Muslim volunteers are feeding people in need, regardless of their faith

Across the country, mosques and community organisations offer vital support to vulnerable families and individuals

–

It’s been months since Robert, 48, has been able to work. He lost his job in a supermarket after suffering multiple heart attacks, which have left him constantly struggling for breath. Instead of going to work, he attends hospital every other day. Without employment, he was unable to pay his rent. He now lives on £300 a month in benefits and has been moved to temporary accommodation — a small room in a hotel in Thornton Heath, near Croydon.

To feed himself, Robert has sought help from a small group of volunteers at the Alhidaya Croydon Mosque. Every Saturday night, members of the congregation run a food distribution stall, which gives out hot soup and essential home supplies, on a street just off the bustling London Road in Norbury, south London.

On a chilly Saturday evening in November, Robert was among the first customers in line to receive his soup and groceries. He turned up just as the table was being laid out and the first bowls were being served. The stall is usually open for an hour, but after 20 minutes, owing to an increase in visitors, the soup had run out and the last loaves of bread were being distributed.

Robert visits every week to save money on essentials, such as bread and pasta. He’s not alone. As well as groups of unhoused people, there are others who now have to choose between buying food and paying their rent and utility bills. Also among the stall’s visitors were a few community elders, who crossed over from a nearby cafe, and a butcher working a late shift who dropped by for a quick hot drink before returning to his customers.

In London and major cities across the UK, Muslim organisations are setting up food banks and stalls serving hot meals, and delivering emergency food parcels to people in need. Many mosques have done this for some time but, as the cost of living spirals upwards, these services are expanding to meet increasing public demand.

According to statistics published by Islamic Relief in April this year, half of Muslim households in the UK are living in poverty. That compares with just 18% of the general population. British Muslims are being hit particularly hard by the cost of living crisis, but may also have less access to public and community services to support them in hard times.

Recent research found that BME communities were least served by existing emergency support schemes in the UK. The study also found that hesitancy about being seen to need help outside of one’s religious community could be preventing some families and individuals from accessing food banks and other essential services.

Raja Hyder Ali and his wife, Rajabnisha Hajamohideen, have been running the Norbury service for more than five years. Before the pandemic the stall had become a weekend fixture, bringing support to people facing food poverty and lacking shelter as well as providing a meeting point for other community members.

During the period of Covid-19 lockdowns, the kitchen was no longer allowed to serve meals prepared in households by volunteer cooks. As a result, it transformed into a small food bank, sharing basics including bread and tinned goods.

Now, with lockdowns over, inflation and rising costs are driving up demand. Almost a quarter (23%) of Croydon’s residents are living in poverty, and the borough has a child poverty rate of 33%. Among the growing number of people needing help are working families struggling to feed their children and students unable to afford basic necessities by the end of each term.

“It saves money for them because it’s getting so expensive,” Hajamohideen explained. She added that the kitchen also provides a much-needed social experience for isolated individuals: “Some of the people who come here don’t come just to have a cup of soup. They are lonely at home.”

All the food offered is halal or vegetarian, but volunteers also take personal requests from people with other dietary requirements. Tonight, vegan options and gluten-free bread are on the menu.

With the surge in demand for the service, Ali is now in emergency talks with food suppliers including Tesco and Morrisons to see what they can donate to the project.

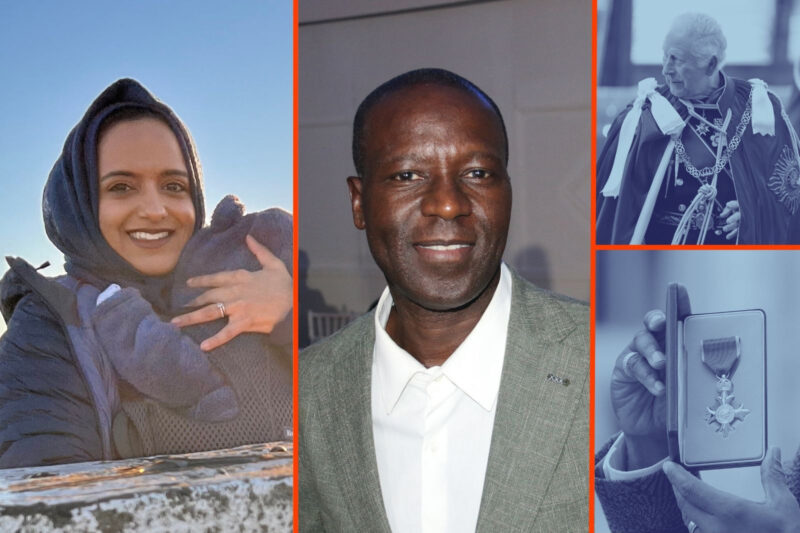

Sadat Hussain is the founder of the Walsall BME Advice and Welfare Centre, a Muslim-led community organisation in the West Midlands. The organisation began providing weekly food distribution for unhoused and hungry people in 2016 and now serves up to 70 people every Wednesday.

Volunteers promote the stall’s location in the city centre on social media, through NHS clinics and by word of mouth. Clients are also referred by agencies such as social services or housing advice centres.

Hussain says that the profile of people being referred to the organisation is changing.

“We’ve already received the message that people in full-time employment are struggling — people who wouldn’t previously have qualified for the service, but now they do. This is a new phenomenon in the last few months,” he explained.

While the Walsall BME Advice and Welfare Centre has an Islamic ethos, its users are mainly white Britons from Christian backgrounds.

“One of our objectives was to promote a better relationship between our communities, between ourselves and others, beyond our heritage,” Hussain said. “We don’t promote our religion. We don’t tell people we are Muslim. They are in need of something and we are providing it; we are providing our service.”

The demographic shift has been noticed at other similar services. In Romford, east London, Zulf Hussain volunteers at a weekly food distribution stall, organised by the Havering Islamic Cultural Centre. A business owner by day, he helped to set up the operation, which provided hot meals for up to 50 people at a time, five years ago.

During the pandemic, the borough of Havering moved many of its poorest and unhoused residents to other areas, where they could be provided with secure accommodation.

The stall now serves around 15 people a week, but Hussain expects that number will soon increase and believes that the service is now more important than ever.

“About a year ago, we could see the cost of living crisis was starting to bite people, so we decided to keep it running,” he said.

Back in Thornton Heath, a final visitor arrived as the tables were being packed away. Beena, an older woman who had travelled a couple of miles by bus to be there, was not disappointed. She stops by every week, but not for the food. Instead, she shows up out of friendship and to support Ali and Hajamohideen’s efforts.

“I have been coming for many years,” Beena said. “I come to see them. They are good people.”

Newsletter

Newsletter