How Muslim dance culture stretches across civilisations

In her new book, historian Nadia Khan uncovers the vibrant, centuries-old traditions of Muslim dance, revealing a hidden history of movement and faith

Author and cultural historian Nadia Khan can still recall the moment dance first moved her. She was nine, attending a Muslim Women’s Day community event organised by her mother in Wembley, north-west London, when she saw a Moroccan mother and daughter performing the shikhat, a traditional belly dance.

“They moved so elegantly, in ways I didn’t know were physically possible. I think I fell in love with dance. I thought it looked so beautiful and graceful,” Khan says.

The performance opened her eyes to the possibilities of dance across Muslim lands, and so began her lifelong curiosity.

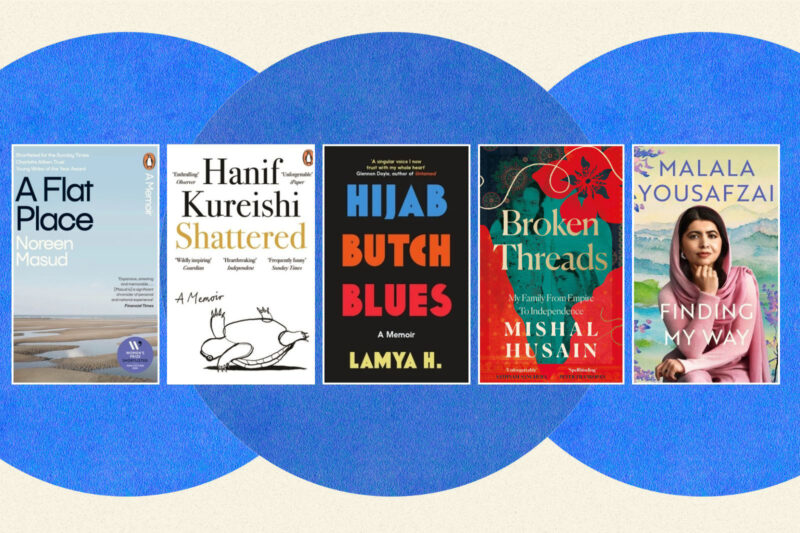

Her book, Dance Histories: A Journey Across the Muslim Silk Road, is an attempt to map a vast, undocumented terrain of dance traditions stretching across parts of the Muslim world.

“Movement has always been part of Muslims’ spiritual, communal and emotional vocabulary, and the only reason these histories feel invisible is because they were lived, not archived,” Khan says.

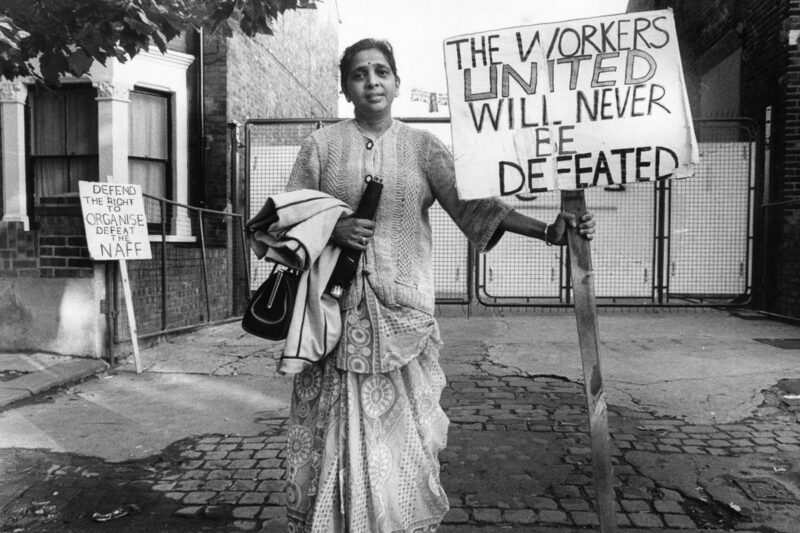

In some Muslim communities, dancing in public or mixed settings was discouraged, not because Islam bans it (the Qur’an does not) but because women’s bodies in motion were thought to draw the male gaze and risk fitna.

“The discomfort lies not in movement itself, but in the unsolicited gaze upon it, when dance is interpreted through colonial, patriarchal or commercial lenses,” says Khan. “An eagle dance or village folk performance carries profoundly different meaning than a nightclub show.” These distinctions are central in Islamic ethics, where intention and environment shape the moral framework of any act.

This nuance is widely misunderstood and under-researched. “Much of what is written about Muslim women and dance comes through orientalist tropes rather than Muslim voices themselves,” Khan adds. “I wanted to write this book to fill that gap, to show that women’s movement, when rooted in spirituality, culture and community, is not an act of rebellion, but entirely within the fold of Islam.”

Her book highlights dances that challenge assumptions about who moves in Muslim cultures. Through her writings we learn about the eagle dance in Tajikistan, mimicking the golden eagle. Men perform it with vigour, women with grace, yet both embody the same natural spirit. “It shows how fluid these traditions really are,” Khan says.

Then there’s singkil, the dance of the southern Philippines, reminding readers that Muslim communities maintain folk dances rooted in ritual and communal celebration, often overlooked in global narratives. “These dances are vibrant, complex and entirely part of Muslim cultural life,” she explains.

She also features Fahima Mirzaei, one of the few women who perform the sema, the whirling Sufi practice often viewed as male-only. “People don’t realise women have whirled for centuries,” Khan notes. “Fahima represents women reclaiming sacred movement with dignity. These stories were essential. Women have always danced across Muslim worlds; the missing piece was the record.”

Khan shows how dance has pulsed through public life across Muslim cultures: wedding lines twisting through courtyards, communal dances marking the change of seasons, and the grounded power of dabke. Some say the latter dance form began on the rooftops of Levantine homes, when neighbours would gather to tamp down and repair a family’s wet mud roof, pressing their collective strength into the earth above them.

It’s details like this that Khan captures so carefully in a book that is part cultural history, part travelogue, part memoir.

She moves effortlessly between scholarship and personal memory, blending meticulous research with lived experience and stories she has gathered from dancers across the Muslim world.

Dance has always been a part of Khan’s life. She grew up in a British Indo-Pakistani household and recalls her mother telling her stories of the Pakistan Arts Academy who would rehearse in her grandparents’ living room on their UK visits. The troupe was founded in 1966 by Pakistan International Airlines and led for a decade by the legendary performer Zia Mohyeddin.

For Khan, physical movement was natural in all women’s settings, passed down through henna nights, kitchen discos, women-only halls and improvised dancefloors fashioned from tabletops and tiled living rooms.

She began to research dance five years ago, digging through the limited academic work that existed: online journals, obscure PhD theses and hours in the quiet corners of Soas University of London’s library. It was there she followed the threads laid by ethnomusicologist Lois Ibsen Al-Faruqi, whose early scholarship first proposed that a Muslim dance culture stretched across civilisations.

Across her interviews, a pattern emerged: the archive of dance and physical movement had been severed or sanitised.

“Dancers in the book said that they didn’t know that the dance form they practised had Islamic history and symbolism,” she explains. “They had been sold a nationalistic version which erased the Muslim history… Islam didn’t suit that narrative.”

One example that particularly struck her was the work of Diana Takutdinova, a Tatar scholar and dance researcher whose PhD explores Islamic reflections in Tatar folk dance. “There isn’t much awareness of Tatar Muslims and their long history of being indigenous to Europe,” Khan says.

Takutdinova told her that finding academic research connecting Islam in Russia to dance traditions was almost impossible. But, through interviews with local communities and close observation of folk performances, “she could clearly see a Muslim influence in how the dances were performed.” The world-renowned ballet dancer Rudolf Nureyev also had Tatar Muslim roots, something he spoke about in later years.

Khan makes clear that dance is foundational to Islamic life. “When you feel, you dance,” she says. It’s in the rhythmic swaying of mawlid gatherings or the meditative rotations of Sufi whirling, from impromptu dance-offs when preparing meals to the celebratory dance circles people break into upon hearing good news.

For Khan, the conversation always comes back to intention, a central principle in Islam. “Are you moving to let off steam? To celebrate? To express gratitude? Intention shapes everything in our faith, and dance is no different.”

She doesn’t worry about criticism from traditionalists. “If the intention is reconnecting with beauty, how can that be shameful? The Prophet said Allah is beautiful and loves beauty. Movement is part of that beauty.”

Dance Histories: A Journey Across the Muslim Silk Road is published by Beacon Books.

Newsletter

Newsletter