Ayesha Manazir Siddiqi Q&A: ‘I’m interested in the unexpected feelings that rise up within us’

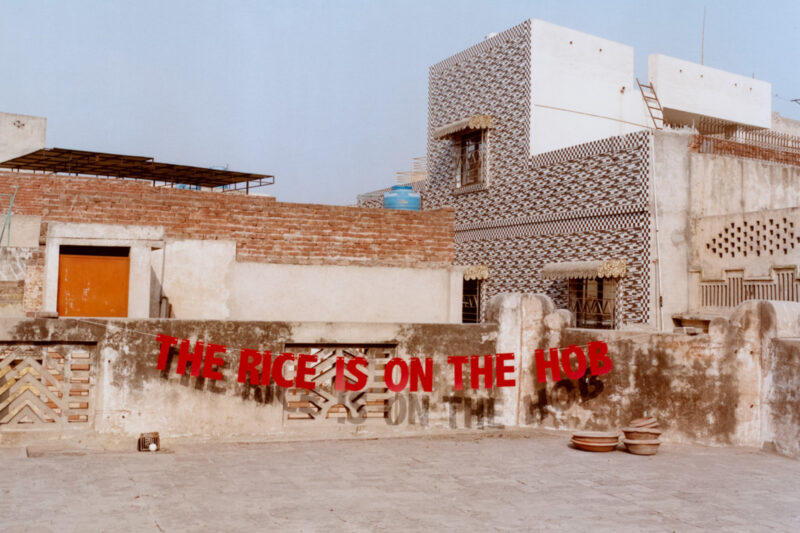

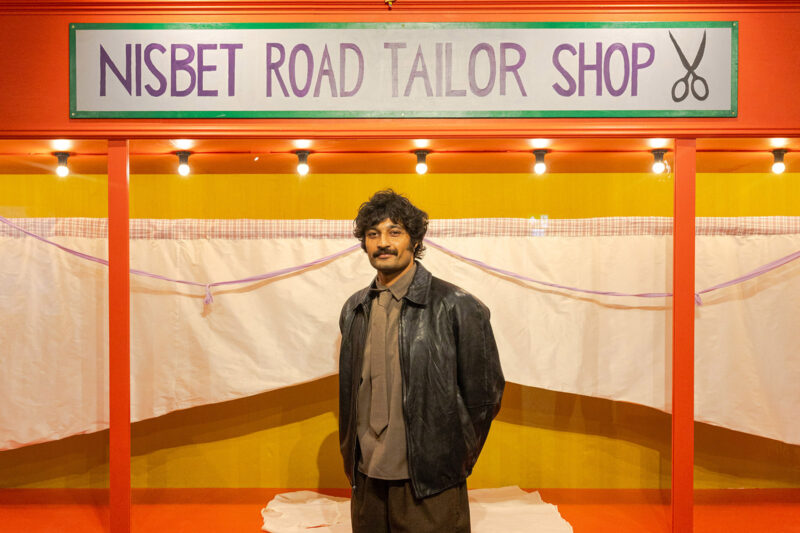

Ayesha Manazir Siddiqi’s debut novel The Centre focuses on a Pakistani woman living in London who subtitles Bollywood films. Photograph courtesy of Ayesha Manazir Siddiqi

The writer and author speaks about language, colonialism and the rollercoaster ride of writing a first novel

Ayesha Manazir Siddiqi is an editor, writer and translator based in South London. She has worked as a contributing editor on The Trojan Horse Affair podcast by the New York Times and Serial Productions, and her short essays and reviews have appeared in newspapers and magazines around the world. Now, her debut novel, The Centre, is about to be published by Picador UK.

The story focuses on a Pakistani woman in London who dreams of becoming one of the world’s great literary translators, yet spends her days joylessly subtitling Bollywood films. Her life is quickly upended when her boyfriend, Adam, enrols in a sinister language school that teaches him to become fluent in Urdu in less than a fortnight.

The Centre interrogates roles of race, class, religion and identity in British society. Here, the author talks about how her work delves deep into the relationship between language and colonialism and the challenge of writing her first book.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Anisa, the main character in The Centre, is an upper-class Pakistani woman living in London and struggling with the class divide in both places. How do you relate to her as a character?

Although there are many differences between me and Anisa, I did move to London from Karachi at 18 for university and I do come from a privileged family. There have also been situations in my friendships where I have found myself conveniently glossing over my own class privilege. Through her, I am trying to understand the things that one can overlook and take for granted.

Anisa is quick to see situations where she is marginalised, in terms of her gender, her sexuality, her Pakistaniness, her religion, but is slower to notice the class dynamics between herself and her boyfriend. This is common — we often find it easier to speak about the ways in which we are oppressed than the ways in which we oppress.

At the very start of the story, Anisa explains that translating a language is complex and that doing so well is all about retaining the feeling of the original words. You thread the Urdu language throughout the book. Did you encounter any difficulties in doing that?

There has been much talk in the publishing industry over the years about so-called “foreign” languages, about not italicising words or providing glossaries. I am grateful that these conversations have been taking place and for writers like Khairani Barokka and others who have been initiating the discussion. Those conversations have meant that I didn’t have to fight to keep Urdu words in my book. I didn’t even have to explain myself. I could write the way I think and the way I talk. That creates an intimacy that I think adds to the reader’s experience, whether they understand Urdu or not.

Language is a recurring theme in the book. For some readers, it will raise important questions about identity and colonialism. Was that your intention?

Anisa feels frustrated that her Urdu translations are going nowhere and one of the reasons she jumps on the opportunity to attend The Centre — despite the ominous mystery surrounding it — is that she can become instantly fluent in German, a language that she feels is more prized than Urdu or Hindi. She has internalised the idea that the language is superior to her own.

More often than not, romance is the dominant arc in fiction, either written or on screen, but you also concentrate heavily on female friendships?

Female friendships and sisterhoods have been instrumental in my own life, ever since I was a little girl. It’s through them that I have found the support to grow, to learn and to love. I find the prioritisation given to the heterosexual romantic relationship in storytelling annoying. It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy — the idea that is the only legitimate love.

Talking of that, Anisa develops some feelings for Shiba, the manager of The Centre, that takes her by surprise …

I am interested in the ways in which unexpected feelings can rise up within and make us question some of the beliefs we hold about ourselves. That’s one of the beauties of life and something that also sometimes requires courage to face. And I like that Anisa is curious about her desires, and that she feels that desire itself is an amorphous ever-changing thing, and that we have been trapped into binaries, but everything is far more fluid.

Prayer is an integral part of Anisa’s life. Do you feel that is the case for most Muslims?

I don’t think any two Muslims are alike, so I can’t say, but I do know that prayer is important to me. Just the act of writing a book — clearing all that time and space for a project that may very well go nowhere — is an act of deep faith. Prayer lets me know what is important to me. It affirms my deepest priorities and lets me investigate my own intentions.

You also address Islamophobia and the privilege that comes with not being visibly Muslim at times …

Yes, I address this especially in the scenes set in India, where Anisa can pass as Indian and non-Muslim, and the ways in which that protects her. It is easy to forget about solidarity in moments of privilege. The hardships of others become invisible when you are not subjected to them.

If you could go back in time, what advice would you give yourself before writing the book?

It’s been a bit of a rollercoaster, so maybe I’d just tell myself that. The publishing process is sometimes hard and can be overwhelming, but be kind, be gracious and make sure you’re not shutting any doors behind you. Remember the people who helped you get where you are.

Newsletter

Newsletter