Islamophobia, Israel, Gaza and ‘culture wars’: Hyphen’s guide to Kemi Badenoch

The new Conservative leader wants to ‘renew’ the Tories. What does that mean for British Muslims?

Editor’s note: this article was updated on 6 November 2024 to include comments made by Kemi Badenoch about Donald Trump’s re-election.

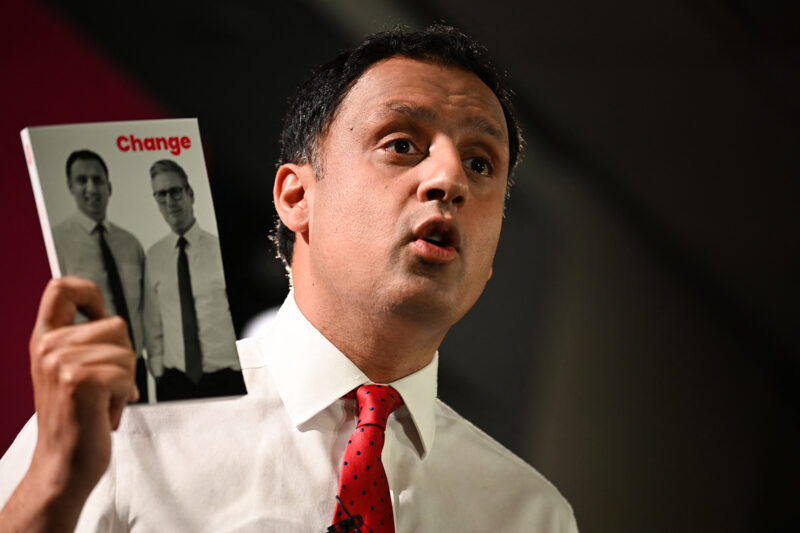

Kemi Badenoch won the Conservative leadership election on Saturday, defeating her opponent, Robert Jenrick, and becoming the first Black woman to lead a major British political party.

The former shadow housing secretary secured 56.6% of the 95,000 votes among eligible party members.

“The time has come to tell the truth, to stand up for our principles, to plan for our future, to reset our politics and our thinking,” Badenoch said in her acceptance speech. “It is time to get down to business. It is time to renew.”

Here is Hyphen’s guide to the new leader of Britain’s official opposition party — and what she thinks about discrimination, the term “Islamophobia”, Israel’s war on Gaza and more.

What are Kemi Badenoch’s political priorities?

Badenoch, like Jenrick, comes from the right wing of the Tory party. She campaigned for the leadership on a platform of “renewing” the party and focusing on Conservative values. But unlike her rival — who promised to cut benefits to fund tax cuts, leave the European Court of Human Rights and deport people without the right to live in the UK — she has avoided making specific policy commitments.

“Our starting point must not be policies, but principles,” she wrote on her website, though in her acceptance speech on Saturday she noted that she and Jenrick “don’t actually disagree on very much”.

Sunder Katwala, head of the think tank British Future, told Hyphen: “Badenoch has not made pledges to the membership about what the government would do in five years’ time. She’s said it’s too early for that. Instead she’s focused on values.” Those values, he explained, included “scepticism about the role of the state and more of a belief in the individual and the market”.

Previously, Badenoch has been outspoken on so-called “culture war” issues, vowing to “never shut up” about the “divisive agenda of identity politics” — such as Labour’s proposed Race Equality Act, which would extend full equal pay rights to ethnic minority workers and disabled people, and which Badenoch has criticised; or Labour’s suggestion of specific legal protections for workers experiencing menopause, a move Badenoch previously compared to extending the existing Equality Act to people who are short, single or ginger.

The Conservative party, of course, is not currently in government. But the opposition and its leader play an important role in determining the fronts on which Labour will have to defend itself both in parliament and in the media. Katwala expects that Starmer’s government, which has largely taken a more centrist position on “culture war” subjects, will work to steer the debate towards policy, the economy and the budget to avoid drawing unwanted attention from right-wing media and keep the focus on what it considers to be its strong points.

“Any government needs to engage with issues of identity and integration,” he said. “But they probably don’t want a left-versus-right fight with Badenoch about issues of identity or ‘wokeness’ as opposed to government performance, health services and so on.”

However, he noted that topics of gender and race identity have been less present in Badenoch’s rhetoric during the leadership race than in her previous statements, and suggested they may therefore disappear from centre stage as she grows into her role as “an alternative prime minister”.

Shehab Khan, ITV News’s political correspondent and Hyphen contributor, agreed. “Often the way people campaign and the way they govern are slightly different,” he said.

What does Kemi Badenoch think about Israel and Palestine?

In a sympathetic interview with the Jewish Chronicle in June, Badenoch said she rejected the “oppressor vs oppressed narrative” about Israel’s bombardment of Gaza and said she had co-sponsored a Tory bill to ban public bodies from involvement in boycott, divestment and sanctions against Israel. The bill was abandoned when the election was called.

She also suggested that attendees at the UK’s regular and sizeable peaceful demos in solidarity with Palestine were either “deeply misguided” or motivated by hate.

Badenoch has been publicly critical of the government’s position on Israel, condemning its recent decision to suspend 30 of the UK’s roughly 350 arms export licences for firms to send military equipment to Israel. The decision would “weaken our position in the global fight against Iran and her terrorist proxies”, she said.

During her parliamentary career, Badenoch has built a reputation as a staunch ally to Israel and in September told Sky News that the country was “showing moral clarity in dealing with its enemies and enemies of the west”.

Asked in the same interview what she would say to Britain’s allies if she were leading the Tory party, she replied: “I would be congratulating Prime Minister Netanyahu.” She also referred to Israel’s response to the 7 October 2023 attacks as “extraordinary”. The UN’s special rapporteur on human rights in the occupied Palestinian territories has accused Israel of committing acts of genocide in its response to the attacks by Hamas, which Israel denies. The International Court of Justice, in response to a case brought by South Africa, did not make a ruling on whether Israel was committing genocide — but did order it to take steps to prevent further harm to the Palestinian people, something Amnesty International says Israel has not complied with.

What is Badenoch’s stance on Islamophobia?

During her parliamentary career, Kemi Badenoch has criticised the use of the term “Islamophobia” which she believes impedes on the right of the British people to criticise religion. She has advised Muslims to instead use the term “anti-Muslim hatred” to describe targeted abuse they face due to their religion.

Instances of discrimination faced by British Muslims, however, largely failed to capture her attention as equalities minister, and she has seldom identified specific examples of “anti-Muslim hatred” taking place in the UK. While Badenoch held the equalities brief, the government refused to condemn former Tory MP Lee Anderson, who claimed that “Islamists” had “got control” over London’s mayor, Sadiq Khan, who is Muslim.

“I am afraid the deafening silence from Rishi Sunak and from the cabinet is them condoning this racism,” Sadiq Khan told Sky News.

Although in a speech during Islamophobia Awareness Month Badenoch said that “hatred of Muslims is a vile social ill”, she has been accused of Islamophobia herself — most recently by Jeremy Corbyn and the four Muslim MPs who had joined parliament as independents. Badenoch said the MPs were “elected on the back of sectarian Islamist politics” and “alien ideas that have no place here”. One of the MPs, Birmingham Perry Barr MP Ayoub Khan, responded in a piece for Hyphen by saying that Badenoch’s comments were “deeply offensive” and could encourage violence and threats.

In April, while holding the post of faiths minister, Badenoch praised a court’s decision to uphold the ban on prayer rituals introduced by Michaela community school in Brent, which Muslims students said prevented them from performing salah during lunch breaks.

“This ruling is a victory against activists trying to subvert our public institutions,” Badenoch said on X. “No pupil has the right to impose their views on an entire school community in this way.”

Responding to Badenoch, Abdul-Azim Ahmed, secretary general of the Muslim Council of Wales, told PA media: “I think unfortunately the minister’s comments are sensationalising this case and playing into a culture war and a rhetoric which doesn’t reflect the reality of what’s happening on the ground.”

However, ahead of the leadership vote, Badenoch was urged to tone down her “abrasive” rhetoric by fellow Conservatives. In a BBC interview a couple of weeks earlier, she had turned her fire on recent immigrants from “less valid cultures” who hate Israel. Asked who she meant, she said: “You want me to say Muslims, but it isn’t all Muslims.”

Badenoch’s first session of the weekly prime minister’s questions (PMQs) as opposition leader on 6 November coincided with the re-election in America of Donald Trump. She took the opportunity to establish herself as an ally of the incoming US president, who ran partly on a platform of reinstating his “Muslim ban”, the 2017 executive order that imposed a travel ban on people from seven majority-Muslim countries.

At the despatch box she demanded an apology from Keir Starmer on behalf of the foreign secretary, David Lammy, who called Trump a “neo-Nazi sympathising sociopath” in 2018.

She also called on Starmer to invite Trump to address parliament on his next visit to the UK.

Does it matter who leads the opposition?

Leader of the opposition is an important role and a paid position that comes with an extra salary. It is up to the opposition leader to scrutinise and hold the government to account and they play a crucial part in PMQs, setting the agenda for the event.

“The leader of the opposition is given a platform above every sitting MP that doesn’t serve in the cabinet,” said ITV’s Khan. “They get advance notice of major announcements. They are often briefed on the biggest security issues as well. Constitutionally, it is such a crucial role.”

The opposition serves more than just a rhetorical function. It can not only question and point out flaws in the government’s arguments; it can also work to delay or even prevent the implementation of policies it does not like, although this is unlikely to happen given Labour’s current large majority. All the same, the opportunities for these kinds of “political ambushes” abound, as Gillian Shephard, a former Conservative shadow minister between 1997 and 1999, wrote in 2000.

One of the most common tactics is putting forward a motion or an amendment to a bill in the Commons to force a debate on a particular subject “where a well-drilled opposition can tease out the flaws in the government’s arguments”, Shephard wrote. She added: “Planned and concerted attacks, against, for example, a minister under threat from his own side, or a policy where government MPs are likely to rebel, are also useful weapons for the opposition … Some of the most effective tactics are those which cause government backbenchers to complain bitterly to their whips.”

Then, of course, the leader of the opposition features prominently in the media — broadcast regulators require opposition parties to be given a certain amount of airtime — and will set the tone for her shadow ministers’ own appearances on radio and TV and in newspapers. She may for instance, decide to attack Labour on the issue of taxation, or public services, or her perennial favourite of culture war issues — which could turn them into public talking points.

Put simply, the opposition works to weaken the government and set roadblocks in its path when possible, while painting a picture of an alternative government that the party can present to the public at the next election.

How big a threat is the opposition to the current government?

Following the last election the Labour party has the biggest majority of any government in modern British history. That means the scope for the Conservatives and other opposition parties to block government bills and policies is limited, as a large number of Labour MPs would have to rebel to ensure a government defeat in parliament. Rather, Badenoch’s main aim as opposition leader will be to build up a fresh party profile and present herself as a credible alternative to Keir Starmer at the next election.

“Badenoch is fighting a war on three fronts,” said Shehab Khan. “In a lot of constituencies, Reform came second. Liberal Democrats also took away many Tory votes. She will need to win votes back from Labour, Reform and Lib Dems — this will be a huge challenge.”

But he still expects Badenoch to bring a new, more confrontational, approach to PMQs. “Badenoch will be much more on the front foot and she is going to come at Keir Starmer in a way that Rishi Sunak did not. It is going to change the temperature quite a lot,” he predicted.

Badenoch has called her campaign Renewal 2030. “2030 is the first full year we can be back in government, at the beginning of a new decade,” she wrote on her campaign website. “We have to make sure we are ready for those challenges, with a clear vision for the future, not litigating the battles of the past.”

Newsletter

Newsletter