‘Forwarded many times’: the false health hacks shared through family WhatsApp groups

From group chats sharing holistic ‘cures’ to medical myths, why are minority communities disproportionately affected by health misinformation?

“In just 24 hours knee pain completely disappears and your skin becomes younger!” reads a thumbnail of a Farsi-language YouTube video sent to a group chat on WhatsApp. Titled simply “cures”, my mum, a couple of aunts and eight other distant relatives use the chat to send each other a steady stream of holistic “discoveries” and health hacks. It’s one of many similar groups she’s a part of.

The content comes in various forms: YouTube, TikTok and Instagram videos or voice notes of unknown origin that have been “forwarded many times” on WhatsApp. The common thread running through it all is a mistrust of the medical establishment and the idea that certain knowledge is being purposefully kept from you.

“The pandemic was a massive turning point within healthcare — there were the false cures for Covid-19, the herbal miracle treatments, and then the misinformation around the vaccine,” says Dr Shehla Imtiaz-Umer, national director for advocacy for the British Islamic Medical Association and a GP who specialises in making healthcare more inclusive.

Research has shown that people from ethnic minorities are disproportionately affected by health misinformation disseminated across social media, leading to lower rates of vaccine uptake and higher rates of infection and mortality. Imtiaz-Umer, who is involved in outreach work on vaccines, notes that often the misinformation is tailored to each community’s specific anxieties or concerns. For Muslims, one of the most prevalent myths was that the Covid-19 vaccine was made from dead foetuses or haram ingredients.

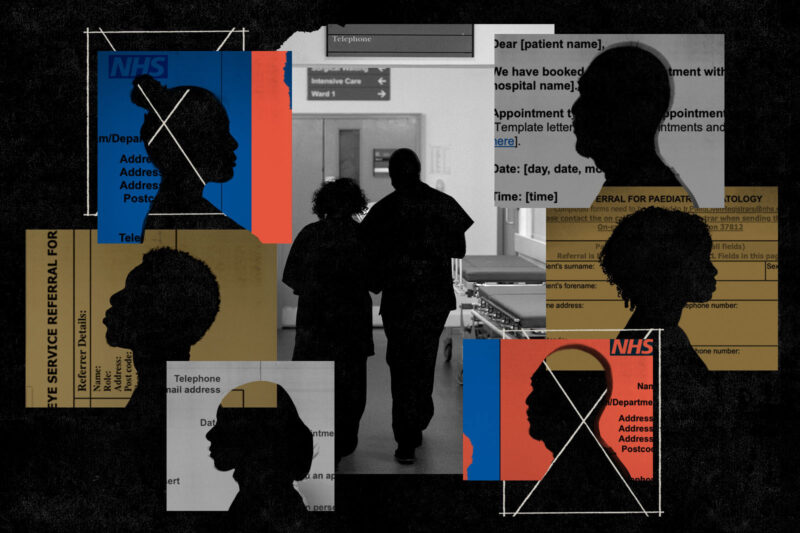

Imtiaz-Umer is, however, sympathetic to the underlying reasons why people from racialised communities may turn to these harmful sources for health information. A survey released this year revealed “alarming” levels of distrust of NHS primary care givers among Black, Asian and ethnic minority patients, largely because of prior experiences of discrimination. The NHS Race and Health Observatory has previously found “overwhelming” evidence of poor health outcomes for these groups.

“Historically, the specific needs of marginalised communities are not recognised or helped by medical systems, or even by societal systems. Layer that with barriers to mainstream or official sources for healthcare information — whether that’s in terms of language, literacy or accessibility — and you’ve got the perfect environment for the proliferation of this kind of misinformation,” Imtiaz-Umer explains.

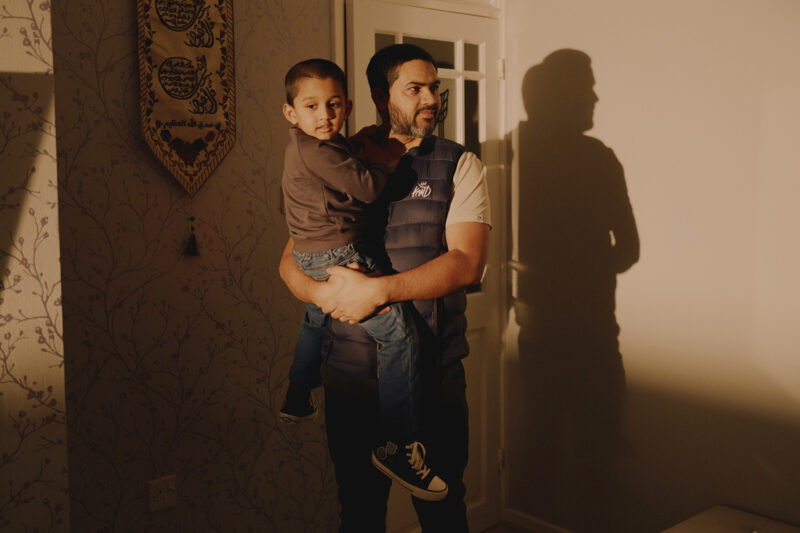

“When you’re getting these forwarded messages from trusted friends, family members or people from the community that are linked by faith, then that often will hold more weight than medical information from people that you have a natural mistrust towards.”

Imtiaz-Umer calls for investment in community workshops run by healthcare professionals to teach people how to critically analyse the information they see online. She also recommends taking a trusted person along to medical appointments as support.

Iman, who asked to remain anonymous, is an artist of Kurdish descent based in the UK. She says her mother regularly sends misinformation on everything from vaccines to colloidal silver over group chats. “I think she sees this as doing her due diligence,” Iman says. “There’s an idea that if some information exists in the world, that it’s important to first of all assume that it’s not true, and secondly, find some kind of alternative. The further from the original piece of information that alternative is, the more true it feels — as if someone has ‘unveiled’ the truth.”

A 2014 study looking at the effects of medical conspiracy theories on the general population in the US found that belief in such ideas correlates with “a greater use of alternative medicine and the avoidance of traditional medicine”. Post-pandemic, it’s a mindset that has become increasingly commonplace.

Thea Khan, a British Pakistani creative director from London, says that the pandemic was a catalyst for the normalisation of this type of content within her own family group chat, which includes around 20 relatives. “Pre-Covid, it was just family updates and pictures. During Covid, it began to turn into this fake news dumping ground,” she says.

WhatsApp has taken some measures to tackle misinformation, such as restricting the number of times content can be forwarded, and outlines advice on its website on how to prevent its spread. Meta Platforms did not respond to Hyphen’s request for comment.

Khan hopes the information shared on her family group chat won’t have any negative effects. “The whole of my mum’s side is obsessed with health and they get really competitive about who is the most healthy or most up to date with health information. The platforms that they’re getting the information on — Facebook and Instagram — promote more of these alternative sources. It’s almost like sharing anything from the NHS is too obvious.”

Yasir Sacranie, an NHS pharmacist, regularly receives misinformation that’s been forwarded in his own WhatsApp group chats. He is the founder of Micropharm, an online platform designed to make pharmaceutical education more accessible, including training on how to combat misinformation with facts.

“A lot of people use social media to consume content. We’re trying to meet people where they are, and hopefully you drown out the misinformation by having so much reliable information around about it,” he says.

“I work in an inner-city area with lots of ethnic diversity and we come across the impact of misinformation and disinformation all the time. There have been challenges in terms of trying to get the most deprived patients from different minority backgrounds to take up vaccines,” says Imtiaz-Umer. But the harm isn’t confined only to vaccines.

“We’ve had patients who have had a cancer diagnosis and refuse medical treatment, wanting to go down the herbal cure route. Unfortunately, when they’ve changed their mind, it’s been too late.”

Beyond the health dangers, consuming this content also brings risks of social isolation and distance between loved ones.

“It impacts all our conversations, because I feel like I can’t express any of my real worries about the world,” says Iman, adding that many of her mum’s friends have distanced themselves from her because of her beliefs. “We could be out and looking at a gorgeous day — I’ll see a blue sky and she sees chemtrails.”

Newsletter

Newsletter