Store cupboard love

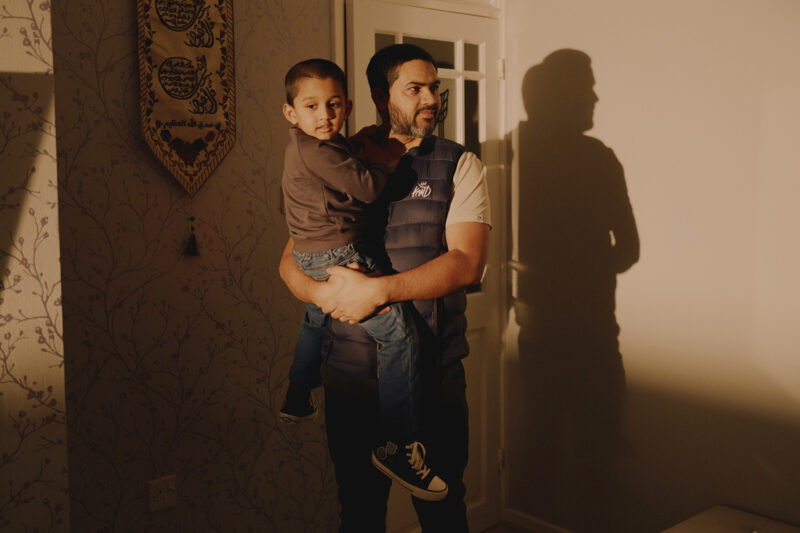

My mother’s stockpile of lentils, chickpeas, cooking oil and treats reaches deep into our family heritage and shows just how much she cares for us all

There is a room in my parents’ cellar that we have nicknamed “Ammu’s bunker”. It contains all the essentials needed by my mother to feed our family for months. Sacks of basmati rice sit beside crates of tinned tomatoes and chickpeas, and five-litre bottles of sunflower oil. There are bags of every type of lentil imaginable. Boxes of Yorkshire Tea are stacked in one corner. Clear plastic storage boxes contain packets of spices, sugar and red cylinders of Saxa table salt. Ammu stockpiles treats too: multipacks of KitKats and Dairy Milk chocolate bars, Green & Black’s for posh days and packets of instant cappuccino powder.

When the Covid-19 pandemic struck, Ammu wasn’t concerned about the panic buying that swept the nation.

“We have plenty in my stores,” she cheerfully assured everyone. “We won’t need to shop for ages.” True to her word, my mother’s magnificent culinary repertoire remained unaffected throughout the long months of lockdown. While the rest of the country went wild for sourdough starters and squabbled over bread flour in supermarket aisles, my parents calmly continued to enjoy their usual meals of steamed basmati rice, lentils tempered with ghee and garlic, and fish cooked in a sour broth with dried mango, thanks to their extensive emergency larder and second freezer.

Ammu is not alone in her habit of stocking up on kitchen staples. A visit to any Asian or “world foods” supermarket will confirm this, with things like chapati flour and cooking oil being virtually impossible to buy in anything less than industrial quantities and turmeric sold by the half kilo, as opposed to the tiny jars found in most shops.

I have often wondered about this tendency toward bulk buying. Is it purely a matter of economy? Doing so is definitely cheaper in the long run and makes sense for large families. It also enables people to have cultural or national staples always on hand and in plentiful supply. For Bangladeshi families like ours, one such ingredient is rice. I remember my dad bringing home 50kg sacks of Tolly Boy long grain rice from the Asian supermarket, which we stored in a black-lidded dustbin in the corner of the kitchen. Our Pakistani neighbours had similarly huge sacks of Elephant wholemeal atta, used to make chapatis.

But there is something else behind it too. I remember chatting about this with a Jewish friend — the first person I had met outside of the Asian community I grew up in, who bought groceries in similar quantities to us.

“It’s the refugee mindset,” she explained. Both of her grandparents fled Germany at the time of the Holocaust. “My grandma stockpiled like this, my mum does, and now I do too.”

She continues to hoard staples — flour, sugar, rice, pasta — in quantities that baffle her partner, but make sense to someone whose family has experienced hunger in living memory.

Recently, I read that Bengal, where my family originates from, suffered no fewer than 31 famines during British rule, the most recent being only 79 years ago. How can those experiences not shape how future generations perceive scarcity and abundance, how they do everything in their power to ensure that their children are never left wanting?

Being able to shop for food at all should be a basic right, but being able to stockpile it for difficult times ahead is a privilege that few are lucky enough to have. The current cost of living crisis, which is only set to get worse, means that thousands in the UK will be forced to choose between heating and eating, despite ardent denials by members of the government. For those people, putting enough food on the table each week is a struggle, let alone keeping any in reserve.

Now, I see my mother’s intentional stockpiling, born from an inherited experience of scarcity, as a powerful form of love. The unsightly rice dustbin that used to embarrass me as a teenager when my white friends came round is a symbol of the resilience of my forebears. The fact that a whole basement room of my parents’ home is now used as Ammu’s store cupboard is a testament to her instinct to protect and nurture her family, and her good fortune in being able to do so.

There is also pride in this store cupboard love. Ammu’s assortment of ingredients is carefully selected in order to make hearty, healthy, comforting meals. Dal bhath — literally, lentils and rice — is a Bangladeshi phrase that is used to mean “food”. It is also what sits at the heart of my mother’s cooking.

One staple dish is kitchuri, which should not be confused with the Anglo-Indian version, kedgeree. First, onions, garlic and ginger are fried in a little ghee, then made fragrant with whole spices: cardamom pods, bay leaf, cassia bark, salt, turmeric and red chilli. Next, washed red lentils and basmati rice are added, in equal quantities, along with vegetables: fresh or frozen green beans and cauliflower, or cubed potato. Hot water is poured over and the pot is left to simmer until the lentils and rice are tender. It is the epitome of home cooking and can always be made from my mother’s carefully curated supplies.

Another standby is egg bhuna. Eggs — which Ammu always has plenty of — are boiled, peeled and left to cool while a spicy masala is made. Onions and garlic are sauteed until soft and golden. Turmeric, salt and a sprinkling of tandoori powder are added and fried for another minute or so. Next, a couple of diced tomatoes or half a tin of chopped tomatoes go in, then the mixture is left to bubble on a low heat until it becomes silky and unctuous. Finally, the eggs, scored lightly with a knife to allow the flavours to penetrate, are added to the pan and coated in the sauce. Chopped fresh coriander or mint is scattered over the top and the dish is served with plain boiled white rice.

When I was a child, I used to hate this meal because it meant that either my dad hadn’t managed to get to the shops, or my mum was feeling tired and uninspired. Now, I am awed and humbled that, for my parents, convenience food was still always nutritious and home cooked.

A final family favourite is sardine sathni. Every British-Bangladeshi has their version of this dish, from which the English word “chutney” is derived. It is also known as a bhortha — beautifully explained by the British-Bangladeshi food writer Dina Begum and recently popularised by Nigella Lawson and Ash Sarkar. This simple, no-frills dish always includes onions, chillies and coriander, but the choice of fish is limitless, from North Sea cod and imported Bangladeshi rohu to frozen fish fingers.

Finely sliced shallots are fried until almost crunchy, then a couple of tins of your chosen fish are added to the pan, along with sliced green chilli, salt and turmeric. The mixture is cooked on a medium heat until it crisps and chars in some places. A good squeeze of lime juice and handfuls of freshly chopped coriander are added at the end. Served with dal and white rice, it is the definition of comfort eating. Needless to say, Ammu’s bunker contains stacks of tinned sardines, mackerel and tuna — and, writing this, I’ve realised that my own pantry now looks remarkably similar.

Newsletter

Newsletter