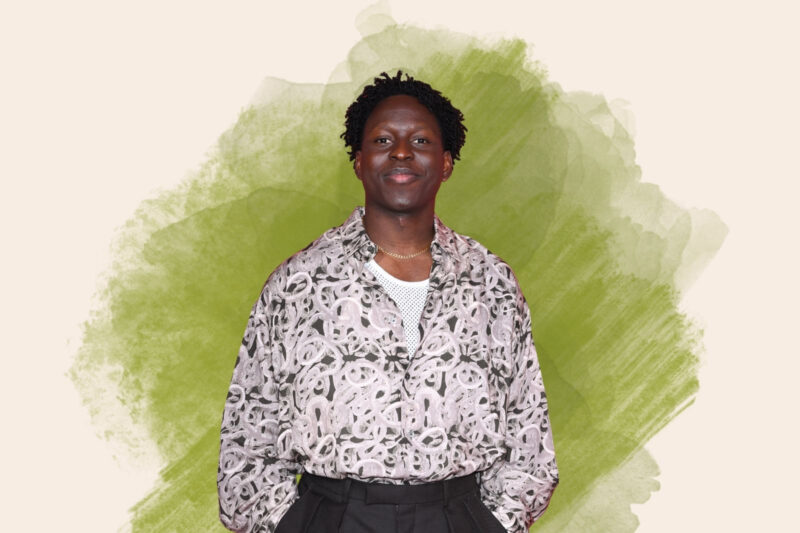

Photographer Mohamed Mohamud captures stories from the worldwide Somali diaspora

It all started as a hobby, shot on an iPhone. Eight years later, 8,000 people in 30 countries have taken part in this globe-spanning project

When I first called Mohamed Mohamud to arrange an interview, he explained it was not the greatest time to chat. “I’m in Indonesia, meeting the Somali community in Jakarta,” he said.

That, in a nutshell, is the award-winning British-Somali photographer and author’s globe-trotting life these days. Mohamud, 31, travels widely for his photographic project, Somali Sideways, aiming to challenge negative stereotypes of the estimated two million-strong Somali diaspora by visiting communities around the world and sharing their experiences.

“I wanted Somali people to be seen and their stories heard,” he tells me when we eventually talk properly, explaining the motivation for an odyssey that began in 2013. So far, he says he’s spoken to 8,000 people in 30 countries on four continents. “The only things that interested people about Somalia were piracy, terrorism and civil war, which I thought distorted our views of it.”

The number of people leaving Somalia grew dramatically following the fall of Siad Barre’s Marxist military regime in 1991. The ensuing civil war substituted a period of dictatorship with statelessness, conflict and exile for hundreds of thousands. The country is still in a fragile state of recovery today.

Between 1990 and 2015, UN estimates suggest the Somali population outside Somalia grew by 136%, or by more than 1 million. At least 80% live in neighbouring Kenya and Ethiopia, but other destinations include Malaysia, Indonesia and Pakistan. There are also large Somali communities across Scandinavia, the UK, Canada and the US. According to 2015 UN figures, 14% of the Somali diaspora live in Europe and about 7% call the US home.

Mohamud’s family left Somalia in the late 1980s, settling in west London, where he grew up. The war was a traumatic experience for many Somali families, says Mohamud, making it difficult for the first generation raised outside the country to embrace their culture. “I didn’t really connect until my later years at university,” he says. “But one of my missions now is to bring these people together by spotlighting their stories, no matter where they are.”

The idea for Somali Sideways started to develop while Mohamud was studying for a bachelor’s degree in international politics at Brunel University, and began as a hobby in the summer of 2015. He kicked off by photographing close friends and other Somalis across London with an iPhone and asking them to tell him about their lives, posting the results on Facebook. “I kept at it and, because the Somali community is tight-knit, news travels fast, so more and more people wanted to have their photo taken and share their story.”

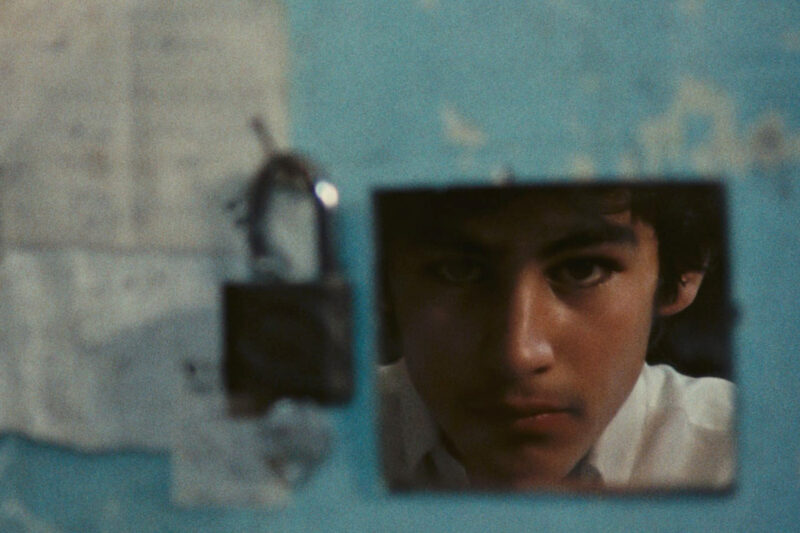

Mohamud’s posts are simple and minimalist, giving you a feel for the characters, but still leaving you curious. Next to each portrait he gives a snippet of text in which the subject shares a memory, a fear, an aspiration or a lingering hope.

The inspiration for the project struck in the final year of Mohamud’s studies in 2013. He wanted to write his thesis on Somalia. After discussing possible research ideas with his supervisor and conducting initial interviews with Somalis living abroad, he noticed there was a stark difference between how they viewed and remembered their country and how it was portrayed in the western media and popular culture. His studies eventually focused on how Somalis viewed media representations of Somalia before and after the civil war.

Ridley Scott’s Black Hawk Down was the first of many films to bring Somalia to western cinema, dramatising a 1993 US special forces operation to capture Mohamed Farrah Aidid, a Somali warlord in Mogadishu. By the end of the mission several hundred Somalis had been killed, as well as 18 US servicemen. The film was criticised for its glorification of US militarism and its unfair portrayal of Somalis. Writing for the New York Times, Elvis Mitchell, a leading American film critic, deplored the movie for depicting Somalis as a “pack of snarling, dark-skinned beasts … intended or not, it reeks of glumly staged racism”.

Several films about the country followed suit, including The Pirates of Somalia and, more recently, Captain Phillips. All lack a “full historical or contextual background” and rarely focus on the resilience of Somalis during the civil war, according to Mohamud.

“It paints a picture that Somalis focus only on anarchy, lawlessness, piracy and terrorism,” he says. “They can simplify nuanced situations, potentially reinforcing negative stereotypes or leaving out crucial information about foreign intervention, colonial legacies, and other factors contributing to the problems in Somalia.”

Mohamud hopes Somali Sideways can bring some balance to coverage of the country and its people. “Entrepreneurs and businesses have reshaped east Africa and there has been a rebirth of arts and culture. I’m showing people some of that.”

The most frequent question he is asked is why the characters he photographs all stand sideways. He explains that it was initially just an aesthetic choice. “I thought it just worked and it was my style,” Mohamud says. During his conversations, however, he noticed that the composition speaks to something else, “that beyond the stereotypes there is another side to every story”.

Mohamud’s work has become a historical and cultural record, charting the development of Somali communities around the world over the past decade. In July 2015, while visiting the US city of Minneapolis, he met Ilhan Omar, who at that point “was just an ambitious Somali woman who wanted to get into national politics”. Omar went on to be the first Somali American elected to Congress, the first woman to wear a hijab on the floor of the House of Representatives, and who is now one of the most widely recognised US lawmakers.

The images and text he has gathered have been collected in two photobooks, the second of which is focused on Somali women and named the Arawello edition, after a queen in Somali folklore.

The success of the project allowed Mohamud to make it his full-time job during the pandemic. In October 2021 he was locked down in Nairobi, Kenya, during a working trip. “Before that I was juggling the project with my job at a bank, but I realised this could go much further if I dedicated myself to it,” he says. He quit that year and never looked back.

The African Union has since recognised Mohamud’s efforts, awarding him a media fellowship along with other African storytellers reframing narratives about the continent, including Algerian journalist Yasmine Bouldjedri and Moroccan broadcaster Meriyem Kokaina.

“It has been a life-changing experience for me to go to all these communities around the world, but we still all have that common connection as Somalis,” he says.

Newsletter

Newsletter