While We Wait: exhibition tells stories of displaced women in Jordan

In 2023 Rayna Carruthers travelled to Jordan to learn Arabic and volunteer with a refugee charity and began taking portraits of the women she met. Photograph courtesy of Rayna Carruthers/Nick Derenzi

Rayna Carruthers’ photographs showing at the Glasgow Women’s Library reflect personal stories of displacement from Sudan, Yemen and Somalia

Rayna Carruthers is a photographer based in Edinburgh using art to explore migrant experiences. In 2023 she travelled to Jordan — a country which hosts the world’s second-highest number of refugees per capita — to learn Arabic and volunteer with a charity helping refugees facilitate internet literacy and language classes.

Carruthers began taking portraits of the women she met who had been forcibly displaced from their home countries. The series of portraits, titled While We Wait, tells the stories of 11 women and girls from Somalia, Sudan and Yemen who reached Jordan after fleeing their homes. The exhibition, which is currently on display in the Glasgow Women’s Library, reflects on their experiences of living in uncertainty as they await resettlement to North America and Europe.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What inspired you to explore themes of displacement in your photography?

I’ve always been drawn to the topic of migration. My grandparents came to the UK from Barbados and Trinidad, so I have grown up on stories about their migration to this country and how they weren’t welcome. Whereas I grew up on the south side of Glasgow and experienced Scotland as a diverse place. My school was very proud of being very multicultural, with over 50 languages spoken by our students.

I began volunteering with refugees in Scotland and I saw Syrians, many who had started arriving from 2015, experiencing the same thing in this country as my grandparents did as immigrants. I wanted to understand what was happening. I wanted to look away from the stereotypes of migrants and how immigration was being explained to people by politicians.

Tell us about the series of portraits in While We Wait.

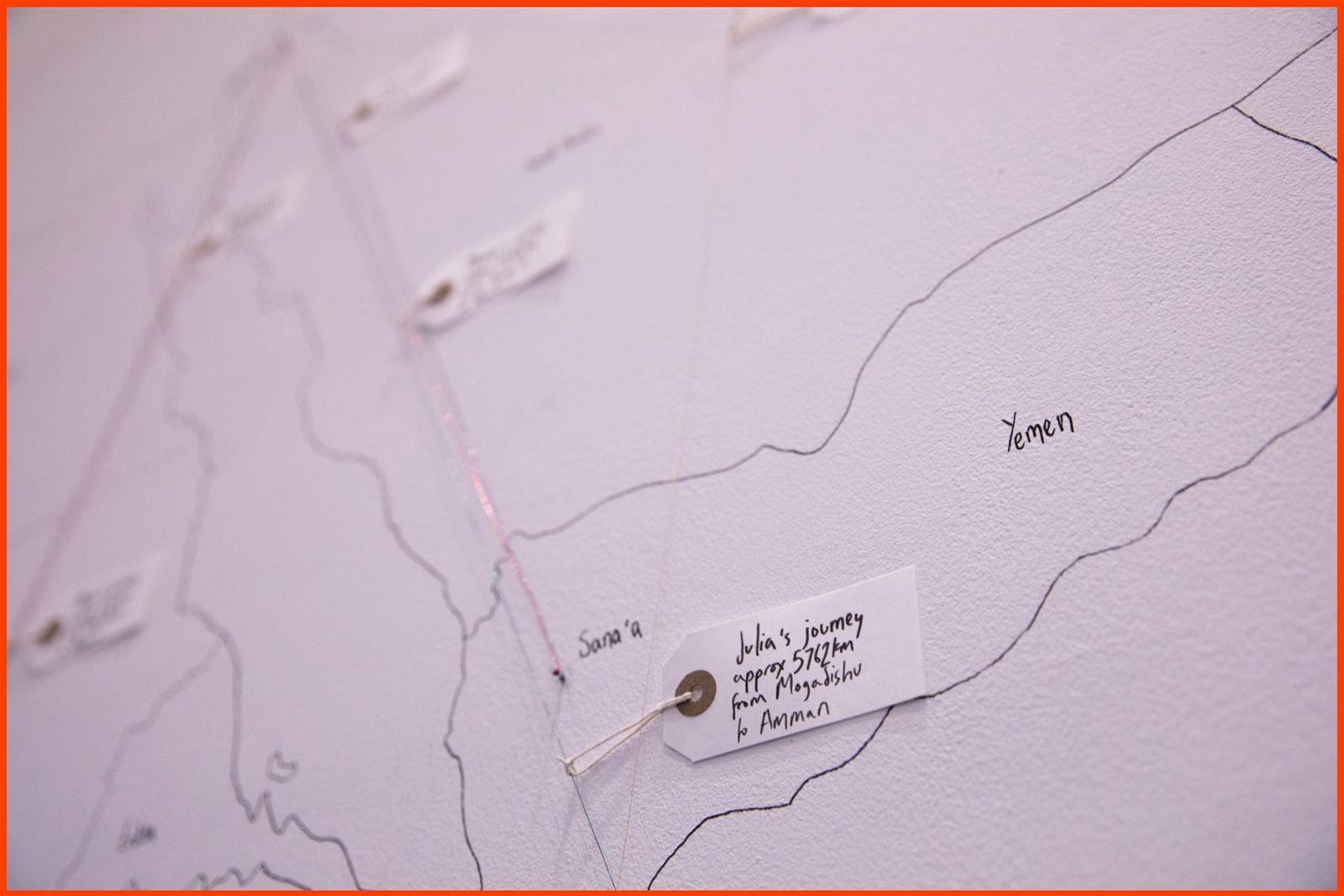

I met many women from Somalia, Yemen and Sudan who had all been displaced by conflict. Some had been victims of terrorism. One Somali woman, Julia (not her real name) had been homeless and lost her family to political violence, and eventually made her way to Jordan.

I started taking portraits of these women, firstly to just get to know them better. I was photographing and interviewing them, trying to understand more about their protracted situation of displacement. But I really wanted them to be part of this project and build the experience together. So after I took their photographs, I discussed the images with them, what they liked or what they wanted to change about the portraits. I love portraiture because it can be very collaborative.

How did you work together with them on their portraits?

Many of them were very aware of what they wanted the photographs to portray. For example, I photographed Fatouma from Somalia, who has been waiting for resettlement for more than 16 years. When I showed her the first photograph she said, “no, photograph me again”, and she then put on a very sad and sombre expression. I think she was aware of how people will look at her portrait, and she wanted to portray the idea of a refugee being trapped and having no options for where they could go to start a new life. It was important for me to show her in the way that she wanted to be shown.

You are photographing vulnerable people, how do you consider the ethics within your practice?

I didn’t want them to feel that the experience of being photographed was damaging or uncomfortable, so I tried to make it as collaborative as possible.

Fatouma, for example, had been interviewed by a couple of journalists during her first year in Jordan. Although she wanted people to hear her story, I think she felt a little bit disappointed by that experience, as she had hoped her story would get more attention and change her personal circumstances. So many of these women had promises of opportunities and resettlement like this that had been broken.

What do you hope people will learn from this exhibition?

When I first took Fatouma’s photo she said: “Please show as many people as you can. Show them my picture, tell them my story.” So it’s good that people are now getting to see these stories, and I hope viewers will feel more connected to the women in the photographs.

There’s such a disconnect between reality and the political discourse around the broken migration system — what asylum seekers have to do to survive and the limited options available to them, versus the idea that their presence in countries like the UK is a net negative. I really hope that projects like this can help illuminate why people end up putting themselves in danger and come to the UK on small boats, for example.

Ultimately, most of these women are still awaiting resettlement, so there’s a sad element too. But getting to see the way that they are able to continue living, hoping, dreaming for the future is inspiring. They’ve continually been making opportunities for themselves despite the uncertainty in their lives. I’m really in awe of them.

You went to Jordan to learn Arabic. What drew you to this language?

In the UK, especially during the protests for Gaza, the Arabic language has been misunderstood and used as a political tool. For example when former Conservative immigration minister Robert Jenrick called for the phrase Allahu Akbar to be banned in public or when protestors were accused of inciting terrorism for using the word jihad. Understanding Arabic made me more resistant to this type of politicisation of the language. I believe languages can break down walls between people and help us better empathise with other communities.

While We Wait is showing at the Glasgow Women’s Library until 29 March.

Newsletter

Newsletter