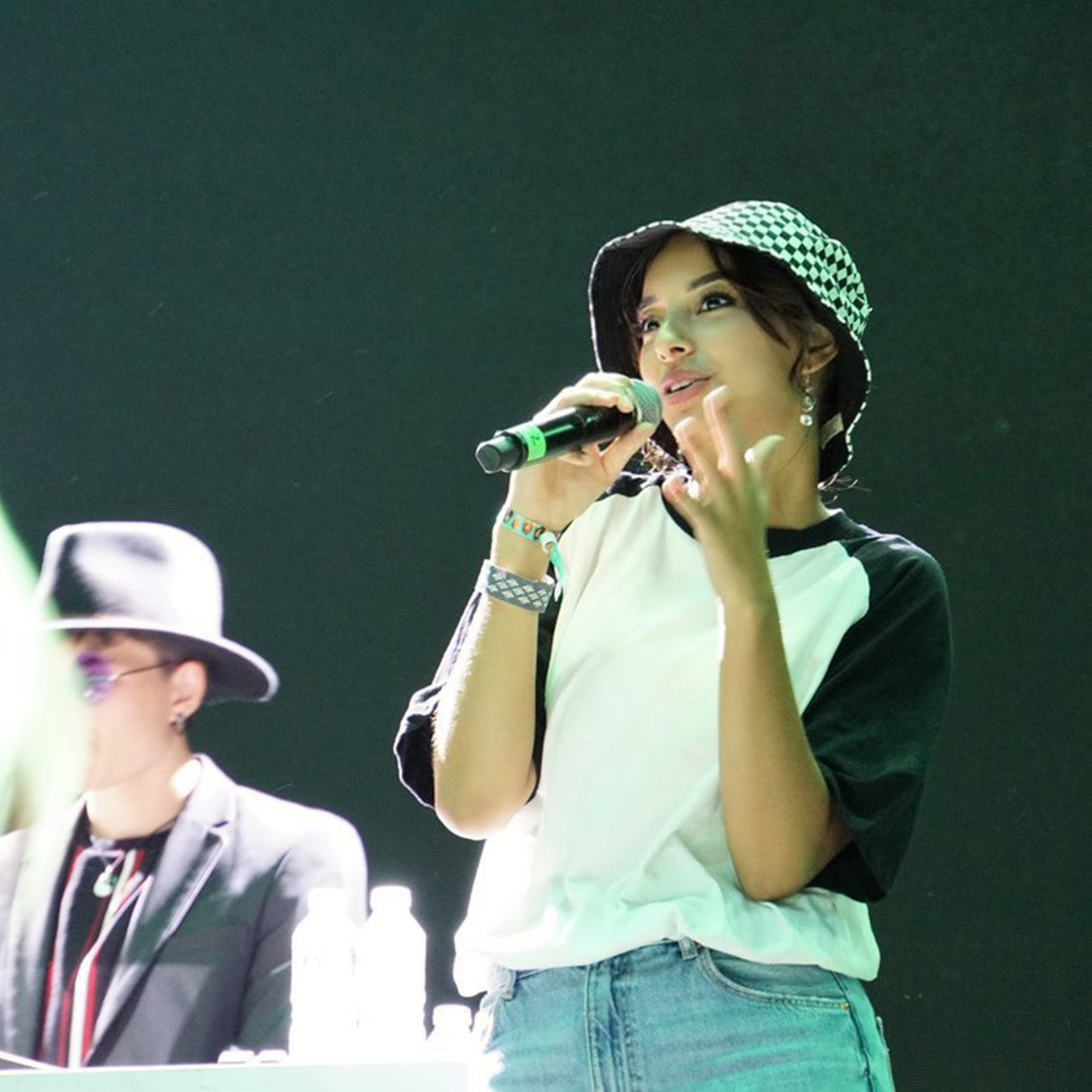

Miss Raisa: ‘Being Muslim is a part of my identity, but not all of it’

The Spanish rapper says hip-hop has given her a platform — but that doesn’t mean she’s the voice of a generation

–

Imane Raisali, 26, Spain’s first female Muslim rapper, walked into her local neighbourhood restaurant in the town of Sabadell, an hour from Barcelona, and the waiter’s face lit up. Tall and radiant, she is the definition of unassuming grace. That is, until she becomes “Raisa”, the defiant star catapulted into the public eye in 2021 when she rapped in a hijab about inequality and intolerance on the popular TV show Got Talent España.

“When I made my first recording at 14, I couldn’t believe it was me,” she said. “I had always been so shy, but rapping helped me to discover who I was.”

“I was criticised, of course, for being part of what was considered a man’s world. But now I see other Muslim girls rapping and it’s great to think each one will get less flack than the last until it gradually becomes normal.”

The first eight years of Raisali’s life were spent in Tangier and Tetouan, Morocco, with her three siblings and her illiterate mother, dependent on the money her father, who worked on fishing boats, sent home from Spain. Six years after the family was reunited in Barcelona’s migrant neighbourhood of Barceloneta, Raisali became fascinated with the rap performed by boys in her class in the school yard. Later, she would be inspired by Lil Wayne, Akon and Eminem, having found refuge in gangsta rap when her father, to whom she was close, died of cancer when she was just 16

“Obviously, I wasn’t going to say the kinds of things they said, but I loved how direct they were. The way they came right out and said what they thought,” Raisali said.

As Raisa, she has become an online phenomenon in Spain with 500,000 followers on TikTok, a platform that recognised her contribution to the fight against discrimination in 2021 with TikTok Spain’s first individual Diversity and Inclusion Award. She gained an even wider audience last July when she decided to remove her hijab.

“I felt used by politicians and some in my own community who were seeing me as representative of Muslim women in Spain,” she explained. “Being Muslim is a part of my identity but it’s not all of it. I’m a lot else besides. I don’t look in the mirror and see Imane the Muslim, or Imane the rapper. I don’t like labels. They just complicate things.”

The hijab move prompted a blizzard of positive headlines in the national press and unleashed a similar volume of vitriol on social media and in person — particularly from members of the Moroccan community.

“Strangers came right up to me on the street and insulted not just my body but my intelligence and said I was a disgrace,” she said. “The sad thing was it came mainly from women.”

‘One of the advantages of growing up between two cultures is that you learn to adapt, and the ability to adapt is what intelligence is about’

The furore only intensified the public anger directed at her a month earlier for her support of LGBTQ+ rights on TikTok when she declared: “You don’t have to be gay to respect the gay community.” At its height, she received a chilling Instagram message describing how one user wanted to behead her. The threat was reported and the author arrested in Madrid in August 2022.

“It was so horrible, it was surreal,” Raisali recalled. “I stand by the values of Islam and I believe in God, but it is a very different God from the one these people believe in. To wish someone dead in the name of God is actually anti-religious.”

Raisali’s journey has given her plenty to rap about. As a child living in Morocco, she struggled with her father’s long absences. When she and her family joined him, she spoke neither Catalan nor Spanish and got by, at first, by playing football with her classmates. Her eagerness to fit in, together with her innate gift for language, meant she was soon speaking both Spanish and Catalan fluently, but she still didn’t feel as if she belonged, often hearing herself referred to as “Moro” – a derogatory term in Spanish for North Africans and Muslims in general.

“I kept thinking, ‘why do you hate me?’ I couldn’t understand the prejudice,” she said. “I didn’t choose to come here. I mean, I was just eight when I arrived.”

It was this feeling that inspired her debut release, Yo No Soy Pero (I Am Not But), which has more than a million streams on Spotify, and states exactly what, as an immigrant, she is not: not in Spain to rob jobs from Spaniards, not ignorant and absolutely not to be pitied.

“One of the advantages of growing up between two cultures is that you learn to adapt, and the ability to adapt is what intelligence is about,” she said. “We live in a polarised world where you’re expected to choose one culture or the other, or you’re considered a traitor. But I’ve mixed things up and I’m happy in my limbo.”

The Catalonia region is home to Spain’s largest Muslim population – almost 600,000 of the 2,250,486 across the country – and Barcelona’s left-leaning mayor, Ada Colau, was the first in Spain to introduce a programme to combat Islamophobia back in 2016, which has since been adopted as the prototype for many other cities across the country.

The programme is run by Barcelona city council’s office for non-discrimination, which has seen the percentage of discrimination cases on religious grounds fall from 3% of the total hate crimes reported in 2018 to 2% in 2021. According to Spain’s National Department for Combating Hate Crimes, Barcelona registered half the number of Madrid’s hate crimes on religious grounds in 2021 despite being home to a larger Muslim population.

“The programme is very well thought out and has become a model not only for the rest of Spain but for Europe regarding the approach to Ramadan and generally developing a closer relationship with the Muslim community,” said Pedro Rojo, co-director of the Islamophobia observatory.

Raisali shares that view. “Ada Colau has always been focused on human rights and allowing all the people in Barcelona a place,” she said.

In December last year, Raisali published her first book, Porque Me Da La Gana. Una Vida Contra Los Prejuicios (Because I Feel Like It. A Life Against Prejudice), which is also the name of her most recent track. The autobiography is a meditation on navigating two very different cultures and coming out on top.

“I’m very against people playing the victim,” Raisali said. “All of us have been the subject at some time or another of discrimination. Who’s to say my experience is worse than yours? “Of course, the discrimination hurts, but you can’t let it paralyse you. You can’t stay marooned in resentment, blaming everyone else. That’s a dead end.”

Now three months pregnant with her second husband, motorbike mechanic Adrian Mattes Sánchez, Raisali is aware that the balancing act she performs between two cultures can be guaranteed to please no one, but against the odds she is still smiling, still gracious. “I have had to deal with so many different things, I have got old before my time,” she laughed.

For Raisali, all her experiences, good and bad, have helped turn her from a timid teenager into a strong, reflective woman with a voice. Even her arranged marriage, aged 19, to a man who referred to music as “the language of the devil” proved instructive.

“I was forever trying to please everyone else, which is why I agreed to it,” she said of the four-and-a-half-year relationship, which gave her Sahar, her four-year-old daughter. “But I don’t regret it. I learnt to express a lot of things I previously hadn’t dared to and I came out of it with a skillset that made me think, ‘OK, now I can cope with anything.’”

The book, like Raisali’s music, packs a punch, reading like a roadmap for Muslims negotiating dual cultures in Spain. However, she rejects the suggestion that she is the voice of a generation. For one thing, it’s another label.

“It’s too much responsibility,” she said. “The book was very therapeutic because I was able to write about things I’d never shared with anyone. A lot of girls send me messages, telling me they identify with my experience, and I appreciate that, but I’m not trying to be the voice of anyone but myself.”

Newsletter

Newsletter