Streeting’s fight with doctors could win him headlines but cost him his legacy

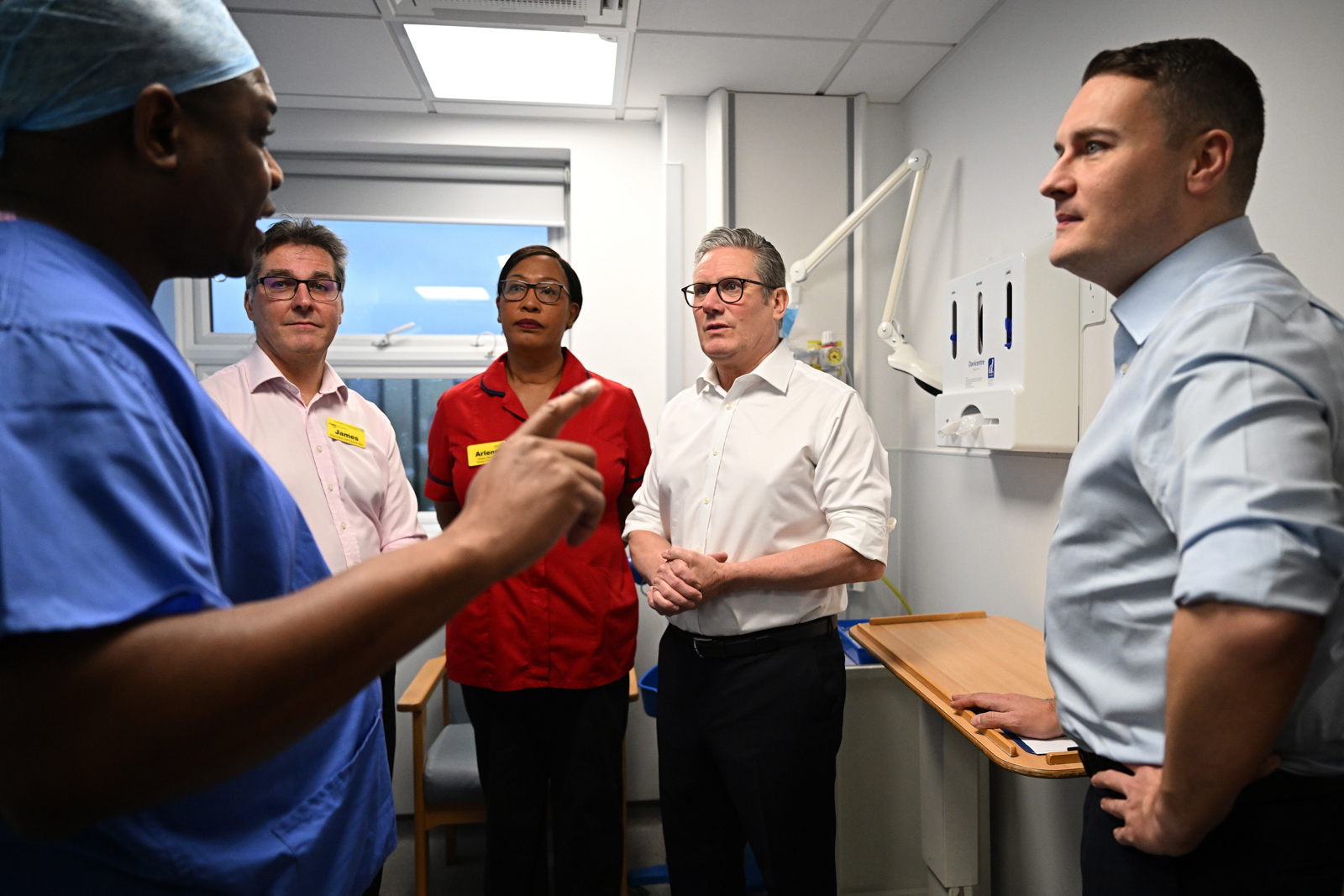

The health secretary accused the doctors’ union of ‘juvenile delinquency’. But he’ll need striking medics on side if he wants to fix the NHS

There are enough issues in the NHS to make any health secretary wince every time they walk into the office. In England, 7.4 million hospital tests and treatments are still waiting to be carried out. One in five patients are treated in hallways, offices and cupboards in A&E departments across the country and a staggering 16,600 people are estimated to die each year because a bed cannot be found in time.

It is a fragile, overstretched landscape, and one where both Wes Streeting and the government as a whole know they need to deliver tangible improvement. Yet even against that grim backdrop, Streeting has chosen to escalate a confrontation with junior doctors, now known as resident doctors, as they embark on their 14th strike in less than three years.

This week’s five-day walkout will take the total to 59 strike days. Operations and appointments are once again being cancelled and patients being told to avoid A&E unless it is an absolute emergency. For a service already operating at the edge of capacity, it is another blow — and, for the government, it is a politically dangerous one.

Resident doctors’ pay has risen almost 30% over the past three years, including 22.3% since Labour came into power. That fact has become central to the government’s argument that the British Medical Association (BMA) is making unreasonable demands. But the BMA, the doctors’ union, counters that inflation since 2008 has eroded doctors’ pay so significantly that an extra 26% increase over the coming years is needed simply to restore its real-terms value.

Pay, however, is only one part of the dispute. The other is jobs — or, rather, the lack of them. According to the BMA, this year more than 30,000 resident doctors applied for about 10,000 specialty training places — the jobs that enable them to progress to full-time specialist roles. This means a large number are out of full-time jobs, essentially stuck freelancing.

The government’s latest offer sought to address this by opening up more specialty training places but the union rejected it, arguing that it did not go far enough and contained nothing on pay. Streeting believes he is in the right. He argues that a further 26% pay demand is unaffordable, that public finances are in a perilous state and that the BMA is being unreasonable.

There are those who agree with him. In recent months, Streeting has proved himself to be a formidable communicator. When leaks from Downing Street suggested he was trying to overthrow the prime minister, his response won him significant praise from Labour MPs. He is quick on his feet, confident at the despatch box and increasingly comfortable framing opponents as out of touch with the public mood.

But winning the argument on breakfast radio is not the real battle here. Streeting is taking on a group of people he desperately needs on side if he is to deliver the lasting change to the NHS on which his own ambitions, and Labour’s electoral hopes, depend.

“He has never shied away from the fact he wants to eventually be prime minister,” one Labour MP told me. “So he needs to deliver on improving the NHS. That is what he will be judged on.”

It goes further than Streeting’s personal ambition to be remembered as the Labour health secretary who fixed the NHS. Across the parliamentary party, MPs speak with growing anxiety about the rise of Reform and the threat posed by Nigel Farage. Many believe that visible, sustained improvement in the NHS is one of the few areas where Labour can demonstrate competence, seriousness and an ability to govern.

“We simply cannot afford not to deliver here,” one senior backbencher told me. “People want their NHS improved and it might be one of the only ways we can prove we know how to govern.”

Labour has put in more money and more staff and productivity has inched upwards, but waiting lists barely budge. Those working inside the service talk constantly about shortages, bottlenecks and deepening demoralisation. It is against this backdrop that the government’s latest offer was rejected by 83% to 17%.

Ministers describe the package as generous: thousands more specialty training places, expanded opportunities, a long-term plan. Doctors see something else entirely — a jobs crisis in which “extra” places largely recycle existing roles rather than increasing real capacity, and where the fundamental problems remain untouched.

Overlay all of that with Streeting’s increasingly sharp rhetoric, accusing the BMA of irresponsibility, even “juvenile delinquency”. This may play well with sections of the public, although polling paints a mixed picture, with nearly 40% still backing the strikes. But within the health service, his words appear to have had the opposite effect, hardening attitudes and deepening resentment.

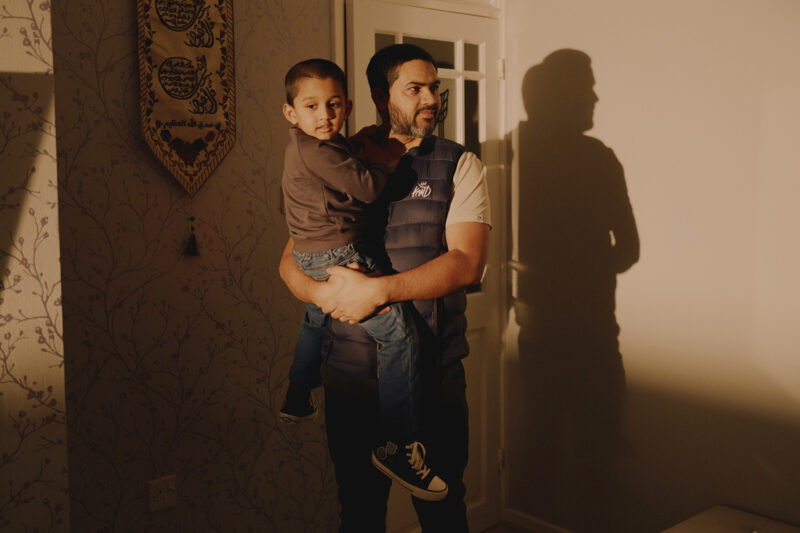

“This juvenile delinquent will be spending Christmas Day caring for patients in an overcrowded hospital,” one resident doctor told me.

The concern inside the government is that if Streeting normalises open warfare with doctors, he risks hollowing out the very coalition he needs to make reform stick. Productivity drives, service redesign, neighbourhood health centres and shifting care out of hospitals all require buy-in, particularly from resident doctors on the front line. You cannot reform the NHS in the way Streeting is looking to do against the will of the people who keep it running.

Streeting ended the last junior doctors’ dispute swiftly after becoming health secretary and he took credit for it. This time, the stakes are far higher. Picking this fight may win today’s headlines but it could cost him tomorrow’s legacy.

Shehab Khan is an award-winning presenter and political correspondent for ITV News.

Newsletter

Newsletter