Bangladeshi students and activists have legitimised their commitment to democracy

Recent protests show that for the first time in years Bangladeshi citizens at home and abroad feel a sense of ownership about the future of their country

It is not every day that an uprising delivers on its promise of overthrowing an unpopular government. On 1 July students across Bangladesh took to the streets, demanding an end to government job quotas that reserved almost one third of posts for children and grandchildren who fought for independence from Pakistan in 1971.

The following weeks saw widespread anti-government protests, mass arrests and a violent state crackdown leading to the killing of hundreds of demonstrators across the country. The government’s actions were lifted out of the authoritarian playbook; they issued a nationwide curfew with a shoot-on-site directive, and the army was deployed for the first time in almost 20 years. The Bangladeshi diaspora watched in horror as internet connectivity was shut down in the name of “public safety”, stopping students from sharing information and making plans on social media, and throttling the flow of information in and out of the country as the first reports of state violence emerged in mid-July.

When, on 5 August, prime minister Sheikh Hasina resigned and fled to India by helicopter, the mood oscillated between shock and jubilation.

The violence on the streets had been an outpouring of discontent after 15 years of Hasina’s iron-fisted oppression which included forced disappearances and corruption. While the country of 170 million experienced an economic miracle during the first decade of Hasina’s rule, albeit amid rising income inequality, the last five years had seen a surge in inflation and joblessness largely attributed to a mishandling of the economy and poor policy decisions.

But over the past few weeks disinformation has been widespread across the political establishment and social media, where the student protest movement and anti-government uprising were characterised as both an Islamist plot designed to destabilise Bangladesh and a national security threat for neighbouring India.

Still, amid the conspiracy theories shared across platforms such as X, it was clear that the uprising had created a valuable digital space for ordinary people to discuss the future of democracy in Bangladesh. Watching this political drama play out in real time from Dhaka, where I was for the summer, while friends and colleagues in the US and the UK were glued to their screens asking for updates and strategising how to be useful, I saw for the first time in many years that citizens felt a sense of ownership about the future of their country. They were excited to have a say in it.

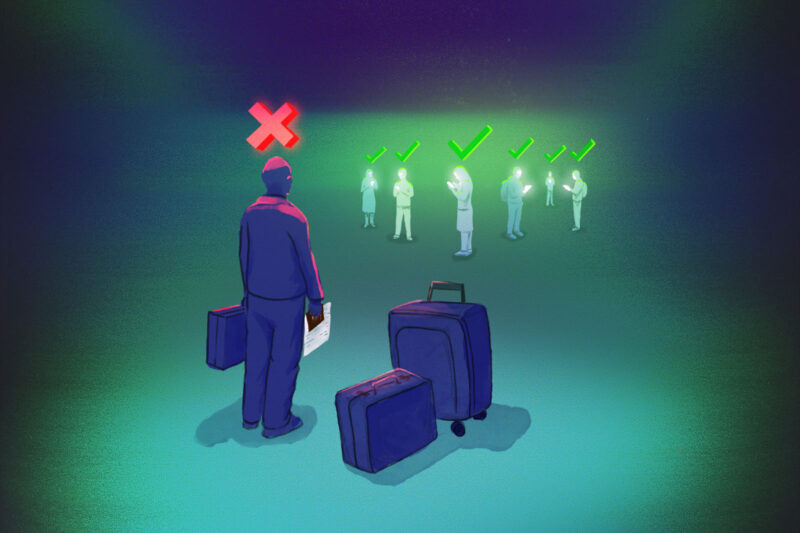

In the face of disinformation, Bangladeshis and the wider diaspora were spurred into action, fighting online battles that mirrored the unrest on the streets of Dhaka. From responding to increasingly unhinged online videos posted by the former prime minister’s son, to correcting Islamophobic hot takes in the US and Indian media, Bangladeshis fought disinformation with facts.

For example, in the days after Hasina’s fall, her son and official adviser, Sajeeb Wazed Joy, gave interviews warning of the suspected involvement of Pakistan’s powerful Inter-Services Intelligence in provoking the student unrest, and suggested the nation would become a crucible for religious extremism without the Awami League at the country’s helm. American economist Jeffrey Sachs later accused the US of “regime-change operations” in Bangladesh.

Activists and scholars challenged these attempts to take agency away from students and to ascribe the uprising to foreign forces. Indeed, fighting disinformation became an organising tool to build solidarity between students and citizens in and outside Bangladesh. Instagram accounts such as @thebangladeshivoice in the UK and other independent media became go-to sources as the government cracked down on local media.

The diaspora also mobilised offline, using more traditional routes to appeal to the international community. One group of activists successfully spearheaded a plan to halt remittances returning to Bangladesh, aimed at ratcheting up economic pressure on the regime. Bangladeshi academics in the US and Canada put together a shared document with links to media coverage of the movement, while another provided analysis and information to international media. Across the US, the UK, Australia, the United Arab Emirates and elsewhere, protests were held in front of Bangladesh embassies.

This powerful instance of global protest and solidarity — both online and offline — is cause for immense hope. It also marks a rare display of trust between students and ordinary Bangladeshis at home and abroad. Yet there are also lessons to be learned in the fight between truth and disinformation. Social location matters: what appears true in suburban American homes, for instance, may not be true for those fighting deadly force on the ground in Dhaka. While the threat of Islamist terrorism may have been manufactured, there are ways in which such conspiracies can be made very real. What appears to be an efficient economic weapon to weaken the government from our middle-class positions could produce a deep crisis for the working poor in Bangladesh.

The removal of Hasina is ultimately a fierce reminder that an oppressive neoliberal state machinery can be overcome, even when people are suppressed by formidable forces such as an increasingly authoritarian government and armed forces.

The 2024 student movement follows in the footsteps of student movements that brought independence to Bangladesh in 1971 and overthrew a dictator in 1990, underscoring the enduring strength and resilience of the student body. By coming together, students and activists have legitimised their commitment to a democratic future.

As the aftereffects of the uprising settle, with an interim government in place led by the Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, the country is, I hope, entering an era of reconciliation while tackling a fundamental overhaul of the state, and a renewed trust with its citizens.

Newsletter

Newsletter