Inquest finds Black Muslim woman died after missed opportunities in care

Ayaan Ali Waeys died of natural causes, coroner concludes, but says medics had chances to ‘change course of events’

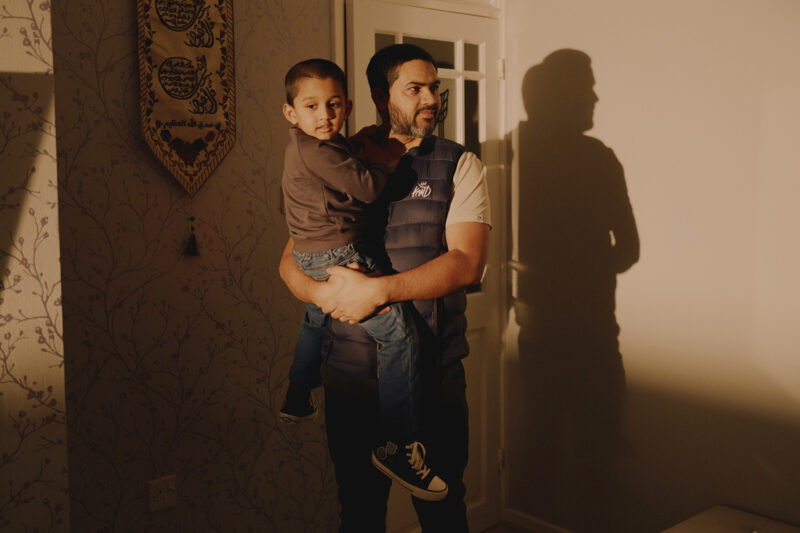

The family of Ayaan Ali Waeys, a Black Muslim woman who died after giving birth to a stillborn baby at a London hospital, have called for urgent action to address racial inequalities in maternity services, after a coroner identified missed opportunities in her care.

Waeys, 35, died on 16 November 2022 from a catastrophic brain haemorrhage linked to fulminating pre-eclamptic toxaemia — a severe form of pre-eclampsia — two weeks after the stillbirth of her first child, a daughter named Nusaiba, at Guy’s and St Thomas’ hospital.

Delivering her conclusion on Tuesday following the inquest at London Inner South coroner’s court, assistant coroner Liliane Field found that Waeys received “suboptimal” care at the hospital, including a four-and-a-half-hour wait for an intensive care bed, but said there was insufficient evidence to conclude that earlier intervention would have prevented her death.

Speaking outside the court, Firdous Ibrahim, a senior associate solicitor in the medical negligence department at Leigh Day who represented the family, said that although the inquest did not examine Waeys’ identity as a Black Muslim woman as a possible factor in her care, it remained an important issue. “We recognise that wasn’t within the coroner’s scope of the inquest, but we often hear about these statistics, and pre-eclampsia and gestational diabetes are more common in women from ethnic minority backgrounds,” she said.

“That definitely did play into the background and we hope, with the family’s permission, that this is a case that we would continue to present to fight for that ongoing urgent action that is needed to address these inequalities in healthcare.”

Waeys’ sister, Fowsiyo Ali Waeys, said the family continues to “feel the deep pain” of Waeys and Nusaiba’s absence every day. “While nothing can ease the heartbreak and loss, we hope that the coroner’s consideration into preventing future deaths will lead to meaningful change in maternity care. Our wish is that lessons are learned so that no other family has to endure the same tragedy,” she said.

The family have long argued that race and bias influenced how Waeys was treated, and that her case reflects broader inequalities in maternity care for Black women. Fowsiyo Ali Waeys said the family may have been treated differently because of their race and religion, noting that doctors sometimes appeared surprised when she, rather than the men she was with, led questions about her sister’s care.

In her narrative conclusion, the coroner highlighted missed opportunities including a test result four days before the stillbirth showing a raised protein creatinine ratio, an indicator of pre-eclampsia. She said this should have triggered an escalation of care, including discussion with a consultant obstetrician and possible hospital admission. “This was a tangible opportunity to bring forward Ayaan’s delivery before… the catastrophic events that followed,” Field said.

Field also added that even if Waeys had not been admitted following another check-up on 1 November, she should have been admitted on the morning of 2 November, the day she ended up giving birth, where she would have received regular blood pressure checks and monitoring of her baby’s heart rate. “This was another tangible opportunity to change the course of events,” she said, but noted it was not possible to conclude that this would have changed the outcome for Waeys or her daughter.

The coroner held that the only conclusion available would be that Waeys died of natural causes, described as “the normal progression of a natural illness or disease, which runs its full course and results in death, without any significant human intervention”, but added that this “does not mean that there was no fault”.

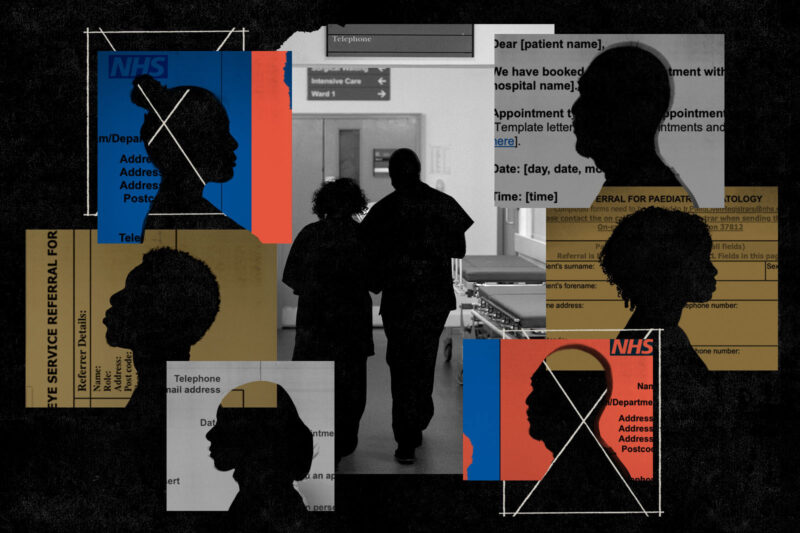

A spokesperson for Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust said: “The deaths of Ayaan and her daughter were a tragedy, and her family have our heartfelt sympathies.” They added: “Where the coroner has identified areas for improvement, we are very sorry for the additional distress this caused and are already taking action.”

They also “strongly” denied that racism or discrimination had played a part in the family’s treatment.

Field concluded that the trust had taken a number of steps to improve care since Waeys’ death, including increasing midwifery staffing levels in the maternity assessment unit and introducing an electronic patient record system to flag blood test results more quickly. However, she said there remained a “large gap” as she had not received any action plan regarding pressure on intensive care beds. She described the waiting time as “almost unheard of” and the “competition for beds” that night a “perfect storm”.

The conclusion comes amid wider concerns over racial disparities in maternity care in England. An independent investigation by the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch (HSIB) following Waeys’ death highlighted that Black, Asian and minority ethnic mothers are at higher risk of complications, with Black women almost four times more likely to die during pregnancy or childbirth than white women. HSIB also noted that stillbirth and neonatal mortality rates rise with deprivation and disproportionately affect babies from Black and South Asian backgrounds.

Newsletter

Newsletter