Looking to landscapes for peace after decades of trauma

A debut memoir by a British-Pakistani author looks to the flat lands of the UK and Pakistan to find healing

–

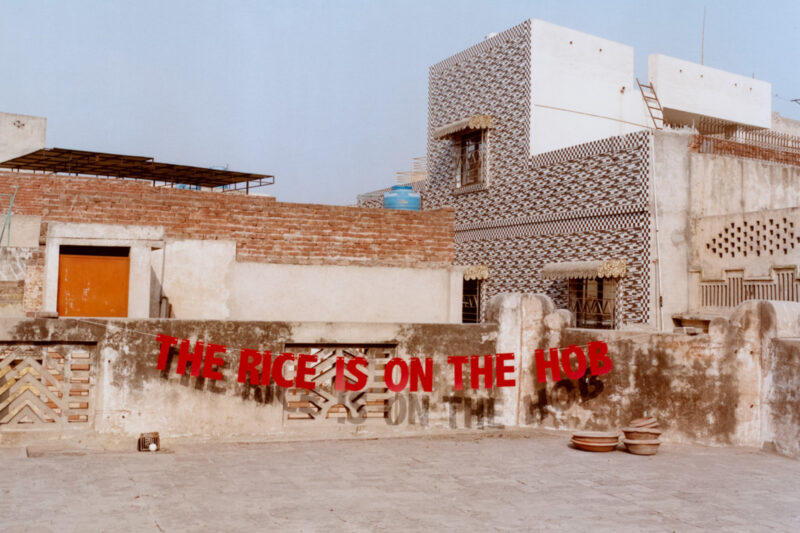

Flat lands, like the tidal areas of Morecambe Bay or the Scottish Orkney archipelago, can feel both boundless and constraining. British author Noreen Masud originally wanted to write about these environments because of a memory from her youth in Pakistan. This childhood in Lahore was deeply unhappy, as her controlling doctor father kept his British wife and their four daughters largely confined to their home. The girls were only allowed out to attend school. In the car, Noreen would stare out of a window finding solace in gazing at the flat farming fields she saw ribboning away from Lahore’s urban sprawl.

Masud’s debut, the travel memoir A Flat Place, comes out of this and other experiences of even terrains. The author, a lecturer in 20th-century literature at the University of Bristol, offers a multifaceted exploration of trauma, landscape and the impact of colonialism. At 15, her parents divorced, and her father disowned all but the youngest of the sisters. Teenage Noreen found herself living with her mother in Fife on the east coast of Scotland and then studying English Literature at Cambridge University. Her unusual and emotionally-charged nature writing takes in five British locations, including Ely and the Fens in Cambridgeshire, the shingle spit of Suffolk’s Orford Ness, and the common land of Newcastle’s Town Moor.

Masud has long grappled with her near-total separation from society in Pakistan, leading to a diagnosis of complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD). The condition’s challenges include derealisation (where everything seems unreal) and difficulties with intimacy. The PTSD we associate with warzones revolves around flashbacks to life-altering traumatic experiences. By contrast, CPTSD has no such landmarks, but results in endless exhaustion from having never felt safe. While there was no climax to her father’s cruelty, Masud associates the flatness of the lands she is drawn to with the flat affect of her CPTSD.

In describing her CPTSD, Masud highlights the postcolonial trauma Pakistan still suffers. Many of the experiences Noreen endured were consequences not of Islam, but of the injustices wrought upon the subcontinent by the British Empire. For Masud, with her Kashmiri and Pakistani heritage, most damaging of all were Cyril Radcliffe’s Partition borderlines, which led to the creation of an independent India and Pakistan. Born out of British ignorance, reckless speed, and self-interest, these borders resulted in the blood-drenched birth of two nations in 1947. According to the author, only against this political backdrop can the personal tragedies of her father’s violence be understood.

Her travel memoir also addresses some important contemporary issues. The book’s British sections highlight the injustice of colonialism. By shedding light on modern slavery through the deaths of at least 21 illegally trafficked cockle-pickers in Morecambe Bay in 2004, the author emphases the realities of labour exploitation in otherwise idyllic landscapes. At Orford Ness, she confronts the hidden history of the Chinese Labour Corps which fought for the Allies during the first world war. At Newcastle’s Town Moor, she researches the shameful history of the human zoo, inhabited by a hundred Senegalese people and held there in 1929. In gift shops and antique shops along Masud’s journey, the author encounters the triggering presence of ornamental golliwogs.

Sections of Masud’s memoir shed light on her Pakistani heritage. As a politically astute British Asian, the author seeks to subvert the dominant anti-Pakistan and Islamophobic stereotypes commonly deployed in many so-called Muslim misery memoirs. These are autobiographies, usually written by ex-Muslim women writers, which often present an exaggerated picture of suffering and oppression under Islam. Masud takes pains to show that if her father was “culturally conservative”, he was far from conventionally religious or misogynistic.

Western assumptions about the global south are also interrogated. A Flat Place touches on the widely held perception in the West that people of colour often have an infinite capacity to absorb suffering with no negative impact. According to Masud, this is because the West does not see people of colour as fully human. When she would tell British people about her abusive childhood, they would act nonplussed, as though imprisonment were a normal thing for girls in Pakistan. A Flat Place exposes the one-dimensional nature of such assumptions by emphasising that such an upbringing was highly unusual for most Pakistanis.

One area where A Flat Place explores a vitally important contemporary point is in challenging the well-established narrative of exclusion and reclaiming a sense of belonging for brown people within natural environments. Masud shows that there have long been many people of colour in the British countryside; however, they are rarely there for leisure purposes and more often working dangerous, poorly-paid agricultural and fishing jobs. While expressing her love for flat lands, she simultaneously notes that these outdoor spaces “also contain the stretched pain of people of colour forced into difficult, dangerous work by border regimes, or omitted from histories where their presence is an inconvenience”.

The book was written during the global pandemic, and Masud presents an unconventional perspective on the first lockdown of 2020. Given her CPTSD, the writer largely enjoyed the unprecedented circumstances of the pandemic. For the mentally unwell, lockdown could serve as an unexpected release from the pressures and expectations of the outside world. Whereas others were preoccupied with “flattening the curve” or how flat they felt in their isolation, for her social distance was liberating.

In meditating on these and other intricate themes, Masud’s A Flat Place presents a startling rewrite of South Asian and British landscapes. By unsettling prevailing notions, the book establishes this young author as a profound new voice in contemporary literature.

Newsletter

Newsletter