Can the UK really define Islamophobia without using the word Islamophobia?

Experts weigh in on the UK’s attempt to codify a problem some call anti-Muslim racism or anti-Muslim hatred. Here’s what you need to know

What is Islamophobia? That question has vexed parliamentarians for the best part of a decade — and the government is finally said to be on the verge of adopting a formal definition.

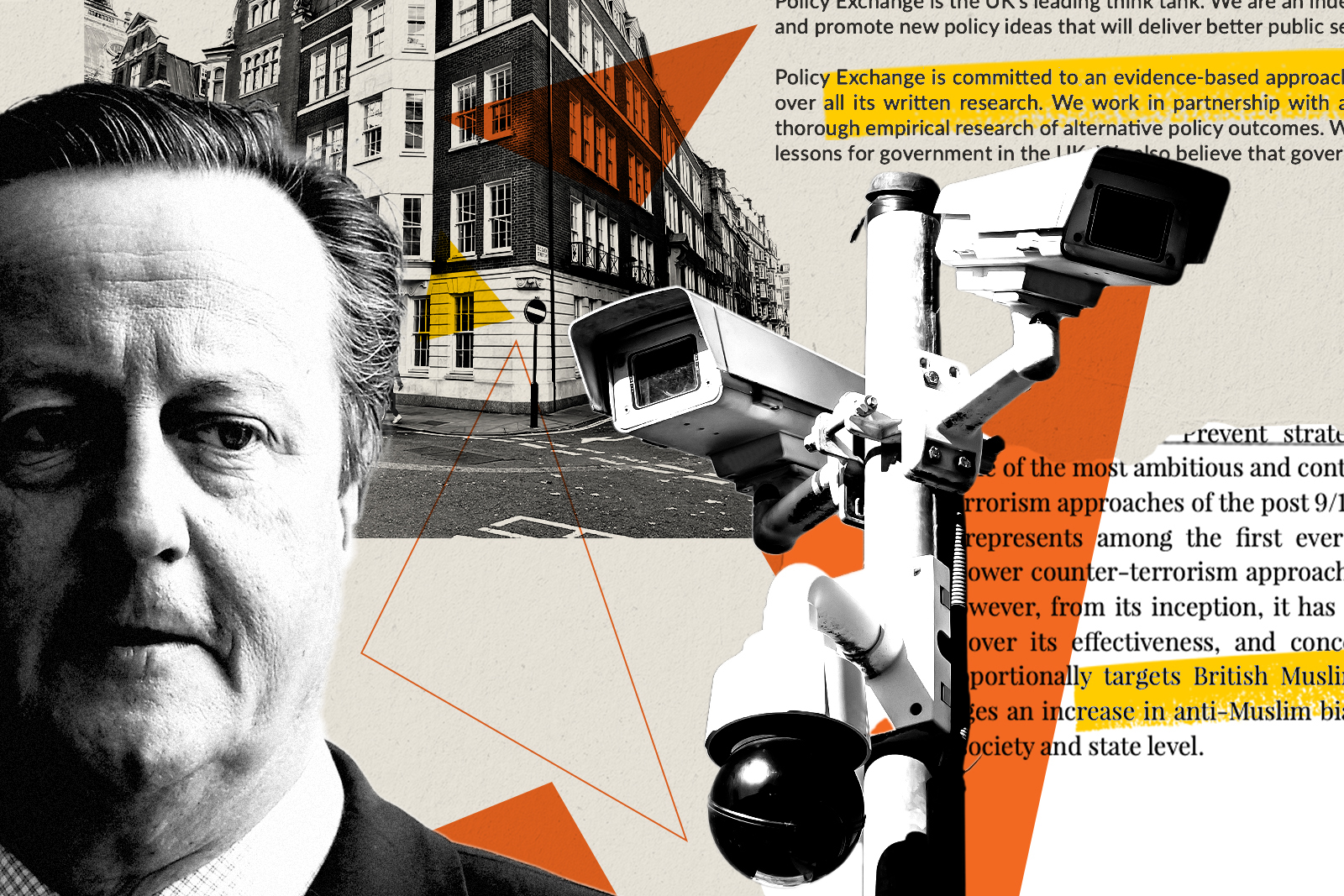

But the road to that definition has been tortuous. At least one form of words, proposed in 2019 by an all-party parliamentary group, has been scrapped. An influential rightwing thinktank has long opposed efforts to define it at all. And now the definition is expected to omit the word “Islamophobia” altogether.

Here’s what you need to know about the definition — what experts say about it, and what it means for UK Muslims.

Who came up with the definition?

In February 2025, the government announced it had tasked a working group, led by the former Conservative attorney general for England and Wales, Dominic Grieve, to come up with a definition of what it called “anti-Muslim hatred/Islamophobia”.

The group submitted its findings in October. At the time, Shaista Gohir — a crossbench peer as well as a member of the working group — urged the government to adopt the proposal in full or risk making Muslims feel like they “don’t matter”.

Calls for a formal definition had first gained traction as long ago as 2017, when the all-party parliamentary group (APPG) on British Muslims was established to address issues affecting Muslim communities, including coming up with a working definition of Islamophobia. The APPG subsequently defined Islamophobia as a form of racism “that targets expressions of Muslimness or perceived Muslimness”. Its definition was adopted by Labour, the Liberal Democrats, the Scottish National Party and the Scottish Conservatives. Wes Streeting, now the Labour health secretary, was part of the group.

But the definition was controversial. The rightwing thinktank Policy Exchange argued in a 2019 submission to parliament that it would undermine free speech. When Boris Johnson became prime minister later that year, he appointed Michael Gove, former chair of Policy Exchange, to oversee government work on the issue. Then, in January 2024, the Conservative government confirmed that it would not adopt a definition of Islamophobia at all, again citing concerns over free speech.

Labour was expected to take a different tack, having backed the APPG definition while in opposition. Instead, the party quietly backed away from the wording after winning the 2024 general election, and it was eventually shelved altogether.

Successive UK governments have struggled to agree on a formal definition of Islamophobia, having bowed to criticism that such a definition would amount to a blasphemy law. We spoke to experts researching the experiences of British Muslims about what they would like to see included and why the terminology itself matters.

Will the government use the term Islamophobia?

A report by the BBC earlier this week revealed the draft definition put forward by the government’s working group in October. Instead of Islamophobia, it used the term “anti-Muslim hostility”.

The group defined this as “engaging in or encouraging criminal acts, including acts of violence, vandalism of property, and harassment and intimidation whether physical, verbal, written or electronically communicated, which is directed at Muslims or those perceived to be Muslims because of their religion, ethnicity or appearance”.

It also spoke of “prejudicial stereotyping and racialisation of Muslims” and discrimination intended to disadvantaged Muslims.

Gohir told Hyphen that the group was still awaiting a formal response as to whether its advice would be accepted.

What have experts said about the APPG’s definition of Islamophobia?

Salman Al-Azami is a senior lecturer in language, media and communication at Liverpool Hope University. He still supports the abandoned APPG definition, of which he is a signatory. He says the group set out to ensure that the definition would not impede free speech.

“With the APPG definition, we wanted to take Islam out of it. People are free to criticise the religion, but it’s about the hatred people show towards people who appear to be Muslim.

“That’s why in the definition there is the element of ‘perceived Muslimness’. It’s about appearance and people’s perception. It’s got nothing to do with religion.”

Al-Azami believes Labour may be distancing itself from the term Islamophobia, which it previously adopted while in opposition, to appease critics from the political right.

Sunder Katwala, director of thinktank British Future, believes the term “Islamophobia” invites criticism from groups who have concerns about free speech purely because it contains the word “Islam”.

“Almost everybody coming up with a definition says it is not intended to cover critiques of Islam, but is intended to cover prejudice against Muslims. With the term ‘Islamophobia’, I think there’s a challenge in the way it signals Islam,” Katwala said.

“I think it blurs the boundary in making the distinction between the critique of ideas, and the prejudice against people.” He added: “It helps to tell people very clearly what they are still allowed to do, and that critique of theology and religion is free speech.”

What do experts want to see from the government’s definition?

Dr Amina Easat-Daas is a senior lecturer in politics at De Montfort University in Leicester with a special interest in how Islamophobia affects Muslim women.

“As a society, we understand racism and that it is a problematic thing,” she said. “We understand that it’s not just about the individual walking down the street who attacks a Muslim woman because of her headscarf. It does comprise that, but it’s fed by the political narrative, by policy and by legislation. These things work in a cycle.”

Of the government’s definition, she said it was imperative that prejudice against Muslims be recognised as a form of racism “so we recognise Islamophobia is systemic”.

Dr Mohammed Wajid Akhter, secretary general of the Muslim Council of Britain, said the organisation would like to see the government continue to use the term Islamophobia, describing it as a “common language” and “by far what is felt is the most appropriate term” in Muslim communities.

“For many across the community, the term Islamophobia is most commonly used in day-to-day language,” he said. “It is internationally recognised and captures the lived reality that we face on a daily basis.”

Is there a difference between Islamophobia and anti-Muslim hatred?

Majid Iqbal, chief executive of the charity Islamophobia Response Unit, believes the term Islamophobia is “all-encompassing”, and also captures hate, prejudice and hostility against Muslims.

He gave the example of a recent incident at the gym, where he overheard a group of men discussing the stabbing on a train in Cambridgeshire last month. “One person turned to another and said: ‘I hope it’s not one of those Muslims again,’” he said. “That’s Islamophobia, but I think it would be difficult to argue that is anti-Muslim hatred, because where is the hatred element?”

He also finds the terms “Islamophobia” and “Islamophobe” easier to use: “What’s the term for someone who displays anti-Muslim hatred? How would you describe them with one word? You can’t. Ease of use is very important.”

If the term “hatred” is used instead of Islamophobia, said Easat-Daas, “you don’t have to address the wider structures that are in place”. Pointing to scandals around the banning of headscarves for girls in schools, she said discriminatory policies and politics could be “hidden if we just talk about hatred between individuals”. If the government is opposed to the term Islamophobia, Easat-Daas suggested “anti-Muslim racism” would be more fitting than “anti-Muslim hatred”.

Similarly, Iqbal gave the example of MP Lee Anderson’s claim in 2024 that London’s mayor, Sadiq Khan, was “being controlled by Islamists”. Anderson, then a Tory MP, is now chief whip for Reform UK. “You might find it difficult to argue that as [being] hatred,” said Iqbal. “I think it would much easily fall into the bracket of being Islamophobic.”

What difference will a definition make?

The definition will be non-statutory, which means it will not be mandated by a specific law, and therefore will not be legally binding. However, its supporters say it will provide public bodies and employers with a better understanding of prejudice against Muslims.

Gohir, who also runs the Muslim Safety Net Service — a helpline that monitors hate against Muslims — said she believed people would be “far more likely” to report incidents “when their experiences are clearly reflected in an agreed definition”.

Despite the definition not being legislated, Gohir said it would “strengthen accountability and make it harder for legitimate concerns to be ignored or dismissed”.

Newsletter

Newsletter