Hamlet establishes Riz Ahmed as one of the greats

This modern retelling enhances the cruelty of Shakespeare’s tale, infusing the terrible fate that awaits our protagonist with societal anger

There is no shortage of Hamlets in the world. The play has been dissected, modernised, deconstructed and reassembled so many times that any new adaptation arrives carrying a heavy burden of justification. Why this Hamlet? Why now? What more is there to say?

Riz Ahmed answers those questions through stunning performance. His Hamlet, now out in cinemas, may not reinvent Shakespeare’s tragedy, but it delivers a version that feels urgent and anchored by Ahmed’s central turn in the titular role — reason enough to justify its existence.

From the opening scenes, Oscar-winner Ahmed moves with a sense of purpose and further establishes himself as one of the greats. From his start in Chris Morris’ Four Lions to his mindblowingly brilliant turns as a deaf drummer in Sound of Metal and rapper in Mogul Mowgli, he has brought a Shakespearean weight to all his work.

To see him turning his talents to what is widely considered the world’s greatest of texts feels inevitable. This is a marriage made in heaven, yet this performance is not a reverent Hamlet designed to further preserve the text in amber. It pushes forward, treating the story as something to be inhabited for all its rich humanity rather than eulogised from a distance.

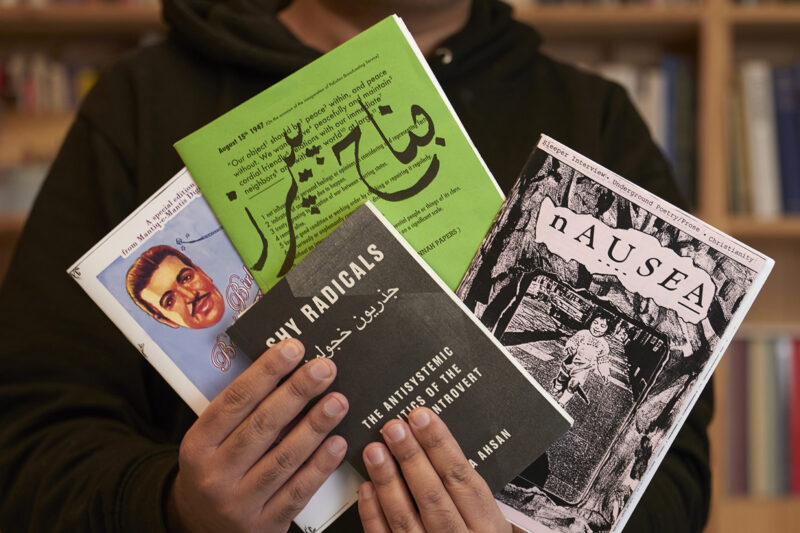

Ahmed has said he’s always wanted to gift the world his Hamlet, that his connection to the text has meant this adaptation was years in the making. With its modern London setting and South Asian casting, there is a new layer that comes with the story. The modernity enhances the cruelty of the tale, infusing the terrible fate that awaits our protagonist with societal anger.

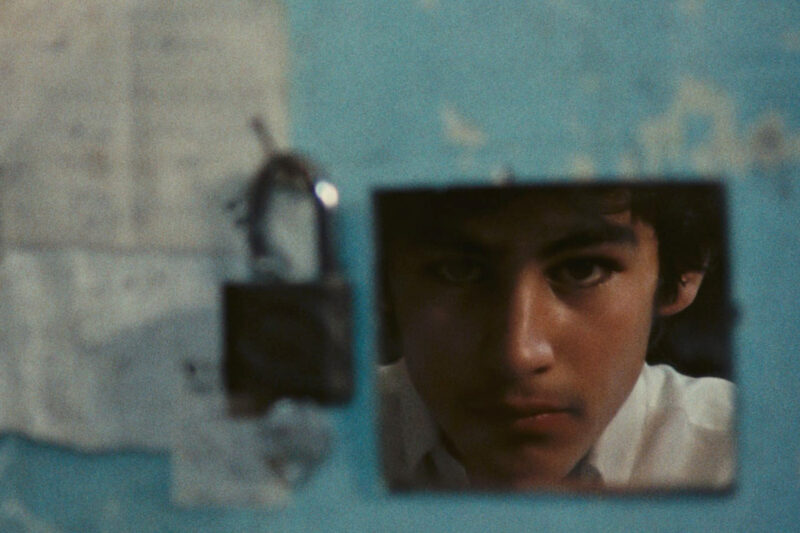

The beginnings of the film crackle with an unpredictable energy, driven by a film-making flair from Aneil Karia, who previously collaborated with Ahmed on Oscar-winning short The Long Goodbye. Karia’s approach favours immediacy and emotional electricity. For audiences who have slogged through Shakespeare adaptations on stage and screen, this is a refreshing elixir.

That directness finds its clearest expression in Ahmed’s performance, jolting the text alive like Frankenstein’s monster infused with lightning. His Hamlet is restless, volatile and intensely present, a man whose intelligence and grief fuels his agitation rather than paralysing it. There is a physical urgency that makes Hamlet’s internal thoughts feel dangerous, as though every realisation risks tipping him further into fury. It’s a gripping interpretation that pulls the character out of abstraction and plants him firmly into a deteriorating body.

In the first half, scenes are given enough room to breathe, and the camera stays attentive to Ahmed’s shifting emotional register, even in moments of silence. A standout wedding dance sequence exemplifies what Karia’s film does best: it blends spectacle with psychological unease, allowing celebration to curdle into something threatening and unstable. In moments like this Hamlet feels genuinely alive, committing fully to the text’s emotional specifics.

As the film moves on, its momentum accelerates as we speed towards the inevitable bloodbath. The relatively brief runtime for a Hamlet, coming in under two hours, means the story begins to move at an unnerving pace. While this compression limits some of the play’s emotional density, it also gives it a clarity of purpose given we all know where it’s going. Rather than becoming mired in repetition or excess, the adaptation remains focused, guiding viewers steadily toward its cruel conclusion.

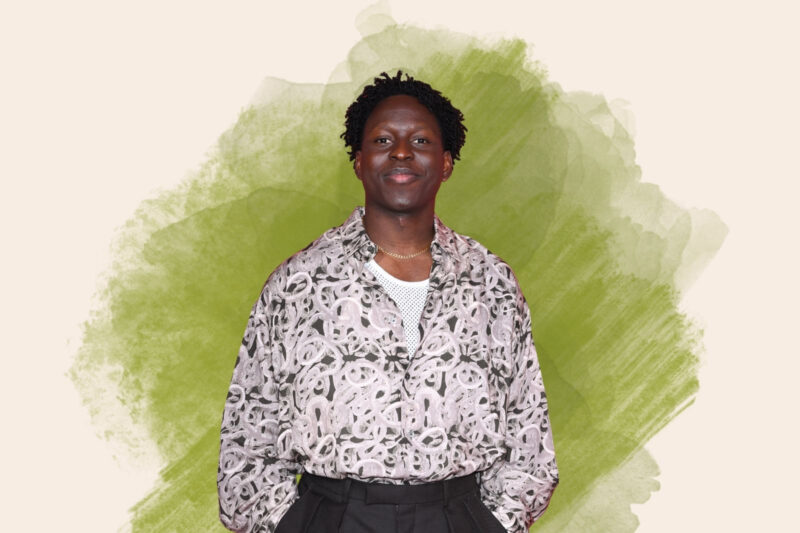

Crucially, the film never loses its grip, thanks to the strength of its performances. Sheeba Chaddha’s (Badhaai Do, Gully Boy) Gertrude adds further weight to the film’s later stages. As the consequences of her choices come into focus, Chaddha delivers some of the most affecting moments. Her performance is restrained and quietly devastating, offering a counterbalance to Ahmed’s volatility.

Stuart Bentley’s cinematography maintains a stark, controlled beauty throughout, favouring clean compositions and an understated palette that suits the story’s emotional severity. A particularly haunting final image lingers long after the credits roll, underscoring the film’s aesthetic confidence and sense of restraint.

This Hamlet doesn’t solve Shakespeare’s most famous problem — how to avenge your legacy without ultimately destroying it — but it makes the tragedy feel immediate without flattening it entirely. Many contemporary audiences encounter Hamlet less as a text than as a cultural monument and this version works deliberately to lower the barrier to entry. Its emphasis on performance, momentum and clarity makes it an accessible point of engagement, particularly for viewers who might otherwise feel intimidated by Shakespeare on screen.

There is, inevitably, a sense of familiarity in where the story ends. Hamlet remains Hamlet, and the conclusion arrives as it always does. But Ahmed’s version earns its place through conviction. It knows what it wants to be: a focused, performance-driven adaptation that privileges emotional immediacy over exhaustive interpretation.

Newsletter

Newsletter