Prioritising UK medical graduates like me will not fix the NHS

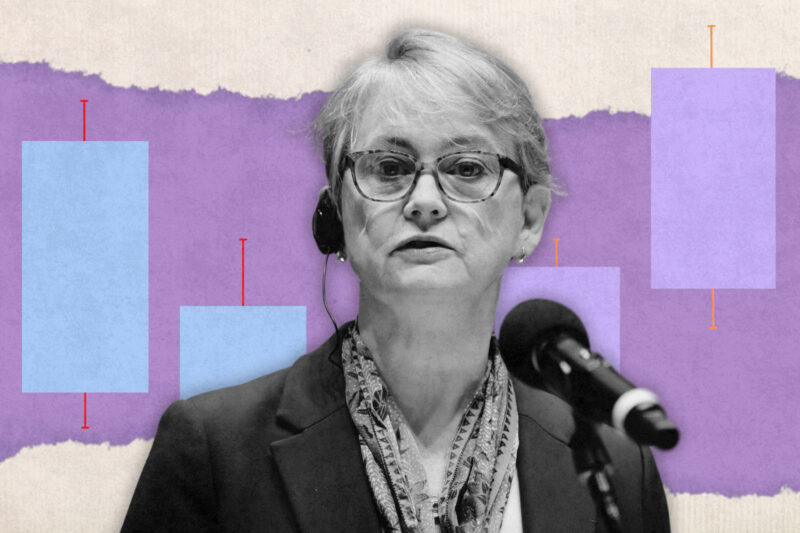

The health secretary, Wes Streeting, has announced plans to put British-trained doctors at the front of the queue for crucial speciality training posts

Wes Streeting has boasted that he is “cleaning up” a “Tory mess” with his latest reforms to the NHS: prioritising British medical graduates over their international colleagues for speciality training posts. These posts are crucial for resident doctors to secure and advance their careers; despite the many years doctors spend at medical school, medicine is an increasingly precarious field.

Naturally, many British doctors have celebrated the decision, which acquiesces to demands made over the past year by the British Medical Association doctors’ union. But the policy creates more problems than it currently solves.

It is true that the current situation is untenable. Once a newly graduated doctor completes their first two years as a foundation doctor, they are eligible to apply for speciality training. Interest in these posts has become extremely competitive in recent years. Applications for general practice (GP) or psychiatry, for example, averaged around two per post in 2020. By 2025, those figures had risen to five applicants for every GP post, and a whopping 21 for every psychiatry post.

As a UK-trained resident doctor, I understand the annoyance many feel. It seems nonsensical that, after seven years of training, we still face a significant risk of unemployment, given that job stability was previously one of the few perks of the profession.

Many of us currently work in “locally employed” jobs — non-training posts in a particular speciality that are used to fill gaps in rotas. These posts offer no career progression and stagnant wages. They are brutal to work in.

In years gone by, we could have relied on fellowship posts and locum shifts to pay the bills, but these too have dried up owing to competition.

In short, getting a training post is essential.

In the past year, 15,723 UK-trained doctors applied for speciality training, alongside 25,257 overseas doctors. These 41,000 applicants were competing for only 12,833 posts. And that bottleneck is worsening — there have already been 47,000 applicants for training places in 2026, although the NHS has not yet announced how this figure breaks down into UK-trained and overseas doctors.

It may seem, then, that the answer for doctors trained in Britain is simple: prioritising them for these places will reduce their risk of unemployment.

But this doesn’t tell the full story. The example of GP training — a field that historically has had the highest number of available posts — is instructive. In 2024, the last cycle for which full data is available, 5,538 doctors who had trained in Britain applied for places, compared with 17,146 internationally qualified candidates. There were 4,096 places available. Yet only 2,053 international applicants had a GP post accepted, compared with 2,332 British-trained graduates. So British graduates are already significantly outcompeting international graduates by some margin.

A similar policy had been in place until 2020, when the demands of the health service saw the playing field between British-trained and overseas doctors somewhat levelled. It is not as if demand for doctors has decreased since then. Does it really make sense to return to this arrangement and make international doctors the pariahs of the workforce?

While British doctors can at least find some limited work doing temporary locum shifts if all else fails, anything short of a full-time post leaves migrant doctors at risk of visa loss — something my own international colleagues are concerned about. While I worry about securing my own training post, I do not have the additional fear of being forced to leave the UK, or of being overlooked not because of talent but because of country of origin.

Nevertheless, the policy is set to be fast-tracked through parliament and could be in place by the end of the current session. If the bill makes it through in time to influence those 47,000 applications for training in 2026, the only group of migrant doctors who will be treated equally to their British-trained counterparts are those with indefinite leave to remain, which requires them to have been in the UK for five years.

This will help few, as the large increases in medical migration have occurred only in the past five years — since Covid, when Britain desperately looked to the world to support its anaemic workforce. The biggest occurred in 2024, when 20,000 joined the register.

From 2027, an even more select group of overseas applicants will make the cutoff: those with “significant experience”, which is as ambiguous as it sounds, kicking the details further down the road.

In my opinion, the policy is being rushed through, perhaps to hinder the chance of strike action, or to appease the voters that Labour is losing to Reform. The real-life consequence is that migrant doctors are left questioning their position in the workforce, and their career in Britain as a whole.

The irony is that Britain does need more doctors. The UK has 3.2 doctors per 1,000 people; Germany has 4.5. We haemorrhage about 4,000 doctors a year to countries such as Australia and New Zealand, where British-trained doctors go in search of better working conditions and pay. Every day, I hear from patients about their struggle to see a specialist or to get a GP appointment. If the government wanted to be truly aspirational, it would increase the number of training posts and subsequent consultant and GP posts available to meet demand.

As a medical student, I was regularly fed the line that the NHS is a meritocracy for those who work in it. Yet years of evidence show that race, gender or class will affect your career significantly. This policy is just another example of moving the goalposts to benefit one group over another, without dealing with the real issue at hand.

Newsletter

Newsletter