‘Windows to a lost history’: the wonders of Iranian new wave cinema

Between 1964 to 1979 Iranian films were marked by a shared poetic and revolutionary language. Now the Barbican is screening some of the works for the first time in public

Cinema is perhaps Iran’s most celebrated modern art form. Directors such as Abbas Kiarostami, Mohammad Rasoulof and Asghar Farhadi have charmed audiences and film festival juries across the world with tales of gentle humanity cloaked in mystical lyricism. What is less known, largely due to the previously inaccessible nature of many of the films, is how much contemporary directors owe to those of the Iranian new wave.

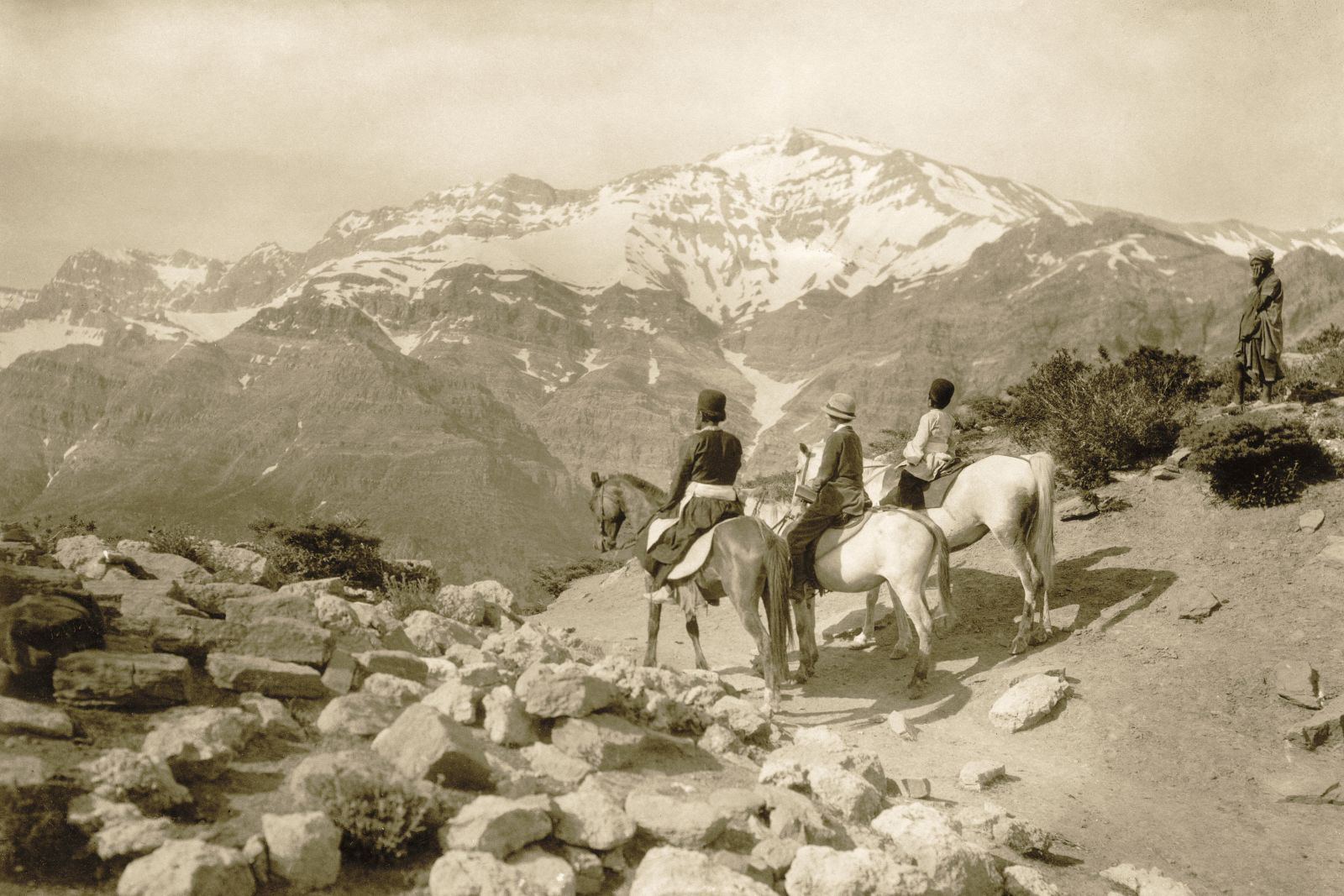

Spanning the period from 1964 to 1979, the films of that era were marked by a shared poetic and often revolutionary language, which blurred the lines between fact and fiction. They explored themes of identity, tradition and modernity against the backdrop of a pre-revolution Iran.

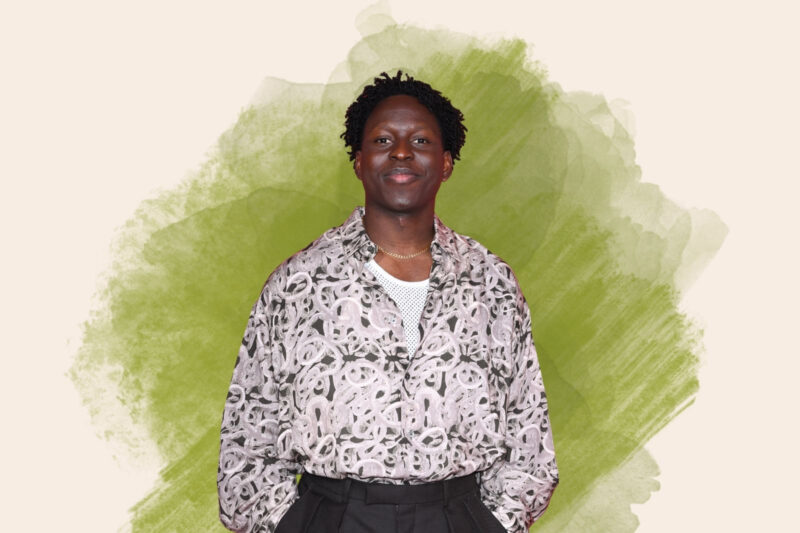

A selection of these films will be shown — some for the first time in public — at the Barbican in London as part of its Masterpieces of the Iranian New Wave series, running from 4-26 February. Curator Ehsan Khoshbakht has spent the past decade diligently working with directors, film archives and rights holders to track down the original elements of these works to preserve and restore them.

“These are the best documents we have of Iran in any art form, because you can see the full documentation of a period: the language, the cities, the attitude, the way they dress, the way they talk,” says Khoshbakht. “It is astonishing that these films exist. They are windows into a completely lost period in the history of our country.”

The Iranian new wave blended realism and symbolism to explore the complexities of society and the human condition. Films such as Dariush Mehrjui’s The Cow (1969), a surreal tale in which the mysterious death a cow in a village drives its owner into poverty and eventual insanity, cemented the movement as a cultural and intellectual force.

Known as cinema-ye-motafavet (alternative cinema), the films were often seen as an antidote to the popular movies of the time, dubbed Filmfarsi by critics. They were defined broadly by their low quality, with what many believed to be weak plots centred around singing and dancing. Filmfarsi was regarded by many Iranians as part of a forced programme of western modernisation being carried out by the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

Much like its French counterpart, which was characterised by a rejection of traditional Hollywood conventions, the Iranian new wave was in many ways a reaction to Filmfarsi’s one-dimensional storytelling. This is particularly true of more radical figures on the scene such as Bahram Beyzaei and Sohrab Shahid Saless.

“Without the popular cinema, we couldn’t have the new wave, but it was not always a clash. It was sometimes an exchange between the two,” says Khoshbakht, noting that some directors purposefully cast major stars of Filmfarsi to tell their revolutionary and countercultural tales.

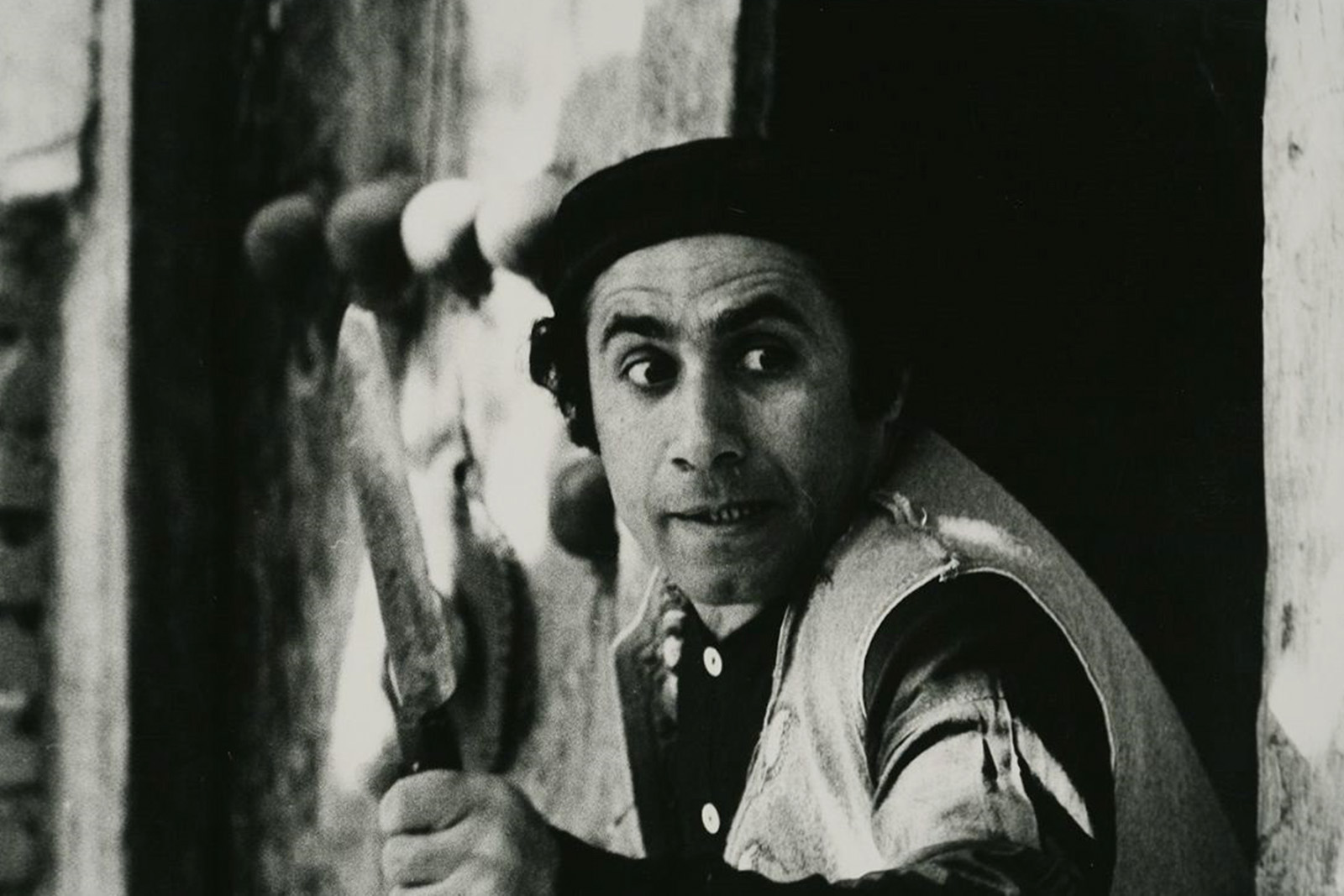

“Ebrahim Golestan wanted to make a very harsh critique of Iranian society, and so he asked Parviz Sayyad — a very popular comedian — and his team, to make the film with them. He deliberately went for the most popular and mainstream [actor] to tell a highly symbolic tale of corruption, tyranny and the nouveau riche,” Khoshbakht says.

Khoshbakht is referring to Golestan’s Secrets of the Jinn Valley Treasure, a “Monty Python-esque allegory about the corrosive impact of oil exports on Iranian life”. The film was banned in Iran two weeks after its 1974 release, and is being screened publicly for the first time as part of the Barbican’s programme.

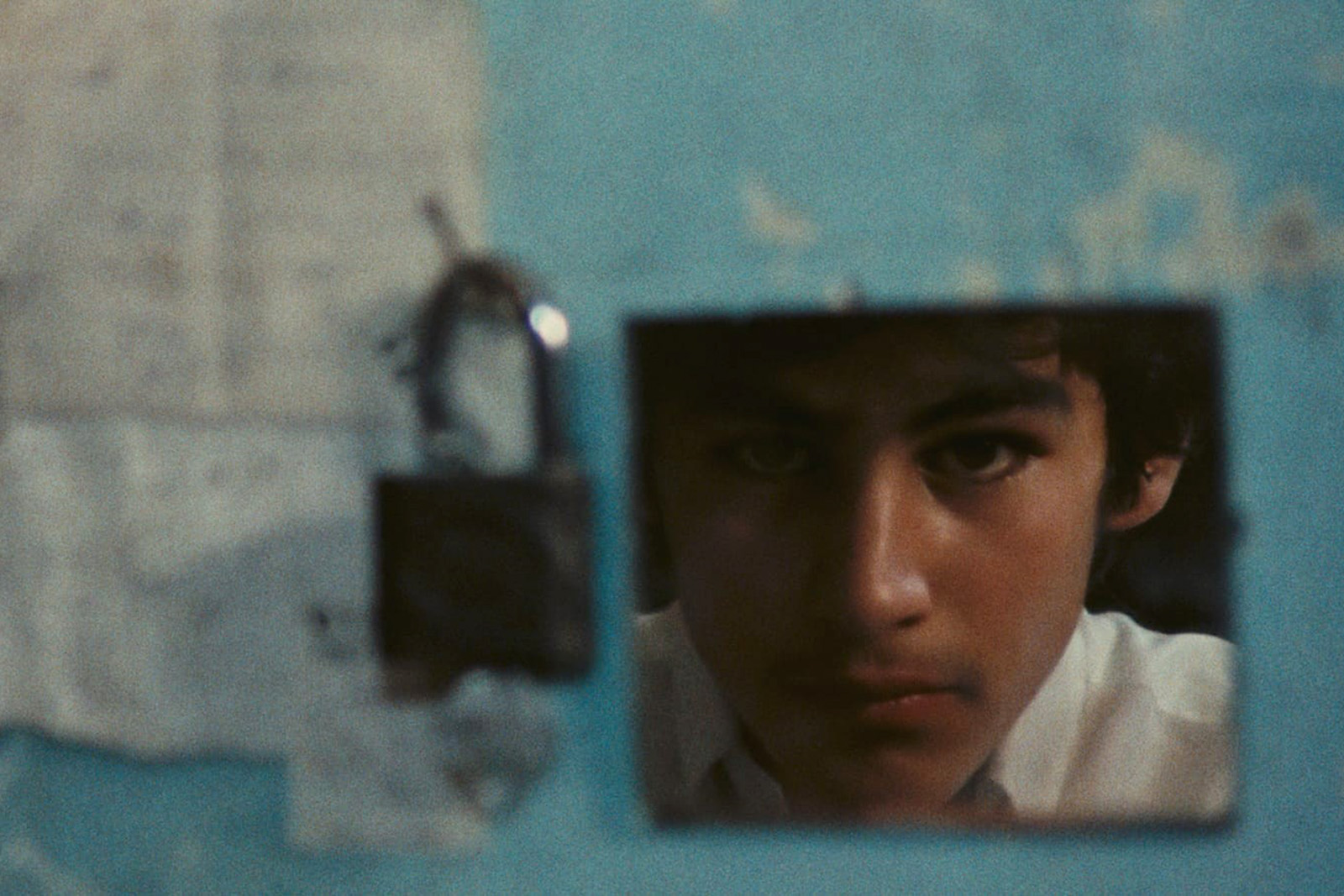

Also showing is Masoud Kimiai’s cult classic The Deer (Gavaznha), which tackles themes of addiction, poverty and redemption through armed struggle. Despite premiering at 1974’s Tehran International Film Festival, it was soon banned for two years and only allowed back into theatres after Kimiai shot a new ending.

“These films also serve as historical records, capturing moments of everyday life, social nuance and collective memory that continue to shape how Iranians understand themselves,” says Homa Rastegar Driver, a trustee of the Iran Heritage Foundation, which helped fund the project as part of its film restoration programme.

“It’s remarkable that, while these films are deeply and specifically Iranian in their cultural details, they are also universal in their soul and scope — easily understood and profoundly felt wherever in the world they are screened,” she says.

Censorship and a fear of the transformative power of art were also features of the Shah’s regime, which ended with the 1979 revolution, much as they are in the Islamic Republic of today.

“Paranoia has been part of Iranian culture for a long time. We’ve been dealing with these contradictions and the limits of freedom of expression since the beginning of the century, and since the early 50s in particular, when there was this fear of the subversive elements of the left and of communists,” says Khoshbakht.

The Iranian new wave is lesser known than the other similar cultural movements of the 60s and 70s, largely due to accessibility — many of the films were hidden away in personal archives in raw formats.

“These films are coming back into the spotlight after a long time, after more than half a century, because of these restoration projects. It’s really a secret treasure,” Khoshbakht adds.

“The restorations reveal the full glory of the work. Details become visible that were not previously apparent, lost sequences are recovered, and director’s cuts — versions that never had the opportunity to reach a wider audience at the time — are finally seen.”

Driver emphasises the importance of showing these films, which reflect the complicated nature of freedom, oppression and national identity, as Iran once again finds itself in a period of significant social and cultural change.

“For those who have not been able to return to Iran since 1979, cinema offers a powerful and accessible way to reconnect with their heritage,” she says. “By restoring and safeguarding these films, we are not only protecting important works of art but also helping to keep cultural memory alive for future generations.”

Masterpieces of the Iranian New Wave is running at the Barbican, London from 4-26 February.

Newsletter

Newsletter