Losing the love of your life to the red pill

A growing number of young Muslim men are being seduced by online antifeminist ideology. Their loved ones face a long struggle to get them back — or having to let go

–

Samayya Khan vividly remembers the moment when, in September, she ended her relationship with Hamza. Her eyes filled with tears as she recalled walking to Edgware Road underground station, the man she had thought was the love of her life yelling at her to come back and telling her that she would be nothing without him. That ugly scene was the culmination of a year of arguments, tearful nights and attempts by Khan to come to terms with Hamza’s rapidly changing personality.

“The last few months of our relationship were just filled with unwinnable arguments,” Khan said. They weren’t the run-of-the-mill disagreements one might expect in any relationship. Even the smallest problems — a restaurant reservation falling through or being late to a date because of heavy traffic — would escalate into shouting matches, often underpinned by Hamza’s increasingly reactionary view of what male and female gender roles should be.

“All he wanted to do was talk about how modern women didn’t have Islamic values any more,” said Khan. “Even when we would spend time together, I’d catch him watching YouTube videos about the evils of feminism on his phone.”

Khan became aware that Hamza (not his real name) was caught up in this world in the last year of their relationship. When she initially saw the videos on his phone, he told her that friends had sent them to him via WhatsApp or that he’d seen them in his recommendations and clicked on them out of curiosity.

What she didn’t realise was the amount he had been watching and the effect they would have on him. When Hamza wasn’t obsessing over the choices of “westernised” Muslim women, he was fixated on other baseless ideas he had encountered online, ranging from who “really” controlled the financial system to British universities encouraging and paying for people to have abortions.

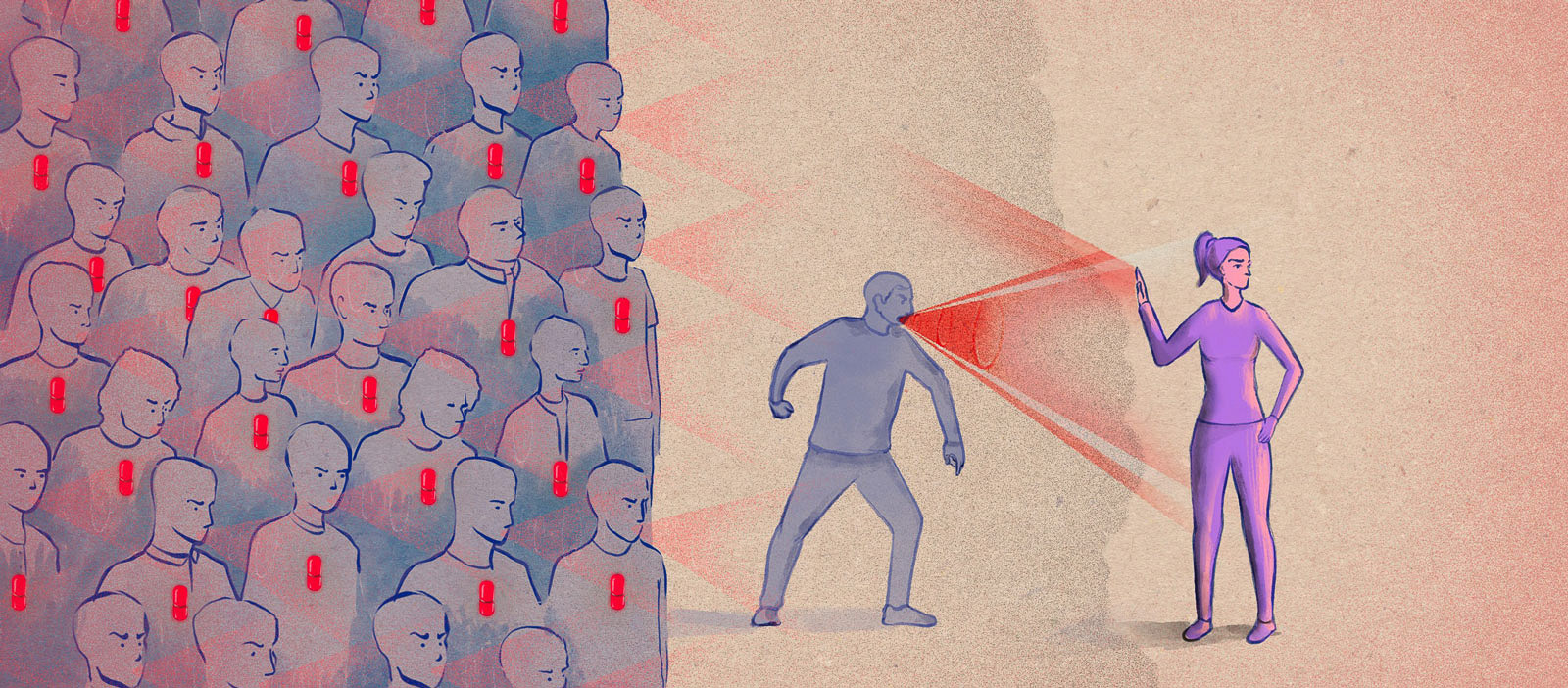

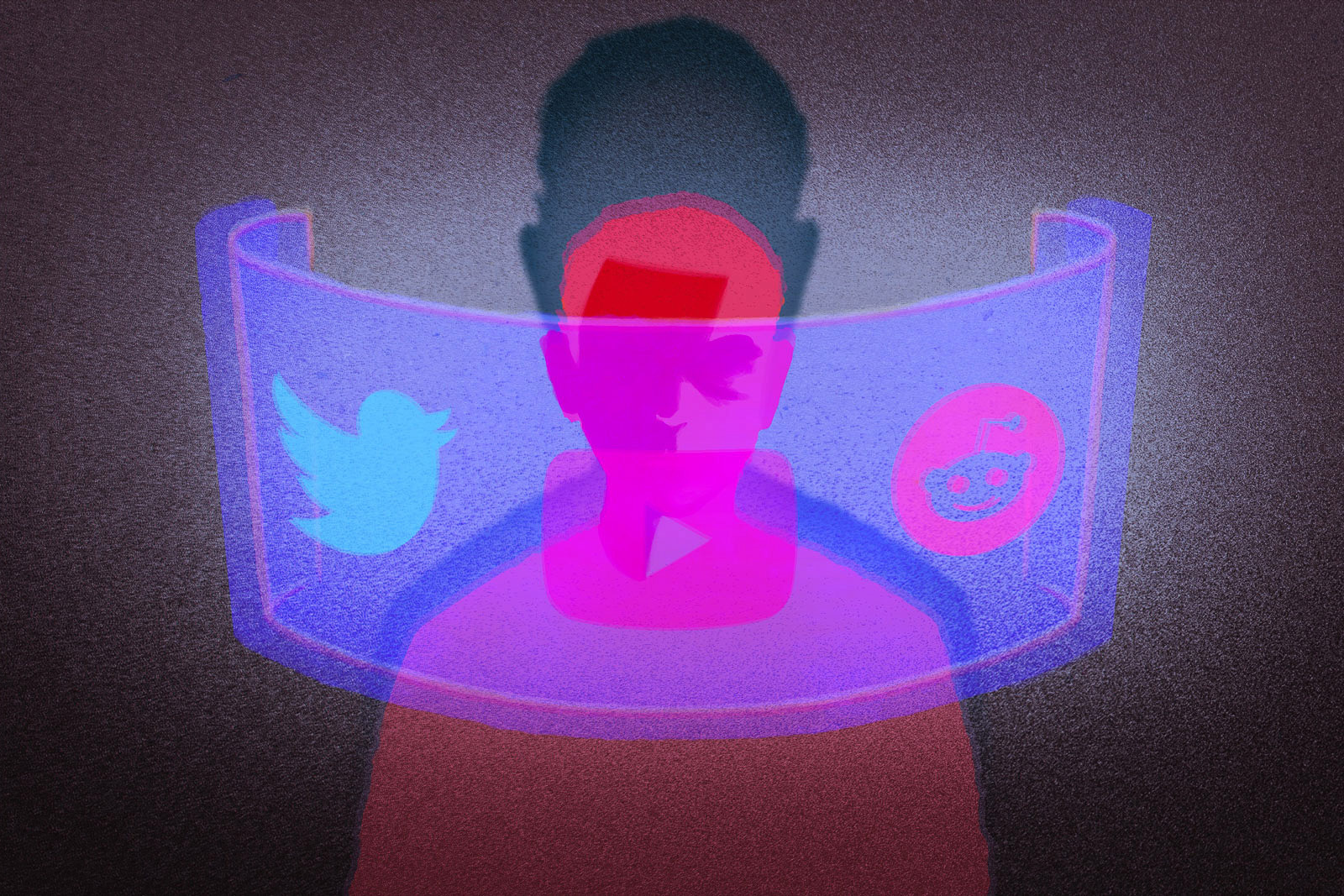

Hamza’s story is a textbook case of “red pilling”: a form of far-right radicalisation in which digital content — including social media posts, streamed video and podcasts — is used to advance dangerous conspiracy theories. The origin of the term lies in the 1999 film The Matrix, in which the protagonist is offered the choice between taking a blue pill or a red one. The blue pill allows him to continue seeing the world just as he always has, while the red one immediately reveals that everything he thought he knew was a comforting illusion concealing a much darker reality.

Dr Annie Kelly is a researcher specialising in conspiracy theories and a co-host of the Manclan podcast, which analyses the world of antifeminist influencers. According to her, far-right social media figures use the term “taking the red pill” to refer to “waking up to the damaging falsity of liberalism, modernity and equality politics”.

While red pill ideology can encompass everything from Islamophobia and antisemitism to anti-vaccine beliefs, misogyny sits at its heart. Immersion in such ideas can prove lethal. The killing of six people in California in 2014 by Elliot Rodger and Alek Minassian’s 2018 truck attack in Toronto, which left 11 people dead, have both been linked to online misogynist movements. Jake Davison, who killed five people in Plymouth in 2021, was also an active participant in various red pill communities.

However, these violent acts represent only a fragment of the wider online subculture. Before its closure, the official Red Pill subreddit had more than 200,000 members and dozens of offshoot communities, including for married men, disabled men and AltRedpill, a community that attempted to apply red pill precepts to non-heterosexual relationships. One of the most popular subreddits was Redpill Islam, where members often criticised Muslim communities in the west for being too soft on issues such as gender segregation, promoting “halal dating” and allowing women to take on leadership roles in mosques.

For much of her two-year relationship with Hamza, Khan had dreamed they would spend the rest of their lives together. Meeting at a friend’s birthday party in 2020, when she was 24 and he was 25, they quickly found that they had both grown up in north-west London and shared similar tastes in music and TV. For Khan, Hamza was a revelation: a down-to-earth guy of a suitable age, with a stable job, a sense of humour and a healthy relationship with his family.

“I’d spent years going on dates that didn’t lead anywhere,” Khan said. “It was hard to find someone who shared my faith but wasn’t demanding that I practise it in a certain way, while also trying to weed out all the men who would pretend to be more religious than they actually were, then eventually send me really disgusting messages.”

Hamza was a practising Muslim and, initially, accepted Khan’s more liberal relationship with Islam. “Religion didn’t even come up much, unless we were trying to figure out what restaurants were halal or not,” she said. While they didn’t live together, they would often take weekend trips to the seaside, attend late-night film screenings and occasionally go out clubbing.

During their best moments together, Khan recalled, it felt like she and Hamza had a strong foundation and a shared sense of priorities. “We were working out our relationship with Islam together, and I really hoped it would end with us getting married, moving into our first little house and having a couple of children,” she said.

But, the more red pill content Hamza consumed, the more distant those hopes became. In the later stages of their relationship, when she and Hamza talked about their future, he dominated the conversation, insisting that they eventually move to a majority-Muslim country to protect their children from the evils of western society.

Red pill dogma is central to a broad online culture known as the “manosphere”: a collection of male-focused internet communities ranging from so-called men’s rights activists to involuntary celibates, or incels. All are bound together by the belief that progressive political movements have waged war against heterosexual men by promoting an aggressive agenda of gender equality, abortion and LGBTQ+ rights.

Following a succession of incel terror attacks around the world, social media platforms now restrict most red pill content. Yet, a simple search online shows that an abundance of adjacent material still cuts through, notably podcasts and TikTok videos that take care not to be too explicit in their terminology, but clearly advance the movement’s central tenets.

The ideology’s popularity is such that earlier this year Andrew Tate, a former kickboxer turned red pill influencer, who has argued that women should be the property of men and that rape victims must bear responsibility for attacks against them, was TikTok’s most popular creator. After considerable public pressure, Tate was banned by TikTok and a range of other platforms in August.

While shutting down the social media accounts of misogynist figures like Tate severely limits their influence, thousands of young men will have already adopted their ideas by the time that step is taken. Khan still struggles to work out when Hamza’s radicalisation began, but she clearly recalls becoming worried by some of the content he started to send her.

“Around the time of the 2021 lockdowns, where Hamza and I were mostly chatting over WhatsApp, he would send me these videos with titles like ‘WAKE UP: FREE YOURSELF FROM THE MATRIX’ and ‘HOW FEMINISM DESTROYS WOMANHOOD’, and ask me what I thought about them,” she said.

“In one of them, a man was talking about how it was a woman’s duty to keep men on a religious path. When I said that men were responsible for themselves, Hamza got incredibly angry, and spent hours talking about how modern women were nothing like the wives of the prophet and his companions.”

Khan also noticed that Hamza was becoming less accepting of the way she chose to observe her faith. “One argument we had was about my friends,” she said. “One of my best friends is gay. Hamza met her at a party we went to and they got on well. But, all of a sudden, he was insistent that I shouldn’t be friends with her, referred to her using awful terms and basically said that her sexuality was one of the reasons I wasn’t practising Islam ‘properly’.”

A recurring theme in red pill philosophy is the conspiracy theory that unseen elites are using Muslim and other immigrants to undermine the status of white, Christian men and deny their “right” to white women and children. Despite this foundation of racism and Islamophobia, Muslim influencers such as Mohammed Hijab have endorsed some of its ideas. Hijab and a number of other popular Muslim influencers were also apparently involved in Tate’s recent conversion to Islam.

If all of that seems counter-intuitive, that’s because it is. However, a 2021 report from the Institute of Strategic Dialogue also shows a close online relationship between the far right and some Salafi extremists, in which the same memes mocking and condemning liberal Muslims, left-wing activists and LGBTQ+ people were shared widely by both groups.

In a recent piece titled “The Rise of the Muslim Incel”, for the online magazine Amaliah, the writer Mariya bint Rehan argues that economic instability, insecurities over Muslim identity in western society and social media algorithms that push a steady stream of increasingly extreme content to users have all contributed to the willingness of some young Muslim men to look past the overt anti-Muslim rhetoric in red pill forums and, instead, view antifeminist and anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment as fertile common ground.

Rehan’s analysis is not dissimilar to that contained in my own book, Follow Me, Akhi: The Online World of British Muslims. Many of my interviewees — men in their 20s and 30s — were happy to ignore the racism and religious prejudice of the manosphere, because they perceived feminism to be a greater peril. As one told me: “The threat of feminism and its role in corrupting Islam is far more dangerous than anything else. In Islam if you see an evil it is your responsibility to fight against it.”

Red pill ideology is no longer the preserve of a select few online initiates. It has well and truly entered the mainstream. No figure embodies this better than Jordan Peterson, a Canadian former psychology professor whose bestselling books and lectures decrying the decline of traditional masculinity have made him a figurehead of the movement.

Some Muslims have attempted to create halal versions of the philosophy, from TikTok trends like #muslimredpill to websites such as Becoming the Alpha Muslim, which provides courses for young Muslim men on how to imitate the “masculine traits” of the companions of the prophet Muhammad. Some Muslim scholars, such as the UK-based Salafi preacher Abu Taymiyyah, have attempted to counter the lure of red pill communities — but not by rejecting their core tenets. Instead, they have argued that “Islam solves most of the problems that the red pill identifies.”

Losing relationships and friendships to red pill radicalisation is not uncommon. However, few people talk about it openly afterwards, not least out of fear of the repercussions, which can include relentless online harassment and the leaking of personal information.

Most of the Muslim women I spoke to for this article did not want to be referred to or identified, but all had similar stories to Khan. Some struggled to maintain romantic relationships when the men in their lives embraced red pill theories. Others had to split up with their partners or call off weddings. One woman has filed to divorce her husband, owing to emotionally abusive behaviour that she believes is firmly rooted in his adoption of antifeminist ideology. Another is desperately trying to rescue her teenage brother from the manosphere.

In the course of her research, Kelly has read hundreds of testimonials on forums and social media groups, written by women struggling to guide their partners out of radicalisation. Those interventions, however, are often unsuccessful.

“People who are in the process of being radicalised online tend to push friends and family away without necessarily realising why or how they’re doing it. That, of course, contributes to their alienation and thus makes the radicalisation more powerful,” she said.

Khan attempted to pull Hamza back several times. She watched some of the videos he recommended in order to understand his point of view and warned his friends about his changing behaviour. Even after their breakup, she sent him messages begging for the “old Hamza” to return. He responded by doubling down on his views and becoming more forthright about them in public.

Khan cut off all contact with Hamza at the beginning of the summer, changing her phone number and deleting her social media accounts. The process has been heartbreaking. During quiet times — commuting from work and going to bed — she finds herself missing the man she fell in love with: “the Hamza with kind eyes and a beautiful smile, who would send me Spotify playlists and get my favourite desserts delivered when I wasn’t feeling great.”

When I asked Khan if she was angry at Hamza, she paused, then said she wasn’t.

“I’m angry at the people who are making money by manipulating people and ruining relationships and aren’t facing any consequences for it,” she said.

Now, Khan is starting to rebuild her life, catching up with friends and going out again. But her past relationship still haunts her. “When I see a happy couple walking down the street now, I can’t help but feel sorry for the woman,” she said. “I just get so scared that this might be one of the last happy moments she remembers, before her partner, her husband, just changes entirely.”

Newsletter

Newsletter