What the Bradford school strike can teach us, 40 years on

In 1985, with far-right rhetoric on the rise, Muslim parents pulled their children from classrooms in protest against a controversial headteacher

Along with students across the country, pupils at Iqra academy in Bradford have recently embarked upon a new academic year. The school boasts a newly built, wood-panelled annex, but on the sandstone facade of the original Victorian building its original name — Drummond Road board school — is carved in imposing block capitals.

In the surrounding Manningham district, nearly 80% of residents come from South Asian backgrounds and a similar percentage are Muslim. Just around the corner sits a halal butcher and a small mosque; a little further away is the Bismilla Banqueting Hall, one of many local venues that cater to large Muslim weddings.

This year, Bradford is enjoying its status as UK City of Culture, with venues large and small celebrating the diversity and creativity of the local area. Forty years ago, though, the story was radically different and Drummond middle school, as it was then known, was at the centre of a nationwide scandal about immigration, multiculturalism and racism in the British education system.

Parents across the city withdrew their children from classes, a media frenzy broke out and heated debates played out in parliament. Margaret Thatcher, then prime minister, also got involved. For all the headlines it generated, the 1985 school strike has been largely forgotten today. Yet it is a moment worth revisiting, filled with striking parallels to contemporary issues of Islamophobia, the threat of rising far-right discourse and anxieties around so-called woke culture.

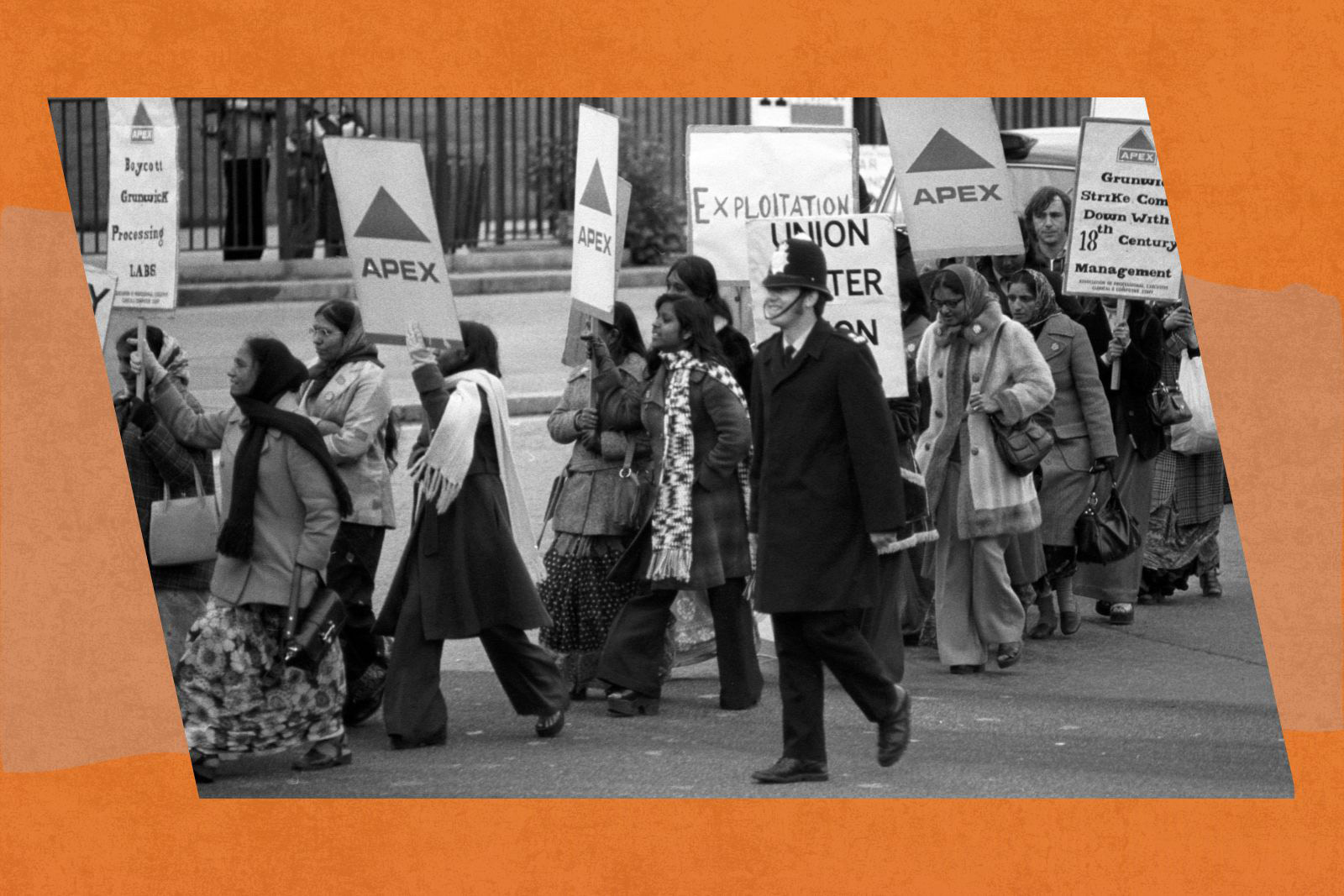

In many ways, Drummond was a typical 1980s inner-city state school. One thing that did distinguish it, however, was that around 95% of its student body had ties to former British colonies in the Indian subcontinent. Most of their parents came from rural Pakistan and had moved to west Yorkshire in the 1950s and 60s to work in the region’s textile industry.

A couple of decades later, most of the mills had closed, unable to keep pace with international competition, and unemployment in Bradford had risen to rates not seen since the 1930s. The far right fed off that poverty and built an outsized influence in the city. Groups such as the National Front, which advocated for the enforced repatriation of foreign-born people to their countries of origin, staged a number of violent demonstrations in Manningham and other ethnically diverse areas.

Against that backdrop of fear and discrimination, in 1981 Drummond appointed a new headteacher. Named Ray Honeyford and born to a working-class Manchester family in 1934, he had left school at 15, but retrained to become a teacher later in life. Having steadily worked his way up the ranks, the job at Drummond was his first running a school.

By the time Honeyford arrived at Drummond, schools had become political battlegrounds. National Front literature belonging to teachers had been found in institutions across Bradford, along with racist stickers and graffiti. The abuse directed at local South Asian children was so severe that some were too scared to attend class. One retired teacher openly campaigned in favour of racial segregation within the education system.

Honeyford’s hiring coincided with the decision of Bradford council to remedy the situation. A new set of policies were introduced, designed to celebrate diversity rather than stigmatise it. Multiculturalism became the new watchword.

Council leaders declared that parents had the right to information about their children’s schooling in Urdu and Punjabi, the languages spoken by many local residents. Muslim pupils could take part in Friday prayer sessions at school and any institution with more than 10 Muslim pupils was obliged to serve halal meat at lunch.

For Honeyford, a staunch integrationist, such measures were unacceptable. In the months that followed, he took it upon himself to become the figurehead of resistance, authoring a series of articles in the Times Educational Supplement in 1982 and 1983 that took aim at the city council’s reforms, accused politicians of confusing education with propaganda and — somehow — compared the new emphasis on inclusivity to the anti-communist witch-hunts led by US senator Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s.

Honeyford’s most controversial article, published in January 1984 in a hardline conservative magazine titled the Salisbury Review, was nakedly prejudiced. He suggested the people supporting multicultural education had the “hysterical political temperament of the Indian subcontinent” and that the reforms would introduce what he described as a “purdah mentality” in schools.

Honeyford found it ironic that the parents of the children under his tutelage at Drummond enjoyed rights and privileges that were “unheard of” in places such as Pakistan, a country Honeyford dismissed as being full of “backward people”.

In March 1984, Urdu translations of those writings were distributed to the terraced houses that surrounded Drummond. Before long, a campaign was launched to remove Honeyford from his position.

The rationale of the campaign against Honeyford was laid out in the Times by a local Muslim parent, who worried about the detrimental effect that Honeyford’s views might have on students’ self-esteem. “We send our children to school for a decent education, but if Honeyford is a racist, what will the children be like?” they asked.

Honeyford had not only insulted the parents of the children under his care, protesters argued. He was also openly flouting the council’s new ethos of respect for cultural difference. In spring 1984, a petition with 500 signatures was presented to the council, calling for his removal. Soon, hundreds of parents requested that their children be transferred from Drummond to other schools.

Events in Bradford began to attract national attention. In 1984, in his regular column in the Times, the rightwing philosopher and editor of the Salisbury Review Roger Scruton used the furore at Drummond to expand his theory that anti-racists in Britain had become a “totalitarian elite” who were trying to silence critics of the multicultural agenda.

Marcus Fox, a Conservative backbench MP for the affluent — and mostly white — town of Shipley, four miles north of Bradford, dismissed those campaigning against Honeyford as a “rent-a-mob” conducting a smear campaign.

“If Mr Honeyford is ultimately dismissed, where will it all stop?” Fox wondered in a House of Commons debate. “The race relations bullies may have got their way so far, but the silent majority of decent people have had enough.”

Although Thatcher did not comment directly, she made it clear where her sympathies were. At the height of the scandal, she invited Honeyford to a special seminar at 10 Downing Street to discuss the future of education in Britain.

The campaigners against Honeyford were, however, not deterred. On 4 March 1985, the parents withdrew 250 of their children from Drummond and sent them instead to a week-long alternative school that had been established at a local Pakistani community centre. By the new academic year in September, picket lines were in place at Drummond each morning. Parents and children lined the school gates next to slogans like “Ray-cist” and “Honeyford writes in the blood of blacks”.

Then, on 15 October, the parents of 4,000 Muslim schoolchildren across Bradford withdrew their sons and daughters from school in protest. Those still attending were given a leaflet reminding them that Honeyford had insulted their culture and urging them not to be intimidated.

Eventually, the pressure being applied by local protestors brought the situation to breaking point. In December 1985, after a full term of chaos, during which Honeyford was the subject of intense discussion in supermarkets, pubs, mosques and tea houses, it was announced that he would be taking early retirement.

His payoff of £160,000 — the equivalent to £500,000 today — was believed to have been the most generous ever received by any UK teacher.

Looking back, the Honeyford affair was never solely about the ability of a teacher with reactionary views to lead a school like Drummond. While Honeyford may not, as some claimed, have had a “silent majority” on his side, he certainly had his supporters.

“Why shouldn’t a man say what he thinks?” one local asked a visiting journalist at the height of the controversy. “This used to be a free country till all them buggers arrived — now people are afraid to speak their mind.”

For some in Bradford and elsewhere, Honeyford was a symbol for a broader set of anxieties around immigration and the whole multicultural project. Today, it is increasingly clear that those concerns never went away. In fact, the feelings Honeyford tapped into appear to have only entrenched themselves more deeply in our political culture.

In the early 2000s rightwing newspapers such as the Daily Mail and the Sun repeatedly referred to “political correctness gone mad”. This now-hackneyed phrase was often used to describe manufactured scandals such as local councils and schools allegedly renaming Christmas celebrations “Winterval” and the removal of Bibles from hospitals, in order to avoid offending Muslims and other non-Christians.

In 2013, a year after Honeyford’s death at the age of 77, another furore erupted over false claims that fundamentalist Muslims had attempted to take over the running of a Birmingham school. It would eventually become known as the Trojan Horse scandal. In the fallout that followed, Scruton summoned Honeyford’s ghost, arguing that his earlier warnings about multiculturalism had been correct and questioning whether the primary loyalty of Muslims could ever be to a British identity.

Honeyford has even crept into the ongoing schisms over Brexit and arguments made by Reform UK leader, Nigel Farage, that immigration to Britain is out of control. In response to a social media post by Farage that “Government policy has totally failed to integrate people into our society”, one user responded: “Didn’t poor Ray Honeyford warn about this in 1985? Was dismissed as a racist and lost his job – the creed of multiculturalism needs to end.”

Now, few people refer to political correctness, gone mad or otherwise. Instead, a new set of buzzwords are used to advance the same old talking points, “woke” culture and the “diversity, equality and inclusion agenda” among them. While the basic arguments are almost identical, the debates have arguably become even more heated than they were in Honeyford’s time, with social media fuelling an intensified polarisation.

The central lesson that the Honeyford affair has to teach us now is the importance of dialogue across ideological and cultural divides. While the policies introduced by Bradford council sought to counter the very real threat of rising racism, the main problem they faced stemmed from the initial messaging.

The idea was allowed to take root that multiculturalism meant a set of gains — material and otherwise — that would solely benefit non-white immigrants and their families. Figures such as Honeyford and Scruton encouraged people to see the entire enterprise as a zero-sum game: if Bradford’s Pakistani Muslim community was gaining, then the city’s white population had to be losing.

That perspective completely ignored a much bigger story about the changes that were taking place in British society. The immigrants who made their homes in Bradford in the 1950s and 60s were only the latest chapter in a long and ongoing story of migration to the city. When they arrived, South Asian families were attempting to build lives alongside people whose parents or grandparents had moved to the UK from Ireland, Germany, eastern Europe and beyond.

A more inclusive vision of multiculturalism might have emphasised that diversity and noted it as an increasingly important part of British life. It could also have emphasised the shared histories and values of different generations of immigrants and recognised the structural issues of poverty and lack of opportunity that continue to blight the lives of people across the country.

The economic hardships being experienced in Bradford at the time of Honeyford’s appointment at Drummond affected working-class residents from all backgrounds, regardless of when they arrived. By the end of the 1980s, an estimated 50,000 jobs had been lost in the city. None of that had anything to do with the provision of halal meat in local schools, just as the temporary housing of asylum seekers in hotels today has nothing to do with a sluggish economy and decades of under-investment in public services.

The last time I was in Bradford, the city was in the middle of its literature festival. It was a summer Saturday afternoon and the sun was shining. As I walked through the town centre, an elderly Black man was blasting Bob Marley from a boombox and union flag bunting was being strung up in preparation for the city’s armed forces day celebrations. A bit further along was an advertising hoarding with the slogan “Nothing beats nanny’s naan”.

The events of 40 years earlier couldn’t have seemed further away, but you don’t have to spend long looking at the news to see that they are now more relevant than ever.

Kieran Connell is a writer and historian at Queen’s University Belfast. His most recent book is Multicultural Britain: A People’s History.

Newsletter

Newsletter