The teacher who gave me the confidence to be a writer

Our education system is judged by exam results and inspections, but its greatest achievement will always be inspiring children and transforming young lives

My clearest memories of year 7 English lessons are not of Shakespeare or grammatical rules. Instead, they’re of paper-ball fights, puerile jokes and the lucrative business I’d built up selling sweets to other kids. I was not a well-behaved student. I was often on report for bad behaviour, carrying around a booklet that needed signing at the end of every lesson. I stormed out of classrooms, argued with teachers and was suspended for fighting. I was an immature boy, far more interested in who was the toughest in the year than who was the smartest.

At my all-boys state comprehensive in Luton, we had our own system for classifying teachers. They were either strict or “safe”. Safe meant kind, patient, unlikely to shout. Miss Fielden was firmly in the safe category. She was passionate about her subject and somehow managed to tolerate a room full of restless, chaotic boys who tested her limits daily.

For all the fond memories, I regret not taking her classes seriously enough. I didn’t read anywhere near as much as my brother. It felt like a chore rather than a pleasure. And, yet, I was drawn to writing. My imagination ran constantly. I made up elaborate stories in my head. Occasionally, I would write them down — half-formed ideas, scribbled in notebooks or typed on an old computer at home.

By year 8, my grades had started to slip. The school intervened and I was given after-school tuition every Tuesday, one-to-one support with Miss Fielden. I still remember sitting in classroom B8 as she asked me a simple question: what did I like about English? I told her I liked to write.

I explained that I was working on a science fiction story at home. It was an ambitious, slightly ridiculous mash-up of Doctor Who and Harry Potter, drawing heavily on hollow earth theory, the idea that there is life beneath the Earth’s surface. At the time it felt entirely original to me.

Instead of dismissing it, Miss Fielden encouraged me. She asked me to bring in drafts. Every Tuesday, I handed over my latest attempt and she would read it carefully, offering feedback that was honest but never crushing. She treated my writing as something worth taking seriously. That alone was transformative. She even encouraged me to enter for the Young Muslim Writers’ Awards.

From that point on, my relationship with English changed. I paid attention and tried harder. My grades improved and it quickly became my favourite subject. Miss Fielden taught me for five years and watched me grow up, not just academically but personally. She encouraged my interests beyond the curriculum. When she realised I was drawn to current affairs, she urged me to explore that, through my speaking assessments and the choices I made outside the classroom. In the end, I received an A* in my English language GCSE. Knowing my politics at the time, she pointed out that I had beaten most of the kids at private schools.

As I get older, I think more and more about the role teachers like Miss Fielden play in our lives. At a time when schools increasingly resemble exam factories, that kind of care matters. She was concerned not only with my grades, but with my future.

When I left school, she wrote me a note that I have kept ever since. “Dear Tajjamal,” it read. “For you I have but one word: write. For everyone else I have three: vote for Tajj! Believe in yourself, young man. I do. Wishing all good wishes for the future. Helen Fielden.”

I did go on to write. I have just completed the manuscript for my first book, Come What May We’re Here To Stay: The Story of South Asian Resistance in Britain, which will be published later this year.

It took years of archival research, oral history interviews, endless transcribing, writing and rewriting. In 2023, Miss Fielden got back in touch to congratulate me on winning a Royal Society of Literature award for authors engaged on their first commissioned works of non-fiction for my forthcoming book. She sent a card and donated to a charity in my name.

Still, there were many occasions where I doubted my ability to write a whole book. Should I have waited a few years to hone my skills? Had I done enough research? Would I ever get round to finishing it? It was a demanding, often exhausting process, but it’s finally done. When the self-doubt crept in, as it often did, I thought about that note.

Growing up, I did not know any authors, historians or journalists. As is the case for many working-class kids, we had no family connections, no informal mentors, no obvious pathways into those worlds, dominated by the wealthy and privileged. Even when we do enter them, we are often made to feel like outsiders.

That is why good teachers matter so much. They encourage us to dream big, pursue our passions and instill in us the confidence and self-belief to get there.

As I wrote in 2025, teachers increasingly act not only as educators, but as administrators, counsellors, psychologists and social workers. They do all of this on top of already overwhelming workloads, for pay that rarely reflects the responsibilities they carry.

They should not be expected to go the extra mile. But, in my experience, many do. In doing so, they transform the lives of young people. For working-class children, teachers are often among the only mentors we have. They can open doors simply by making us believe that they exist.

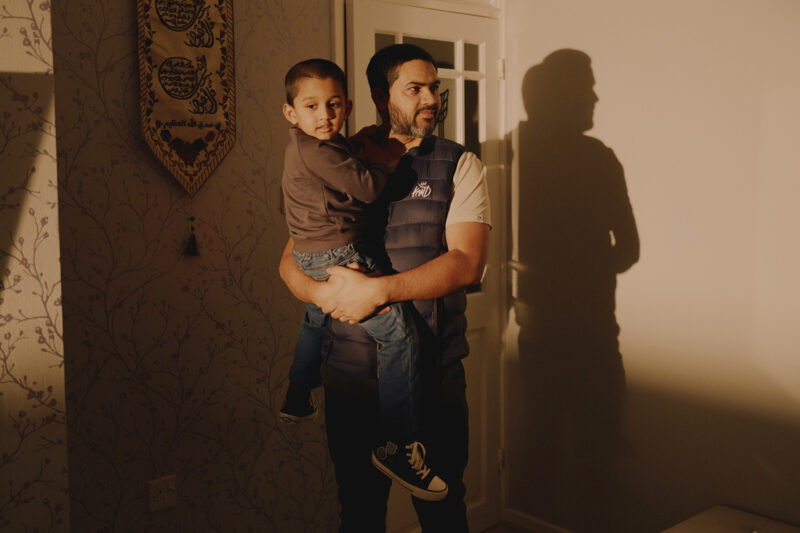

I met up with Miss Fielden last week. It was the first time I’d seen her in more than 10 years. She was providing backing vocals for a rock band at a gig in aid of Luton Foodbank.

It was incredibly rare for a class to have the same English teacher for five full years, but Miss Fielden told me it was a deliberate strategy.

“Your class was a bit of an experiment,” she told me. “I wanted to build a relationship with my students and their parents.”

The experiment clearly worked.

I asked some friends about their recollections of her recently. “She believed in all of us,” said one. “She was very much invested in my personal growth, parents’ evenings with her felt much more personal to my future than a generic report of my behaviour and grades.”

“We had to put down the name of a teacher we could trust and confide in during form time and I put hers down because of the person she was to us,” recounted another.

Miss Fielden treated us like equals. She spoke to us like adults. And, crucially, she believed in us. That’s something that stays with you for life.

Newsletter

Newsletter