The National Trust is exploring its Islamic history

The heritage organisation has embarked upon a new project to rediscover and understand the stories of artefacts from around the Muslim world

In 1818 John Barker was stationed in the city of Aleppo as consul for the Levant Company, which was chartered by the crown to manage trade with the Ottoman Empire. During his time in the ancient commercial hub, which now lies in the north of modern-day Syria, he sought out books and other artefacts that would appeal to his friends back home in England.

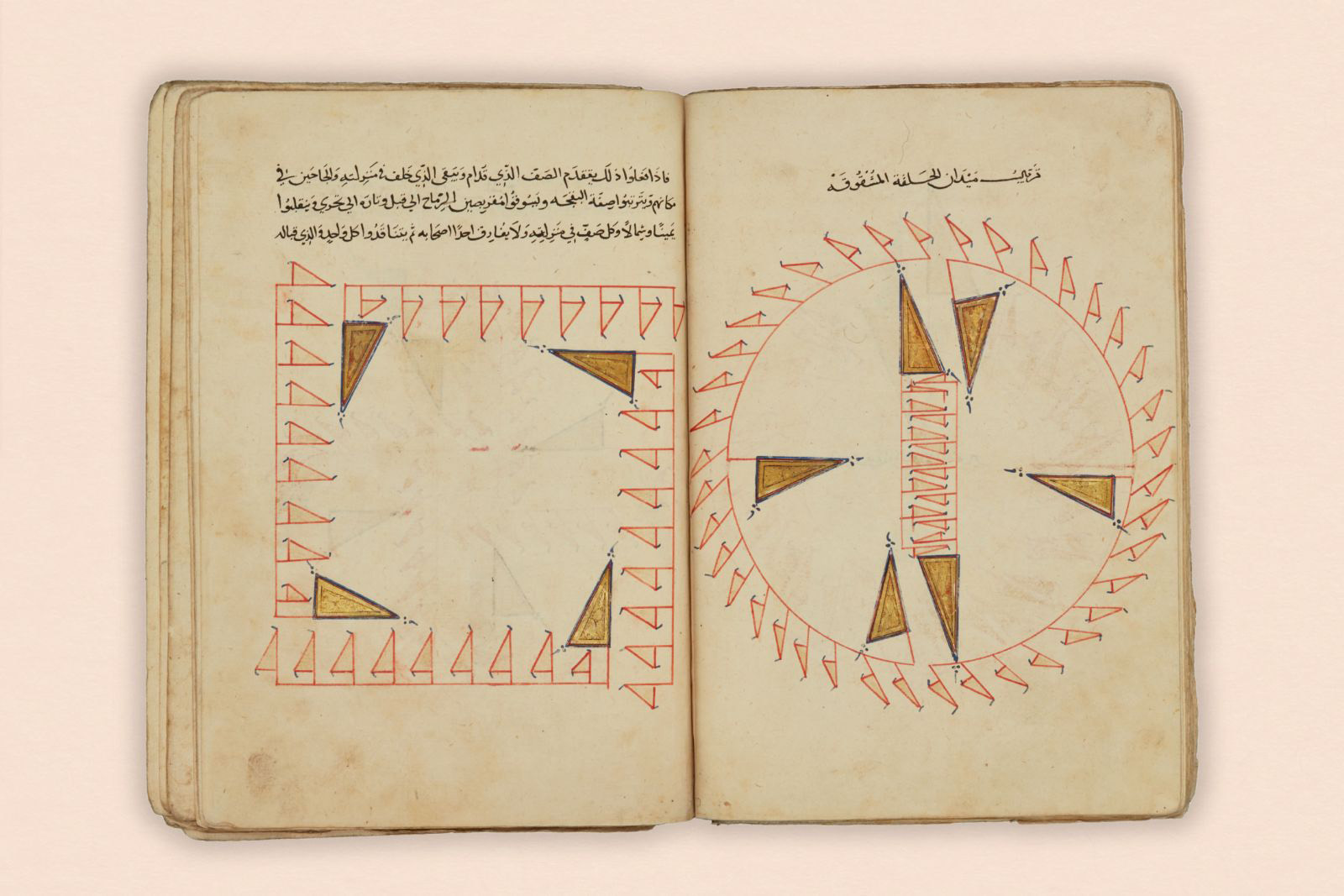

One day, Barker saw an Arabic manuscript on “the tactics of the lance”, detailing Ottoman cavalry battle plans. It was the perfect gift for his friend, the Egyptologist and Tory MP William Bankes. The manuscript made its way to the stately home of Kingston Lacy, where Bankes was born and lived.

For many years the sumptuously illuminated text, replete with diagrams showing the formations and movements of mounted soldiers in clean red lines and gold triangles, was stored with papers and notes from Bankes’ Egyptian travels. It now forms part of an archive of more than half a million items of historical significance kept across the 500 properties managed by the National Trust.

Bankes was not just interested in military history. His library also included a Quranic manuscript dating from the mid-16th century, which potentially originated in central Asia. Such items, it turns out, were surprisingly common in the grand homes of Victorian England. Accordingly, the trust is undertaking a painstaking survey of all the objects within its collection that have a connection to the Islamic world.

Related content

Samantha Brown, a doctoral researcher at University College London, has been tasked with researching the provenance of this treasure trove of artefacts and, where possible, finding out how they arrived in the UK. “It became this really fun detective work for at least two of the properties, to work out where these manuscripts had come from,” Brown says.

“What’s really nice about them is that they’re in the properties where they’ve been for potentially centuries,” she adds, “I’ve been really struck by how Qur’ans are everywhere.”

“There’s this really interesting collection of about 40 or 50 Islamic manuscripts that are spread across all of our properties,” adds Tim Pye, the trust’s national curator of libraries. He goes on to explain that the trust has brought in expert help to gain a true understanding of this strand of its collection and better engage with communities for whom the items hold special interest and value.

Talking to Brown and Pye, it emerges that the Qur’an held once widespread appeal for the English upper classes. A copy was given to Winston Churchill, Rudyard Kipling owned several and a 17th-century version that probably originated in west Africa sits in the library of Greenway House in Devon, home of Agatha Christie. The library at Dorneywood, a grace-and-favour home in Buckinghamshire owned by the trust and used by the chancellor of the exchequer, even features a fragment of a Qur’an believed to date from the 10th century.

“There’s also a doll’s house in one of the properties and they often would have a library room with miniature books. One of the miniature books is a Qur’an, which makes me feel like it was a staple part of a library in the period,” Brown says.

“I think you can see slightly different things happening through each of these collections,” Brown adds. Belton House in Lincolnshire was built by John Brownlow, 3rd Baronet, between 1685 and 1687. His nephew, John Brownlow, 1st Viscount Tyrconnel, inherited Belton in 1721 and built up the collection of books.

Tyrconnel was also part of the Spalding Gentleman’s Society, whose membership included Ayuba Suleiman Diallo, a Muslim of African origin who had been enslaved and taken to America, but bought his freedom and spent time in London as part of high society. Brown believes that Tyrconnel may have become interested in Islam through Diallo, leading him to acquire several manuscripts and printed books relating to Islam and the languages of the Islamic world.

In 1815 Bankes had undertaken a grand tour — an extended period of cultural travel enjoyed by affluent people from the 17th to 19th century. Many participants, including Bankes, journeyed through Europe and stopped off to study the art and ancient ruins of Italy, a country that, thanks to its trading relationship with the Ottoman Empire, was excellent for picking up books and artefacts from the Islamic world.

Related content

Calke Abbey in Derbyshire is home of the library of the 19th-century Egyptologist Sir John Gardner Wilkinson. It comprises the largest collection of Arabic manuscripts of all National Trust properties, with seven, while eight more now reside in Oxford University’s Bodleian Library.

Part of Gardner Wilkinson’s life’s work was an unsuccessful attempt to decipher ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs through an understanding of the Coptic and Arabic languages. Sharing the influential connections of many of the era’s collectors, he was also friends with Edward William Lane, who developed an important English-Arabic dictionary, published in sections from 1863.

“The collectors themselves might be directly involved in Empire and colonial power, or like Bankes, not employed by the British Empire or the East India Company, but have friends who are,” says Brown, “They were using the infrastructure, the routes that they had across the region, to send objects to him.”

Under the trust’s stewardship, these artefacts are no longer the preserve of a wealthy elite. The organisation is, however, waiting for conservation assessments to be made on a number of items before any exhibitions can be planned.

Pye hopes that, in the long term, his work will lead to this rich repository of manuscripts and historical objects being more accessible to the general public. He also believes that their stories can shine a light on the interconnected past of Britain and the Islamic world.

“We can really make these things kind of come alive and be relevant to people,” he says.

Four National Trust properties with Islamic links that you can visit

Kedleston, Derbyshire

Kedleston was the home of the Curzon family, one of whom was the Viceroy of India from 1899 to 1905. George Curzon also travelled extensively across Asia and amassed a substantial collection of artefacts including Turkish Iznik ceramics from the days of the Ottoman Empire.

Powis Castle, Powys

This Welsh National Trust property dates back to medieval times. It also has the largest private collection of south and east Asian artefacts in the UK, built up by two generations of the Clive family, including a book of verse by the Persian poet Ḥafeẓ.

575 Wandsworth Road, London

Visits to this 19th-century terraced house in south-west London are only available on a pre-booked basis. In the 1980s, the property became the home of Kenyan-born artist and civil servant Khadambi Asalache, who spent more than two decades transforming the space with intricate fretwork influenced by Islamic architecture.

The Argory, County Armagh

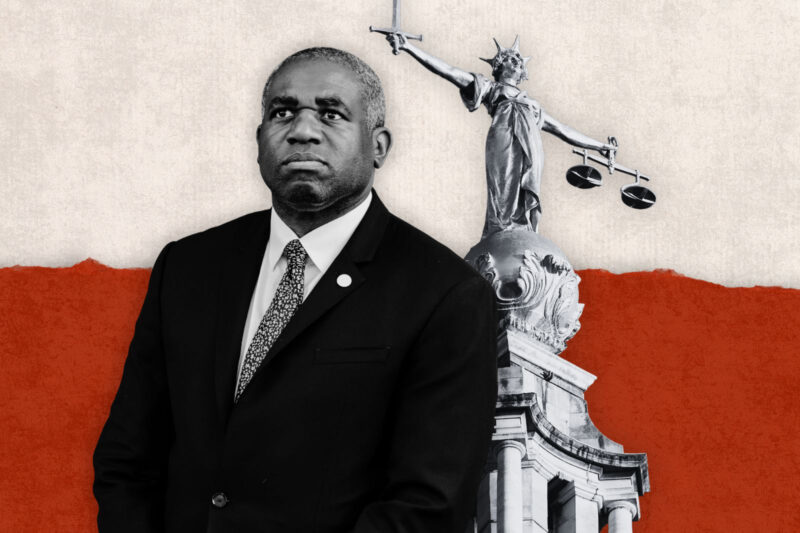

This imposing Northern Irish mansion was built in the 1820s and houses a significant collection of Islamic artefacts. Objects from Egypt and the Ottoman Empire, including swords, medals, manuscripts, carpets and even a model mosque were given to Sir Walter William Adrian McGeough Bond during his time serving as a high court judge in Egypt at the turn of the 20th century.

Newsletter

Newsletter