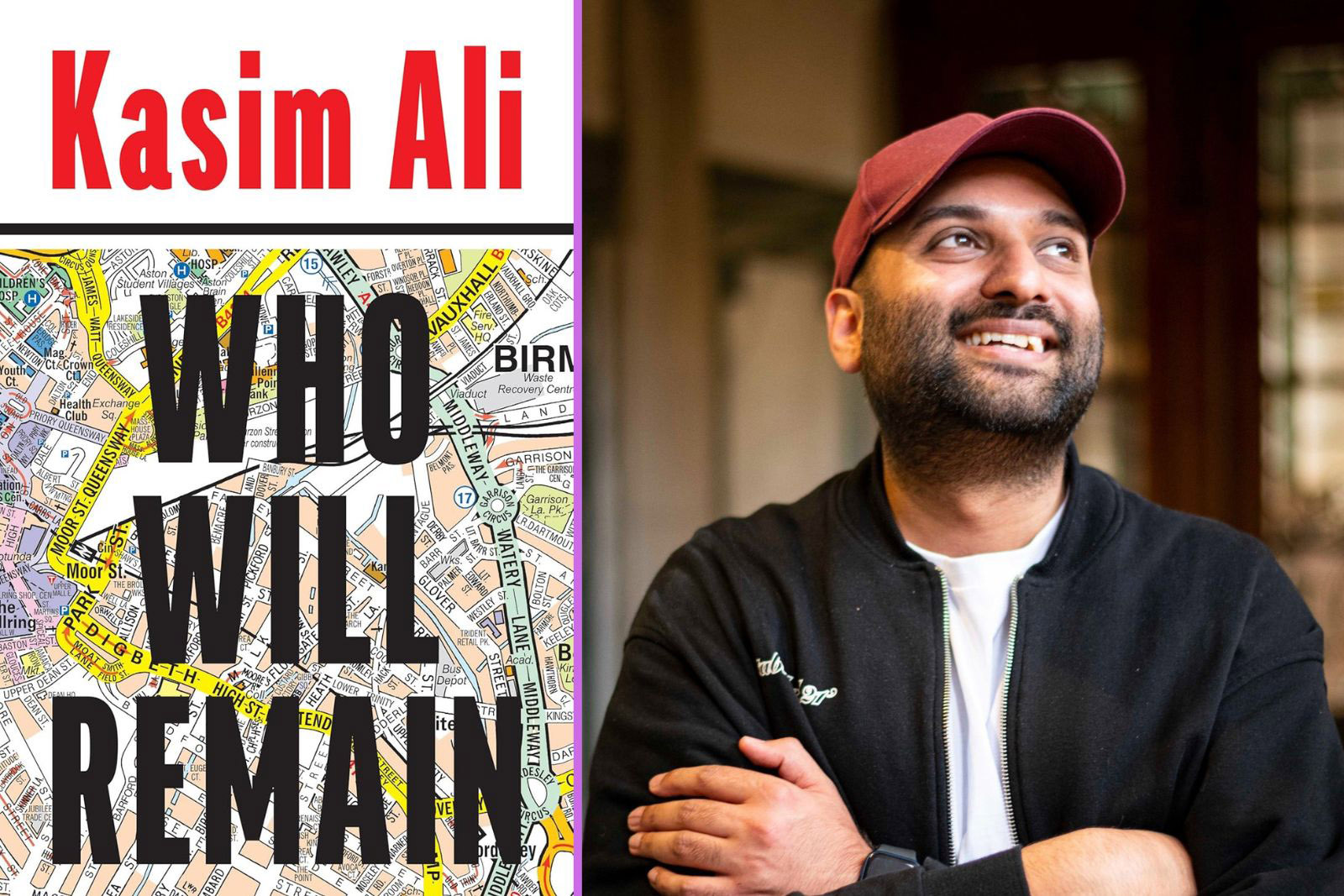

Kasim Ali: ‘Some men think that shifting to the right is what’s going to save them’

The author talks about his hometown and the themes of contemporary masculinity that run through his second novel Who Will Remain

When Birmingham-born author Kasim Ali, 30, first appeared on the literary scene three years ago, it was with the news that his first novel had been snapped up by the publisher 4th Estate in a two-book, six-figure deal. His acclaimed debut, Good Intentions, focuses on a young man hiding an interracial relationship from his parents, unable to choose between familial obligation and the future he truly wants. It also explores shame, mental health and anti-Black prejudice within the UK Pakistani community.

Ali’s new novel, Who Will Remain, is just as bold, telling the story of 20-year-old Amir, a Pakistani Muslim man from Birmingham, whose cousin is stabbed to death at the start of the narrative. That tragic event, Ali explains, “makes Amir reconsider a lot of things in his life. He starts making some terrible decisions about money, power and responsibility in an attempt to control things that I don’t think can be controlled”.

The book opens a window to the lives of British Pakistanis and takes a searching look at what it means to be a man today. Here, he talks about what it means to him.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Congratulations on the publication of Who Will Remain. You’re a prolific writer, with several unpublished novels already written. When did you get the idea for this one and why has it become your second novel?

I actually wrote what I thought was going to be my second novel before the first one had been published. Because I work in the industry, I know that a lot of authors find second books difficult. Suddenly, there’s a perceived readership. Reviews. Expectations.

I thought, “I’ll skip all of that and write it before the first one comes out. Perfect. Sorted.” But when the paperback of Good Intentions came out, I had this crisis. I realised that I had written the second book when I was a completely different person. It wasn’t doing what I wanted it to do. I thought about how I wanted to write about people where I come from — young men specifically — and the pressures they face. Young women are published in literary fiction constantly and there’s nothing wrong with that, but I’m not seeing the same space given to young men. So, I started the second novel again.

I’m particularly interested in the setting of the novel. Birmingham’s Alum Rock neighbourhood is known for its food and desi clothes shops, but others see it as a crime-ridden no-go zone, where Muslims live parallel lives to the rest of Britain. Why did you set the book there?

The simple answer is, I was born there. It was only when I left Alum Rock for university that I realised how people looked down on it. As a kid, all I remember is the family members who had left coming back. They missed this clothes shop and needed that kind of food. They missed their family, the sense of community. The Alum Rock I grew up in was super-safe, almost like a panopticon, with people looking in on you. On that road someone always knows your mum, your dad. You’re not getting away with anything and there was a real sense of safety, community and love.

Many people will recognise that community because it’s so similar to other Pakistani Muslim areas in the country. The novel also centres on the involvement of young Pakistani men in the drug trade. What made you write about this?

This is a complicated conversation, which people oversimplify. The general narrative is that the people who sell drugs are bad people. They’re doing it for bad reasons and they should get regular jobs, like the rest of us. When I was growing up in Alum Rock, yes, people sold drugs and, yes, my parents warned me against that. I also spent a lot of my youth looking at the people who sold drugs thinking, “Oh, I want some of that money. If only I didn’t have to sell drugs and be threatened with violence to get that.”

I wanted to explore not only why someone might make that choice, in terms of getting money, power and feeling more in control of their lives, but also that some people do it because it’s the only way they can access money and afford to pay for things. There are so many factors that go into the decision, especially in places that have been abandoned by the local government. Budgets are being slashed all the time. You don’t have support for people and then you expect them to pull themselves out of these situations by themselves.

Through Amir you explore many of the challenges of contemporary masculinity. Why do you think it’s important for us to talk about that right now, both within the Pakistani Muslim community and more broadly?

I would say that men — straight men specifically — don’t know what to do with themselves any more. I have a cousin who, growing up, seemed to share my beliefs in socialism and human rights for all, but now he’s talking about women having too much and how trans and gay people shouldn’t exist. He has very capitalist ideas about how to make money and build a life. He keeps talking about wanting generational wealth. If I take a step back, I can see him looking at his father, who’s worked all his life and has nothing to show for it. My cousin doesn’t want that.

But when I look at his ideas about women and LGBTQI+ people, I see how it’s about his position in society. You were at the top, but now you’re surrounded by women in your family who have better degrees than you and careers that earn more money. You didn’t work so hard because you thought that things should be given to you, because you’re a man.

I’m generalising here, but I’m thinking about the young men I’ve been in contact with and the ones I’ve left behind in Alum Rock. It’s as if they believe the only choice they can make is to go rightwards, to become harder, sharper, to embrace conservative beliefs, thinking that’s what’s going to save them. But all it’s doing is isolating them and making them really hard to spend time with.

Were you thinking at all about the radicalisation of young men online when you were writing this book?

In an earlier version, yes. I wanted to think about online spaces, but I realised that was a different book from the one I was writing. And, actually, the focus on the online stuff maybe detracts from what’s happening elsewhere. Yes, there’s rabid misogyny and incel behaviour online, but this kind of regressive ideology exists in ordinary spaces too. When I look at my female friends who are in relationships with men, or at the men in my community who are married to women, there are a lot of regressive beliefs about women. It’s happening everywhere. That’s why I decided to write about someone who does not have an internet presence in the book.

What did you want the novel to say about what it’s like to be a man today?

I wanted to show a young man who isn’t affected by just one thing. It’s not just his family, romantic relationships, friends or education. It’s not just his cousin being killed or his brother getting engaged. All these things are happening at the same time. Young men feel that quite a lot these days — that a lot of things, across the board, are happening to them that make it hard to simply exist.

Despite the world he lives in, Amir is quite gentle and sensitive. You seem drawn to that kind of character. Why?

Every man I’ve ever known well has been that kind of man. They feel very strongly. It’s the way they inhabit their emotions that is different. The men I grew up with, everything was led by feeling. You could talk to them and they would tell you they were acting logically, but when you look back at it, everything was led by the heart. That’s the kind of person I am too.

The relationships between the men in your book are really interesting. I’m thinking about Amir and his brother Bilal and his uncle, but also Amir and his university friends. There’s more care and tenderness in the relationships between brown men than is generally acknowledged.

Isn’t it fascinating? This is how Pakistani men behave. I have been to Pakistan a handful of times and I’ve always been really struck by how men act around one another. They’re sitting very closely, giving each other hugs. They’re complimenting each other’s appearance without the terror of being seen as gay. It’s weird to me, that dichotomy between what happens in Pakistan and what happens when Pakistanis settle in Britain.

Yes, I’m also fascinated by how British culture affects the kinds of men we think we’re allowed to be. Finally, what are your hopes for this book?

I really hope that some people from Alum Rock read it. Young men, young South Asian Muslim men, especially, including my younger brother. I want to show them that literature is a space for them too. I’m not saying that I’m the messiah for South Asian Muslim men, but I have an opportunity here to provide them with a space that was not provided to me when I was younger. I want to say: “Maybe this is something you want to do. Maybe this is something you could do.”

Who Will Remain by Kasim Ali is published by 4th Estate.

Newsletter

Newsletter