Migrant deaths in Europe reach six-year high

Three months after one of the deadliest migrant shipwrecks in the Mediterranean, little progress has been made in the investigation

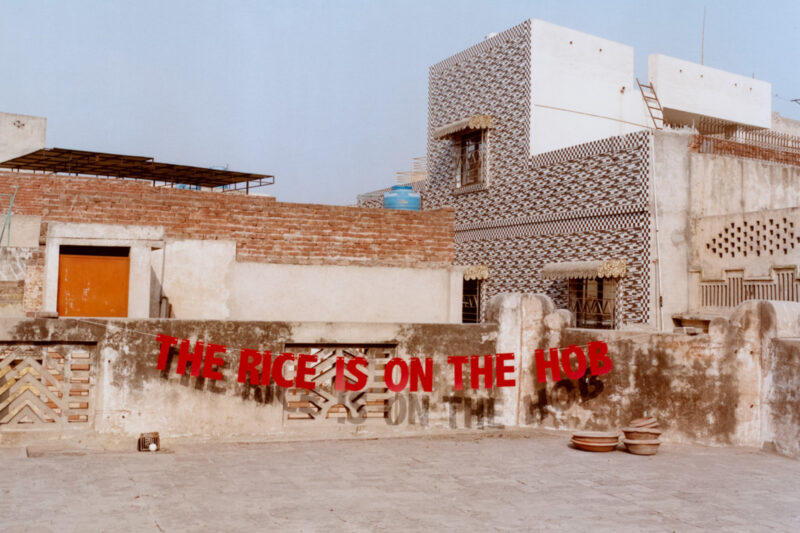

When the smugglers came calling at the Hussein family home in Bhagwal in Pakistan’s Gujrat province, Adel Hussein still had no idea that his brother had drowned in a lethal Mediterranean shipwreck on 14 June.

“The mafia told us that Matlub had arrived safely in Italy and that we must pay the remaining $3,500,” said Adel Hussein. “But I couldn’t get through to him.”

The Hussein family had already paid half the $7,000 (£5,600) demanded by the smugglers so that Matlub and Adel could travel to the East Libyan port of Tobruq. Matlub was chosen over his sibling to board the Adriana, a rusted fishing boat bound for Italy. His brother stayed behind to wait for a second ship.

On 9 June, 700 migrants crammed into the boat, which soon developed engine trouble. Five days later, the Adriana sank off the Greek island of Pylos, taking most of its human cargo into the deepest trench in the Mediterranean. An estimated 510 people died, although Greek authorities have yet to issue a final total.

The Pylos shipwreck marks the latest maritime tragedy at a time of resurgent arrivals and a more confrontational European Union approach to migration. With 2023 hitting a six-year high in both migrant arrivals and deaths, European leaders are increasing efforts to enforce stricter responses to irregular migration, including closer coordination between rightwing governments in Greece and Italy and direct EU political and economic deals with Tunisia and sub-Saharan countries.

The summer fires and floods in Greece have further exacerbated the situation of migrants. The fires in Evros, northeastern Greece, a crossing point used by migrants, claimed at least 20 migrant lives. Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis appeared to blame migrants for the fires on 24 August when he described them as “man-made and manifested along routes used by illegal migrants”.

Migrant deaths at the end of August totalled more than 2,300 of the nearly 160,000 people who entered Europe, according to statistics from the UNHCR, marking a 19% increase on last year. One reason cited for the higher death toll is that migrants are choosing longer and riskier journeys across open seas to avoid detection by Greek authorities.

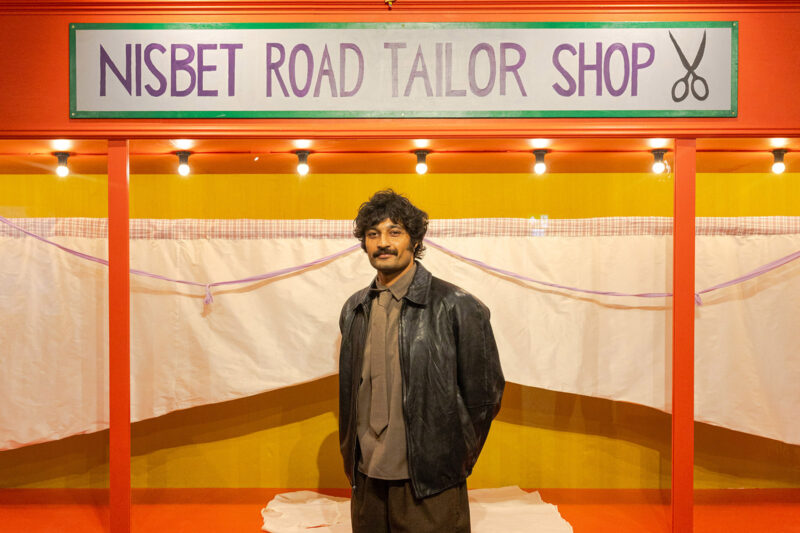

Adel Hussein sits on a bed in a shack shared with four Pakistani workers in a suburban district of Athens. A Pakistani survivor told him that Matlub had come up to the deck to sit with him for several hours at a time but when the Adriana sank, he was in the hold.

The Greek coastguard brought ashore 104 survivors and a further 82 bodies have been retrieved since July. Though the Greek government declared a three-day mourning period, victim testimonies soon emerged claiming that the coastguard — charged with implementing a years-long policy of pushing migrants back on land and at sea — may have been responsible for the disaster.

“The shipwreck happened because the Greek authorities chose not to rescue them but to tow them out of the Greek rescue zone, so that Italy or Malta would have to deal with them,” said Iason Apostolopoulos, a lifeguard activist engaged in rescues on the central Mediterranean migration route. “Their purpose is to prevent them from coming here, even if it’s so they can drown a little further along, in neighbouring waters.”

In July, mobile phones belonging to 20 survivors were discovered on a coastguard patrol boat and handed over to authorities in what is alleged to be an attempted cover-up of potentially crucial evidence relating to the ship’s last moments. Initial claims that the coastguard’s state-of-the-art camera system failed to record the shipwreck were disproved when Greek media broadcast a short coastguard-supplied video shot a few hours before the Adriana’s sinking, showing it keeling dangerously. The video reinforced the coastguard’s narrative that the overloaded ship sank of its own accord.

Those involved with the tragedy accuse the Greek government of criminal negligence. “There’s a mass grave beneath Pylos and it’s incredible that months later the Greek state cannot define how many these people are,” said Thanasis Kampagiannis, a lawyer leading an initiative to sue the Greek state on behalf of the victims’ relatives. “Not only do we still not have a final number of how many are missing, it seems that the Greek state doesn’t want there to be a fixed number.”

Three months after the incident, the Greek police’s Disaster Victim Identification unit has identified “over half” of the 82 bodies retrieved, according to an employee who requested anonymity.

The unit’s forensic experts are mobilised in the wake of large-scale disasters and can identify bodies through DNA testing, fingerprints, dental signs and other unique identifiers.

The victims’ bodies will be buried in Greece after being held in the morgue for a maximum of 40 days to give families time to claim them. Should a DNA match occur following the burial, authorities will allow the bodies to be repatriated to their country of origin.

In Athens, Adel sends £170 of the £600 he earns tending gardens in a wealthy suburb to Matlub’s wife and children. When Matlub’s ten-year-old daughter in Gujrat asks him where her father is, Adel can only say that he has gone off again on another of his journeys. But he is also fighting deportation after the state revoked his residency for declaring a wrong permanent address.

“This residency is mine and my family’s lifeline,” said Adel. “I’m now trying to remain in Greece so I can support my family in Pakistan, and because Pakistan is very corrupt.”

Newsletter

Newsletter