How an exclusive Alpine retreat taught me to put myself first

I confronted my generational guilt and learned that rest and self-care are no longer optional indulgences, but essential tools for life

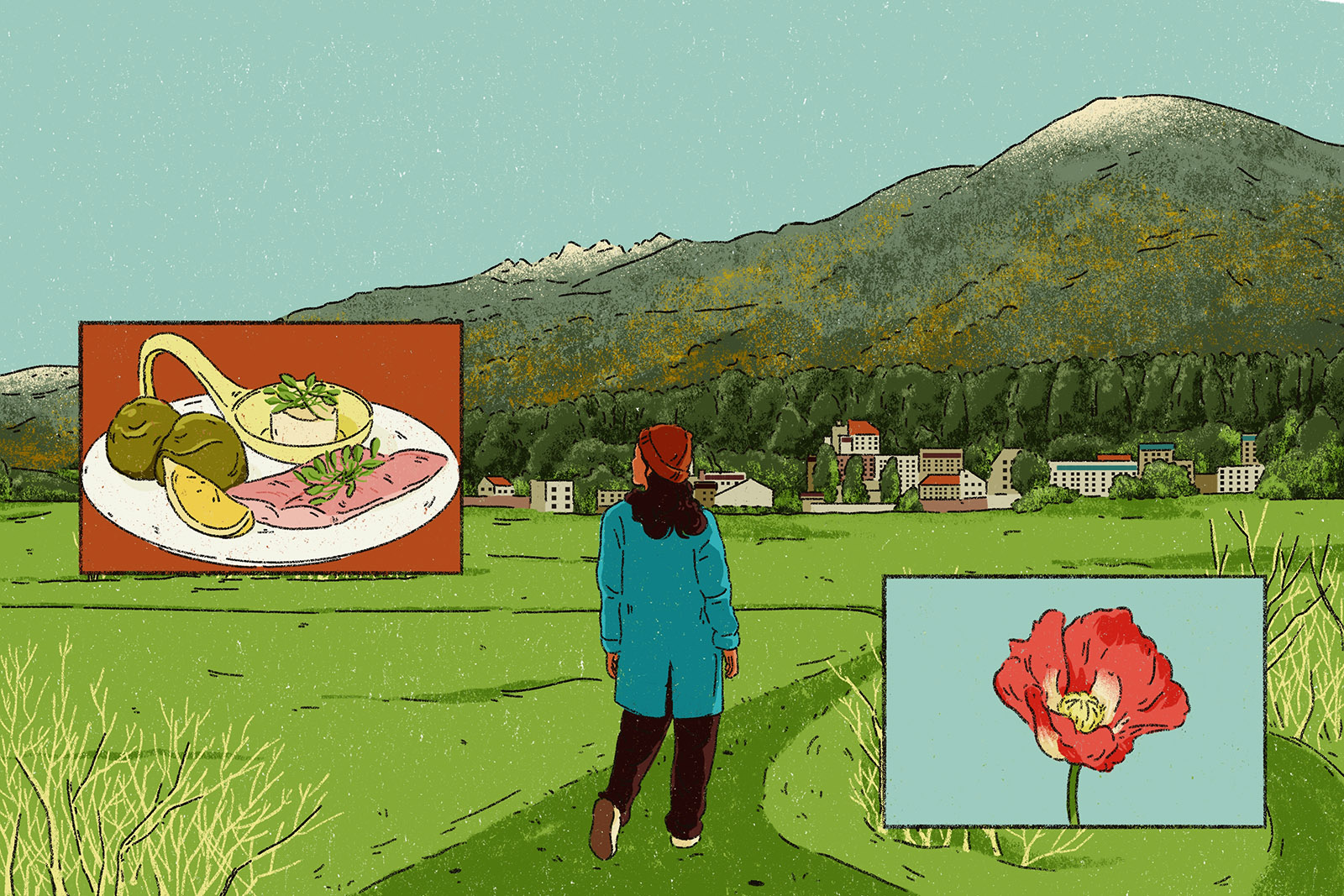

It’s a sunny November afternoon in Igls, a small village perched on the slopes surrounding the Austrian city of Innsbruck. Undulating fields spread in all directions, with snowcapped mountain peaks rising in the distance.

I’m on a group walk organised by Park Igls Medical Spa Resort, where I’ve been invited to stay for a week to take part in its De-Stress burnout prevention programme. With me is an older gentleman from Liechtenstein, a tall blonde woman in her 40s from Germany and the hotel guide.

As we turn a corner, heading uphill into a patch of forest, the woman asks me where I’m from. “London, but my family are originally from Afghanistan,” I reply.

It’s a detail I’m always sure to mention. My parents both left Kabul before they were 18, following the Soviet invasion of 1979. All my immediate family, on both sides, were displaced. The least I can do is not forget my heritage.

During one of my scheduled therapy sessions the next day, I tell the psychologist about my parents’ work with the Afghan community in London. I share my admiration for what they have done in the four decades since they became refugees.

Afghans are typically generous — hospitality is an integral part of our culture — but my parents took this to another level, making little distinction between the home and the community. Even as a toddler, I accompanied them to conferences and events they hosted for London’s Afghan diaspora. While I couldn’t be more grateful for the values their dedication taught me, it also left little space for emotion or personal needs within our family. As a result, I became the emotional caregiver to my parents and younger sister from an early age.

My parents still put themselves last. If they receive a late-night call from someone in need, family or a stranger, they drop everything. I believe that being among the first lucky ones to flee Afghanistan has fuelled this sense of obligation towards others. I understand the motivation, but it also saddens me. I wish they would take better care of themselves, because prioritising my own needs is now often accompanied by a deep sense of guilt.

When I first arrived at Park Igls, I was dazzled by the general air of peace and tranquillity, the size of my suite and the five-star facilities. My treatment plan included three full-body massages, two talk therapy sessions, three medical examinations and an array of other treatments.

But a voice kept creeping into the back of my mind.

“You haven’t earned this. Other people are more deserving,” it told me. “You’re not helping anyone by being here. This is self-indulgent.”

The fact that the spa’s other clients were all of a different age, race and socioeconomic bracket to me only heightened that feeling.

“There’s a really uncomfortable relationship with rest that often comes up among second-generation individuals,” says counselling psychologist Dr Thanh Luu, who was born in Germany to Vietnamese refugee parents. “Joy and rest often bring the most guilt because we’ve been trained to be good at suffering and to work through tiredness and hardship.”

Luu goes on to add that “the parenting role often falls to eldest daughters, or daughters in general. You lose your role as a child, but you’re also not a proper parent. You’re essentially left in no man’s land. It’s completely alien for someone in that position to look after themselves. When they do, that’s when the guilt kicks in.”

This phenomenon, common among the children of refugees and immigrants, has recently been named as thriver’s guilt. It is directly connected to our access to opportunities not enjoyed by our parents and typically involves feelings of unrelenting pressure to succeed, to always be happy and to never waste either time or resources.

Those perceived demands often make you take on more than you should and lead you to view rest and self-care as optional and sometimes even unsafe.

Attending what the Times described as 2025’s best detox spa, on a week-long complimentary programme that usually costs around £4,000 in total, while my parents won’t even let me book them a birthday massage, seemed like the ultimate act of frivolous excess.

Before flying out to Austria, I had seen a private therapist to unpack some of those feelings. In the end, though, it was the psychotherapy sessions at Park Igls that brought me to a sense of acceptance regarding my relationship with my parents. It also helped me to understand a separate traumatic childhood experience.

As the days passed, I started to feel more comfortable and settled at the resort. It was refreshing to be in such a health-conscious environment. I allowed myself to enjoy it and acknowledged but didn’t dwell on feelings of guilt.

I established a routine, making the most of the third-floor fitness centre, the pool, sauna and massage therapies. I also enjoyed getting to know the staff and other guests.

One afternoon, I explored Innsbruck with the German woman I’d met on the walk. Another evening, I had tea with the man from Liechtenstein, finding out that his first wife was Muslim and that, like my own husband, his godson had converted to Islam.

The assumptions I had made when I first arrived — that I would have little in common with my fellow attendees — faded. My interactions with them also reminded me why I love to travel. There’s something sacred about connecting with someone from a completely different background. It’s like all the surface-level labels we use to define ourselves melt away and it’s our souls that are meeting.

I also enjoyed learning more about the resort’s philosophy, which is based on Mayr medicine, a holistic health approach developed by an Austrian doctor named Dr Franz Xaver Mayr. It centres on gut health as the key to overall wellbeing. Like all the resort’s treatment plans, my programme was anchored by the six pillars of cleansing, rest, education, substitution, exercise and self-discovery.

Though Mayr medicine is an alternative therapy and some of its practices lack conventional scientific backing, I noticed that several aspects align with Islamic traditions, with fasting being the most apparent. In the same way that Muslims limit food during Ramadan as a form of physical and spiritual purification, the Mayr method encourages rest of the intestinal tract through a made-to-measure dietary plan.

I started my week on diet level 2, which consists of one or two cups of “Mayr food”, such as low-fat yoghurt or lactose-free milk, a small bread roll and 50g of protein per meal.

The portion sizes were challenging, but we were advised to chew slower and more thoroughly, which creates the feeling of being full faster and takes pressure off the digestive system.

It reminded me of a hadith, in which the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) says: “No man fills a container worse than his stomach. A few morsels that keep his back upright are sufficient for him. If he has to, then he should keep one-third for food, one-third for drink and one-third for breathing.”

In this age of overconsumption, I’m grateful to belong to a faith that prescribes moderation and an annual review of one’s attachment to food. Like Ramadan, my time at Park Igls made me confront how lucky I am to have never faced food scarcity.

The retreat also forced me to challenge my discomfort with being looked after. Now, rather than feeling guilty for what was never in my control, I’m determined to honour my privilege, to benefit others and to recognise my own limits.

I plan to continue therapy and have upgraded my exercise routine to include higher-intensity strength and endurance training. I’ve also updated my personal fasting plan, with an earlier first meal, more mindful chewing and smaller portions.

But, above all else, I want to keep prioritising the practice of my faith. My salah forces me to sit with myself five times a day. The prayer mat is one of the few places I can fully let go of control and find a sense of peace.

On my last morning at Park Igls, I had my final medical examination with a doctor I hadn’t encountered before. During the abdominal check, he saw the outline of Afghanistan I have tattooed on my arm and asked which country it was.

When I told him, he said he had several Afghan patients at his practice in Innsbruck and spoke highly of them. I immediately warmed to him. Afterwards, he told me about how he had been searching for the meaning of life at 18 years old and that God had answered him in prayer.

“God is always there, ready with abundant love and wisdom. We need only be receptive to it,” he told me. “I pray that God protects and guides you towards His love.”

My heart sang in response to his words. I felt the divine love he spoke of and was compelled to give him a hug. And, instead of guilt, I felt grateful, for both the novelty of the experience and for putting myself first.

Newsletter

Newsletter