Dženita Karić Q&A: ‘There are so many stories of hajis which I hope to give justice to’

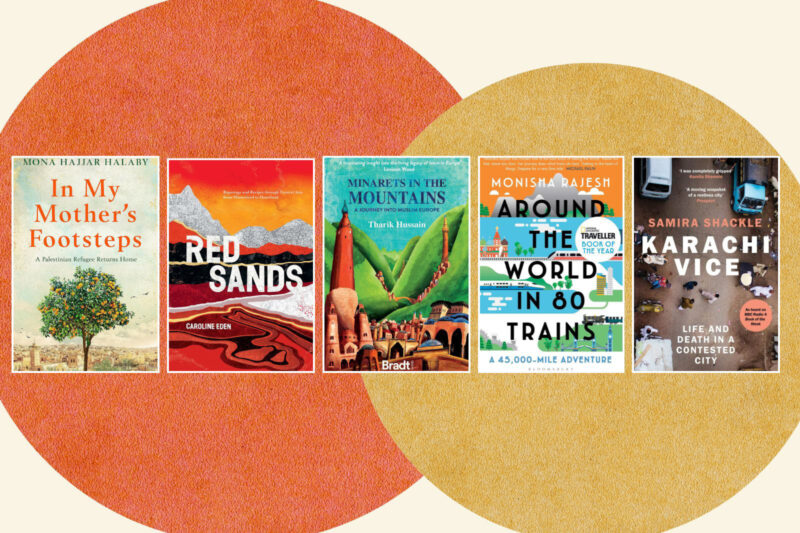

Book cover courtesy of Edinburgh University Press

A new book unearths the extraordinary stories of Hajj recorded by ordinary Bosnians over the past five centuries

Dr Dženita Karić is a senior researcher at the Berlin Institute for Islamic Theology at the Humboldt University of Berlin. She was born and brought up in Sarajevo, Bosnia in the late 1980s, when it was still part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. With the fall of Communism in the 1990s, Yugoslavia fractured and Bosnia declared independence, only to face years of conflict and aggression from Serbia and its supporters.

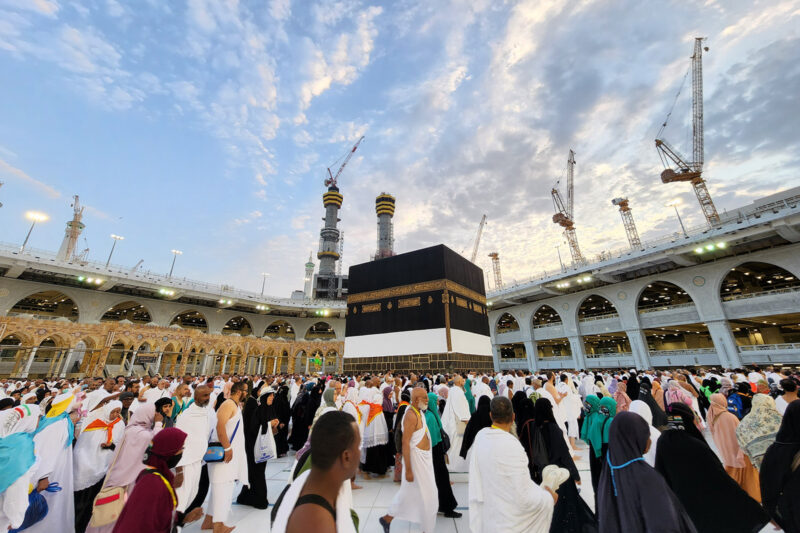

Karić has recently published an incisive book about the history of Hajj literature written by Bosnians over five centuries. In a collection that took more than a decade to research and write, Bosnian Hajj Literature: Multiple Paths to the Holy collects and uncovers stories of Hajj recorded by ordinary Bosnians who detail their experiences of faith and travel to Mecca and Medina. The book also shows how the Hajj often took place against a backdrop of changing political environments, from the communist era, when the pilgrimage was used by the former Yugoslavia to build soft power relationships with Muslim countries, to the war years of the 1990s, when it helped allow a nascent Bosnian state to present itself and its cause to the wider world.

This article has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you start to study the role of Islam in Bosnia?

Bosnia has often been seen as on the periphery of the Islamic world, and I wanted to show that studying Islam in Bosnia can help us understand what religion meant in the pre-modern world and means in the modern world as well. I zoom in on the personal and local dynamics, but I also want to answer some bigger questions.

You’ve written a book about the writings of Bosnians who went on Hajj from the 16th to the 21st century. Why did you think it was important to chronicle this history?

In the 20th and 21st centuries, many ordinary Bosnians who went on Hajj wrote about their experiences and kept travelogues. When they returned home they would make one or two hundred copies of their account and give them out as gifts to friends and family. In the average Muslim home there will be at least two or three of these texts.

In the academic world, nobody really wanted to look into these writings, not even people who dealt with pilgrimage and travel literature, because they were not seen as sophisticated or worthy accounts. I kept coming across this huge body of literature. It made me think about the motivations of the people who wrote them. Why would someone who had never written something in their life decide to write a travelogue? Hajj literature is also a rich source of information on how ordinary people engage with their faith and how the social and political context influences them.

The Bosnian wars of the 1990s threatened to obliterate much of the region’s Islamic history. What is your recollection?

Many religious objects were destroyed because the Serb aggression did not aim only to destroy Bosniak lives but also to destroy Islamic heritage and Islamic culture,” she said. “As a child, I witnessed the destruction of the national and university library and of the Oriental Institute in Sarajevo. For the days after that, I remember seeing the pages of the burned books flying in the air and landing in the backyards of houses.

Tell me how you began researching Hajj literature?

I started with my own family library and networks, and it led me to the libraries. When people found out that I was writing about Hajj literature, they would contact me and say: “My grandfather wrote this. Do you want to look at it?”

I studied in the manuscript libraries in Sarajevo and Istanbul. And I also consulted the manuscripts in Cairo. You can also find so many modern travelogues and reports and writings about Hajj online as well.

The research for your book has taken around a decade. What else did you learn about the relationship between Muslims and Islam?

The research connected me to authors who wrote about Hajj from other parts of the Muslim world. Reading these accounts expanded my view of the huge influence of Hajj on cultures and societies across the world.

It also led me to think about the question of religion in general. My research made me think about what happens to Muslims when they are in environments that are not really conducive to their religious expression, such as conflicts and living in states — like Yugoslavia — that were often hostile towards public expressions of faith. What are these mechanisms which keep people attached to their faith? It’s been a really interesting journey. When I started, I really didn’t know how it would end.

You were able to uncover some amazing stories; which ones are most memorable to you?

There are so many stories of hajis, which I hope to give justice to in my book. On the cover of the book is an illustration of the story of two women who went on Hajj in 1981 by car from Yugoslavia. One was a housewife and the other was a tax accountant. They lived very average lives, and really wanted to go on Hajj by car. Their husbands couldn’t drive so they drove all the way to Mecca, and because they had an international driver’s licence they were able to drive in Saudi too.

They also used the journey to visit Damascus, Ankara and Istanbul, where they looked up relatives who were forced to leave the Balkans at the beginning of the 20th century when the Ottoman Empire collapsed. I was also fascinated by how they would use Yugoslavian socialist slang when talking about Muslims and the Hajj.

Some of the accounts strike me as extremely confessional about the challenges involved in Hajj.

There’s a certain type of honesty, really raw honesty, in these accounts. While many people have really positive experiences that they write about, some people talk about their disappointments, how they did not find what they thought they were looking for spiritually. It’s rare to find that in religious writings.

Every year people go on Hajj, and every year someone else is going to bring back a new story of their experiences. So I don’t feel that the project is finished, even though the book is.

Newsletter

Newsletter