The film festival opening the world to Kosovo

With Kosovo’s film-makers hoping the EU will finally ease its punishing visa regime, for a week every August, Dokufest brings the industry to them

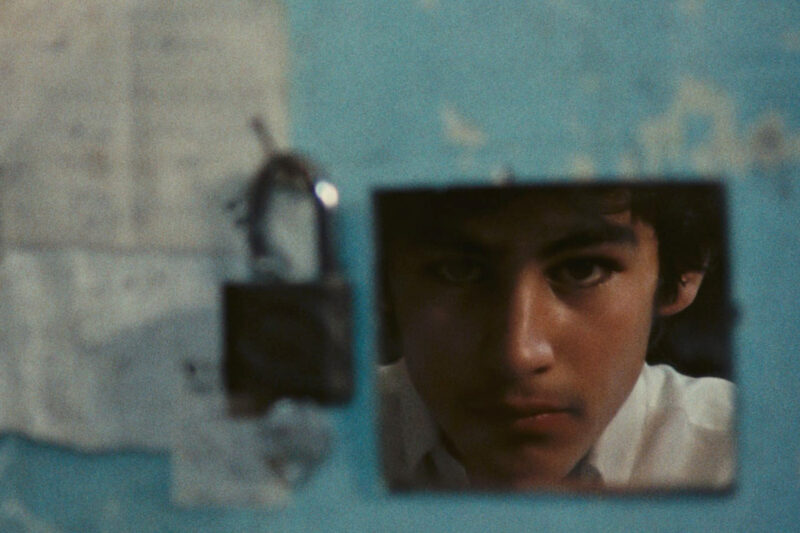

Director Leart Rama shot his short film Four Pills At Night (2021) at Bahnhof, a disused club inside Pristina’s train station. It was there that Kosovans experienced the first stirrings of underground club culture before independence in 2008. Covid threatened to derail production — but Rama, who is also a DJ and music producer, pressed ahead, resurrecting the venue in Kosovo’s capital for one more party and staging the action inside.

His film follows a young man grappling with a relationship crisis and violent discrimination on a night out. For the shoot, Rama invited 50 guests to the club. Scores more showed up, and he let the night unfold organically.

“Everyone said it would be impossible and the police would shut it down, but I was very determined to make it happen,” said Rama. “I create things based on what I feel and see in my daily life, and get inspired by real characters.”

A premiere at high-profile Swiss arthouse festival Locarno followed, and the 25-year-old got the green light to develop the film into a feature.

Four Pills joins a wave of recent Kosovan films gaining success on the global festival circuit. Some, such as Blerta Basholli’s Sundance-winning Hive (2021), aim to process the trauma of the Kosovo War of the 1990s. Others, including Rama’s, reflect a young, outward-looking generation — around half of Kosovo’s population is under 25 — eager to place the dynamism of their cultural scenes and personal stories in dialogue with a wider Europe.

The drive to create despite practical constraints is an attribute Rama credits Dokufest with stimulating. The film festival, Kosovo’s largest, has served as an inspiration and training ground for creative talent within the country’s borders, while citizens have been isolated from other European countries by a punishing visa regime.

“Most of the time in Kosovo it’s really, really hard to make films, especially when you have out-of-the-box ideas that are not related to war,” said Rama. “But, to this day, even the craziest ideas that I have, Dokufest are just like ‘go, you can do it’.”

Rama was 14 and had never touched a camera when he answered their open call for a KinoKabaret film workshop for no-budget micro-cinema. He caught the directing bug, and went on to Dokufest’s Future is Here filmmaking programme for high school students, and then to study Film Directing at the University of Arts in the Albanian capital, Tirana.

“It was pretty weird at first for my family and friends, because in Rahovec, the small town where I grew up, art in general is not very appreciated,” he said.

Long-standing promises by the EU for visa liberalisation, which have fuelled cycles of hope and disappointment for freer movement since Kosovo was given a visa roadmap in 2012, are set to be fulfilled in early 2024. In April, the European Parliament agreed visa-free travel for Kosovo citizens in the EU for 90 days. A sense of resentment that some parts of the continent are considered more “European” than others and afforded greater rights has affected a generation of Kosovans hungry to travel beyond their own borders.

“Even when I have a visa, they always stop me [at] passport control for 20 minutes asking everything they can. It’s dehumanising,” said Rama. “I don’t feel comfortable with how people from western countries see us, always below them, even if you do the most amazing things. For others it’s even harder. I know people who’ve been trying to get a visa for years and spent a lot of money, and it never happened for them.”

Four Pills star Redon Kika, 24, has channelled this frustration into creation. The short I Have Never Been On An Airplane (2020), which he directed, documents the feelings and dreams of three friends who had never flown outside Kosovo. It is now also being expanded into a feature-length film, shooting in Portugal, following the protagonists on their first European travels.

Dokufest, held every August along with associated music festival Dokunights, was founded in Prizren, Kosovo’s second-largest city, in 2002. Originally three nights of outdoor screenings organised by a group of friends in a city with no functioning cinemas, from humble beginnings it has grown into Kosovo’s biggest cultural event, and the most important documentary and short film festival in south-east Europe.

The event, held over nine days with a curated programme of more than 250 films and scores of invited international guests, also plays a crucial cultural role in introducing Kosovan film-makers and cinephiles to artists and images from around the world.

“If you were a 16-year-old here 10 years ago, the only good thing that happened to them was this festival,” said co-founder and artistic director Veton Nurkollari. “It became a kind of hidden mission of ours to bring the world to them, because they cannot go to the world.”

Nurkollari said he could never have envisioned today’s scale when he and his friends started Dokufest. “None of us had even been to a film festival before; we had zero references. It was right after the war, at a time when some sort of incredible energy was coming from somewhere. You don’t know where, but you think and feel that everything and anything is possible,” he said.

Dokufest works not only as a gateway for ideas and perspectives from outside Kosovo’s borders, but to revitalise grassroots culture and creative self-belief. While events like Sarajevo Film Festival in nearby Bosnia and Herzegovina have a strong red-carpet focus on celebrities, Dokufest has eagerly retained its roots in community action, an attitude that filters through from its staff to volunteers.

“It’s not only a place where we work, but part of our collective memory as citizens from Prizren,” said Alba Çakalli, Dokufest’s 33-year-old festival producer. “What Dokufest planted was this activism, to protect something that you consider as valuable for the city. We grew up with this.”

She was appointed to the key role three years ago, having first joined the festival as a teenage volunteer. “When I was 15, being part of Dokufest was a very big, prestigious thing for us,” she recalled. “We didn’t even know what it was at first, but all the coolest people in Prizren worked there.”

Her first involvement as a volunteer was collecting signatures to save cinema Lumbhardi, built in 1952 in what was then socialist Yugoslavia, from privatisation and demolition. She was led by co-ordinator Hajrulla Çeku, who is now Kosovo’s Minister of Culture, Youth and Sport. Çakalli had only seen one movie in Lumbhardi — Batman, at age six, with her uncle — before the war came and the cinema’s doors were shut.

Lumbhardi was saved, becoming the hub of Dokufest, and Prizren now has 16 cinemas and a revived movie-going culture.

“The spirit of Dokufest is that when you do something with passion, and really believe in it, you don’t need the red carpet,” said Çakalli. “Dokufest does not have this glamorous thing that is visible to the eye. It’s a movement that teaches people culture is a lifestyle. You don’t have to change and do something beyond yourself to deliver a message or connect with the audience.”

The lifting of EU visa restrictions should ease Kosovo’s cultural isolation and encourage foreign travel, but will it also transform Dokufest’s mission? “The festival will simply adapt, as we always do,” said Çakalli. “It’s been a really big part of Prizren for 22 years. Apart from just doing what is written in our contracts, we have a responsibility to deliver it to other generations.”

Dokufest will take place in Prizren, Kosovo, this year between 4 – 12 August

Newsletter

Newsletter