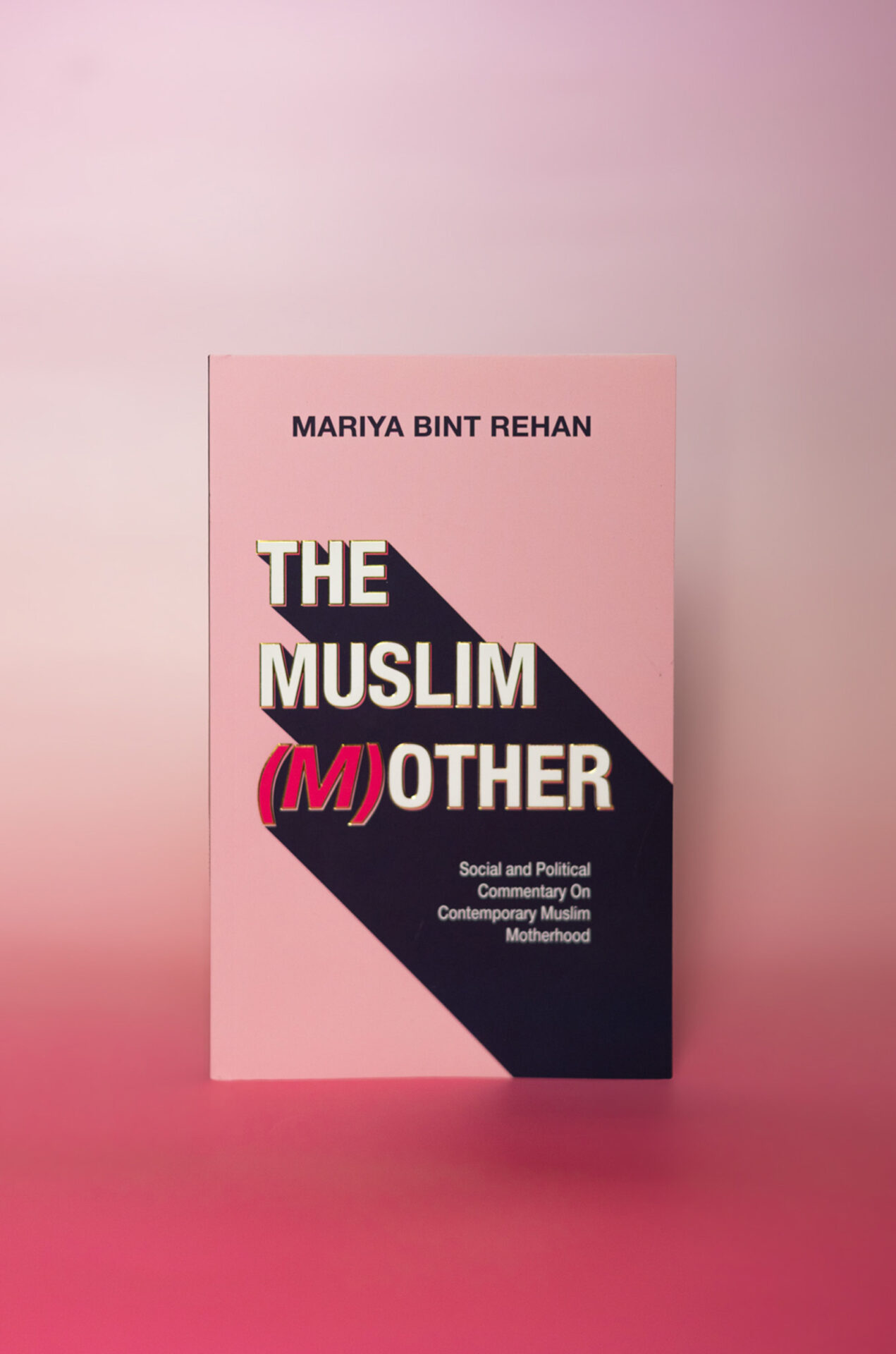

Mariya bint Rehan, the author The Muslim (M)other, speaks to Hyphen about her new book on the experience of parenting

Mothers may be incredibly time-pressed, but we still find moments to scroll through Instagram and TikTok reels — often to our detriment.

Social media offers a plethora of resources on parenting and Islamic learning, but it can also be an anxiety-inducing cesspit of dawah bros offering hot takes on topics they have no authority on, such as being a single mum.

I have often found myself doomscrolling, feeling judged by posts that seem to target me as a Muslim mother — whether it is by non-Muslims who find it strange that I allow my faith to guide the way I parent, or my own community for not being “Islamic enough” in my parenting. So when I came across a new collection of essays by Mariya bint Rehan, The Muslim (M)other: Social and Political Commentary on Contemporary Muslim Motherhood, I felt less isolated.

Rehan is a writer and mother of three from London. Her new book looks at the experience of mothering in the digital age, amid a backdrop of Islamophobia and misogyny.

“The digital world has irreparably changed the way we interact, the way we perceive ourselves and, fundamentally, how we perceive our faith,” she tells me.

Rehan notes that the online world has become a digitised form of mother-and-baby groups, where white mothers see your hijab and make assumptions on how you parent your child as a Muslim — something I experienced myself when my son was a baby. But we also face additional online pressures such as the tradwife movement or the trend of Muslimah girl bosses, who try to convince us that we can “have it all” — a high-paying career and motherhood.

“I write about mothering on a global stage under such intense scrutiny, and I do think there are many untold implications to this on the minds of women who are already paying a high mental tax,” says Rehan. “Muslim mothers are constantly subject to opinion and judgment that centres specifically on their motherhood in a way we have never been before. Our inner peace is being taken over by this monster that seems to be expanding more into everyday life.”

While many essays in The Muslim (M)other delve into the digital world, Rehan also explores how mothers are being affected by social and political movements, such as the rise of the far right and incel ideology.

“I remember my niece coming home from school and singing a playground rhyme about Andrew Tate,” Rehan says. “I just remember thinking, ‘Andrew Tate had gone from being this fringe figure to being ubiquitous enough to be in playground rhymes’. It’s become a monster of its own, because this all affects Muslim mothers, even if we are not digital beings.”

The part of the book that struck me most was how Muslim mothers have become politicised beings, in that our ability to conceive and have children is considered to be a threat by the state. Rehan references Lord Pearson of Rannoch’s statement in July 2024 that Muslim radicals will take over Britain through the “power of their wombs”.

“That political discourse at once reduces Muslim women to this biological function while criticising Islam for apparently doing the same,” says Rehan. “It speaks so much of how Muslim women — and their capacity to mother as central to that — are used as tools in ideological wars.”

This affects the way we parent, as we know that the Islamic practices and beliefs we teach our children at home — from how to pray to why we don’t celebrate other religious festivals — could be perceived by the state as “radicalising” our children through the lens of policies such as Prevent.

“I remember when my daughter was two and someone had bought her a pull-on hijab and she wanted to wear it to the park. My instant reaction was, ‘No, you are not’,” Rehan says.

“I remember asking myself, ‘Where has this feeling come from?’ Because that pull-on hijab is so innocuous outside of the context of the UK — it’s just a cute thing that little Muslim girls wear. We have internalised the Islamophobic gaze when it comes to our children. We have started to perceive them through that lens of suspicion, because that’s how the world perceives our children.”

Rehan offers a solution: “We have to take solace in our faith to deal with it.”

“I think we forget as Muslims that Islam provides us with so much and we just need to lean into it more,” she says. “Our fitrah is our internal validation system, designed by our creator. We need to look into that. Like many things pertaining to our identity as Muslim mothers, I feel like this is an ongoing endeavour. It’s kind of a messy process, but a reassuring one too.”

Even taking a break from the screen — just switching off your phone — can help. It’s something I have found myself trying to do recently, a reminder that the actual parenting takes place offline. In moments like these with my son, playing together in the garden or out for a walk, I am focusing on being present and the anxiety driven by social media and instant messaging apps fades away.

Still, we cannot ignore that we are all part of this digital world and Rehan says she’s far from being a “technology pessimist”. There are many Muslim mothers with large social media followings who are making purposeful content, and the works of child development experts like Canadian physician Dr Gabor Maté are helpful tools. But the internet should be just that — an aid to parenting, not your entire world.

“The internet has been an amazing resource for parenting and the fact that we now have access to such rich understandings of child development means our children are in a good position,” Rehan says. “They have a good basis and a good foundation upon which to build themselves up. We’ve tried to overcome our trauma to help them and, hopefully, that will work.”

The Muslim (M)other by Mariya bint Rehan, published by Kube Publishing, is out on 6 May.

Newsletter

Newsletter