Muslims often don’t trust palliative care. A new charity aims to change that

Al-Amal, founded by a doctor and a chaplain, is informed by the Muslim view of a good death — something they say is lacking in mainstream care

A new charity to support Muslims navigating palliative care is preparing to launch after Ramadan. As well as providing an emotional support telephone line, Al-Amal will also offer practical advice on accessing culturally and religiously appropriate care.

“We want to fill a gap which at the moment only seems to be widening,” said Nadia Khan, an NHS palliative care consultant who co-founded Al-Amal with Shakila Chowdhury, a Muslim chaplain from Birmingham. “The end-of-life journey can be immensely challenging for all patients and families, but for Muslims there are often additional barriers.”

The Muslim view of what a good death looks like is informed by values beyond the medical, Khan said. This can affect the way Muslim patients include their families in the decision-making process or their approach to pain management. But the ongoing lack of funding for hospices means that many are left unable to cater to patients’ spiritual and psychological needs.

“When cuts are being made, it’s often the psychological and spiritual care as well as community engagement work that is first to go,” she said.

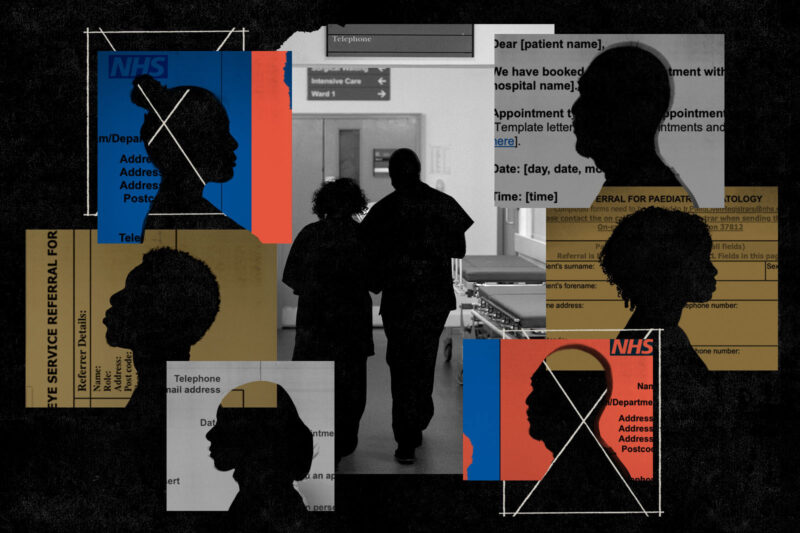

The marginalisation of patients from ethnic minorities in palliative care settings, however, predates the crisis.

“For the better part of a decade, we have seen report after report after report point to the same issues that ethnic minorities have in accessing palliative care: lack of trust, misconceptions around hospice care, worse satisfaction with care and worse outcomes,” Khan said. “We know what the problems are but we haven’t found a way to fix it.”

A 2024 survey carried out by King’s College London found that one in five people from ethnic minority groups had not heard of palliative care, compared to only 4% of white people. Additionally, nearly a third of people from ethnic minority groups did not trust healthcare professionals to provide high quality end-of-life care, and 18% believed that palliative care involved giving medicine to shorten the life of a patient.

Khan said that a belief that hospices provide medication to hasten death was a common misconception she encountered during her work, and one that can make patients reluctant to engage with services. She worries that Muslim communities may be particularly reluctant to engage with hospices where assisted suicide has taken place should the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) bill pass into law. The bill is currently undergoing scrutiny in the House of Lords and, should it pass, is not expected to come into force for four years.

“I think even a conversation about the topic might be very distressing to a Muslim family, but the healthcare professional might just see it as one of the options they are putting on the table. It might increase mistrust without healthcare professionals even realising.”

Additionally, many people believe that hospices do not provide outpatient care and that they will not be able to cater to religious and cultural needs.

“People are reluctant to speak about palliative care with people who don’t really understand their culture and faith,” said Erica Cook, associate professor in health psychology at the University of Bedfordshire, who has been working on a research project with Keech Hospice in Luton focusing on minority ethnic communities. “For example, we found that the phrase ‘end of life’ didn’t really resonate with Muslims, who thought of death as a transition, part of a journey, not the end.”

The communication barriers and distrust communities feel towards hospices leads to the resources being underused by patients from minority groups.

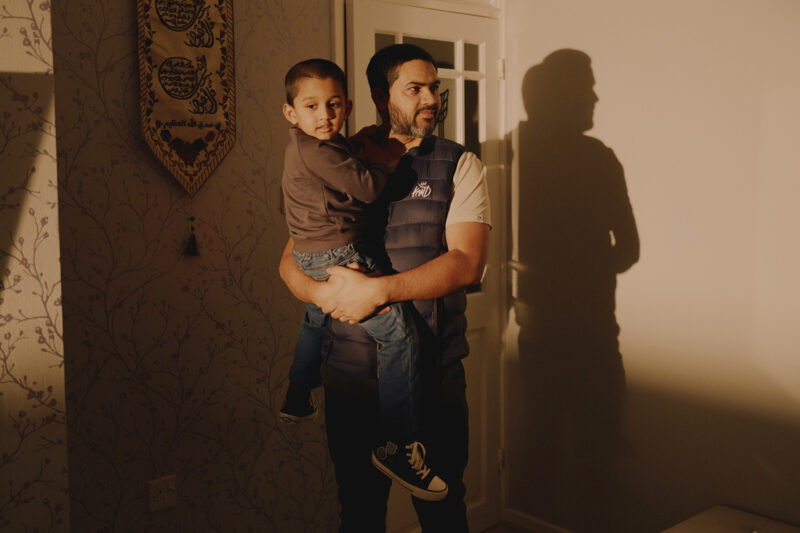

“Luton is one of the three places outside of London where the majority of the population comes from minority ethnic backgrounds, but the hospice patients did not reflect that. When we spoke with community members, we found that many were reluctant to engage with the hospice because they did not want their loved one to be institutionalised. They did not want them to be taken from their homes where they are loved and cared for,” she said.

Cook added that many older patients were scared of interacting with hospices due to past experiences of discrimination in hospitals, while carers felt that the hospice services did not cater to their family’s needs.

One carer participating in the study said that home visits from hospice workers felt like an “alien invasion”.

“Carers don’t want to be replaced by healthcare workers — they want to be better supported so they can meet their loved ones’ needs,” Cook said.

Newsletter

Newsletter