‘A man constructing his own line in life’: on the legacy of Hamad Butt

Butt’s contemporaries remember his influence as a Young British Artist, and call for his work to be recognised as part of a larger canon

In August 1995, at a Tate Gallery group show titled Rites of Passage: Art for the End of the Century, an iodine leak caused by a crack in one of the glass rungs of an installation by British Pakistani artist Hamad Butt resulted in the museum being evacuated. “Contemporary art is fast becoming a health hazard,” wrote David Lister, a critic at the Independent.

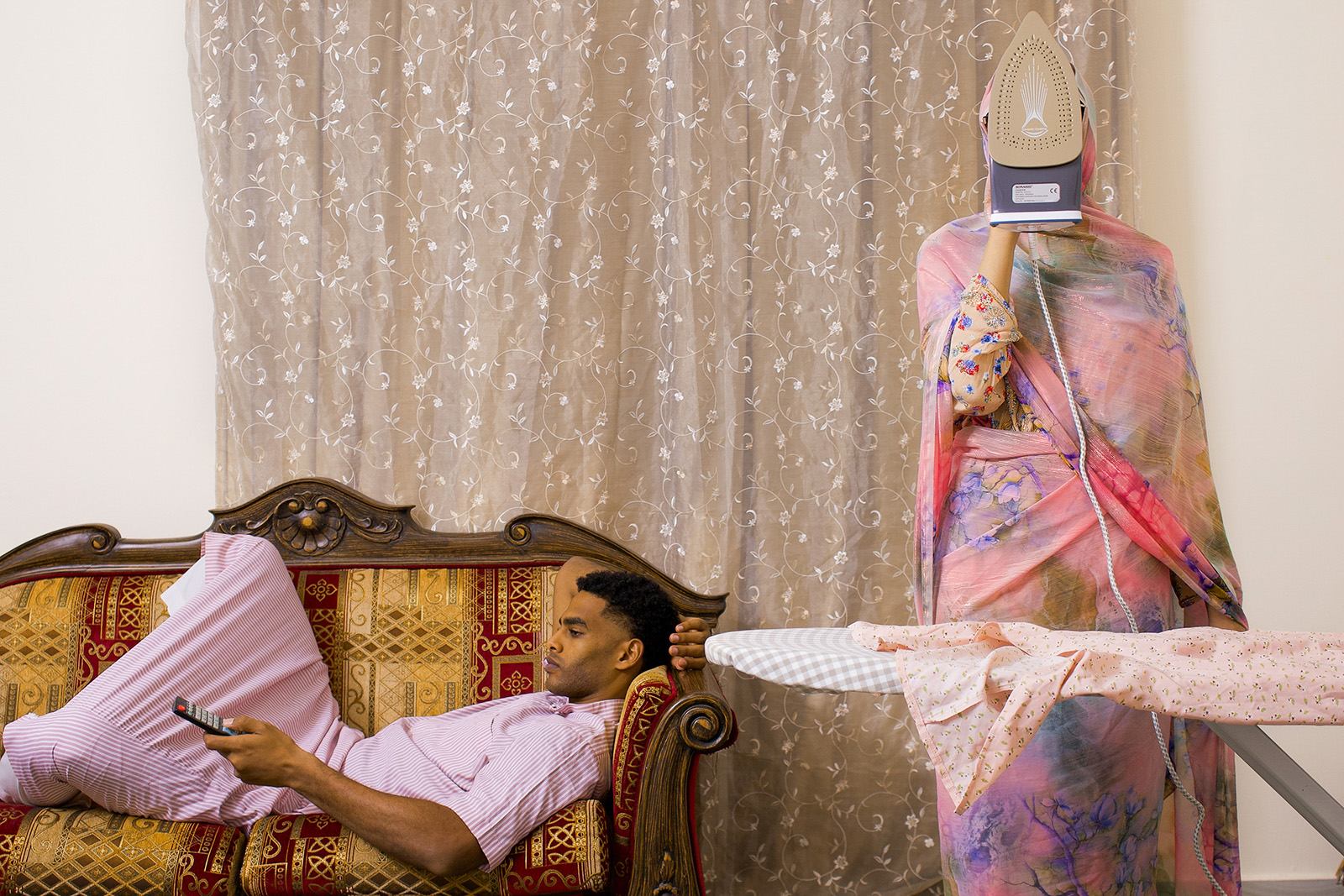

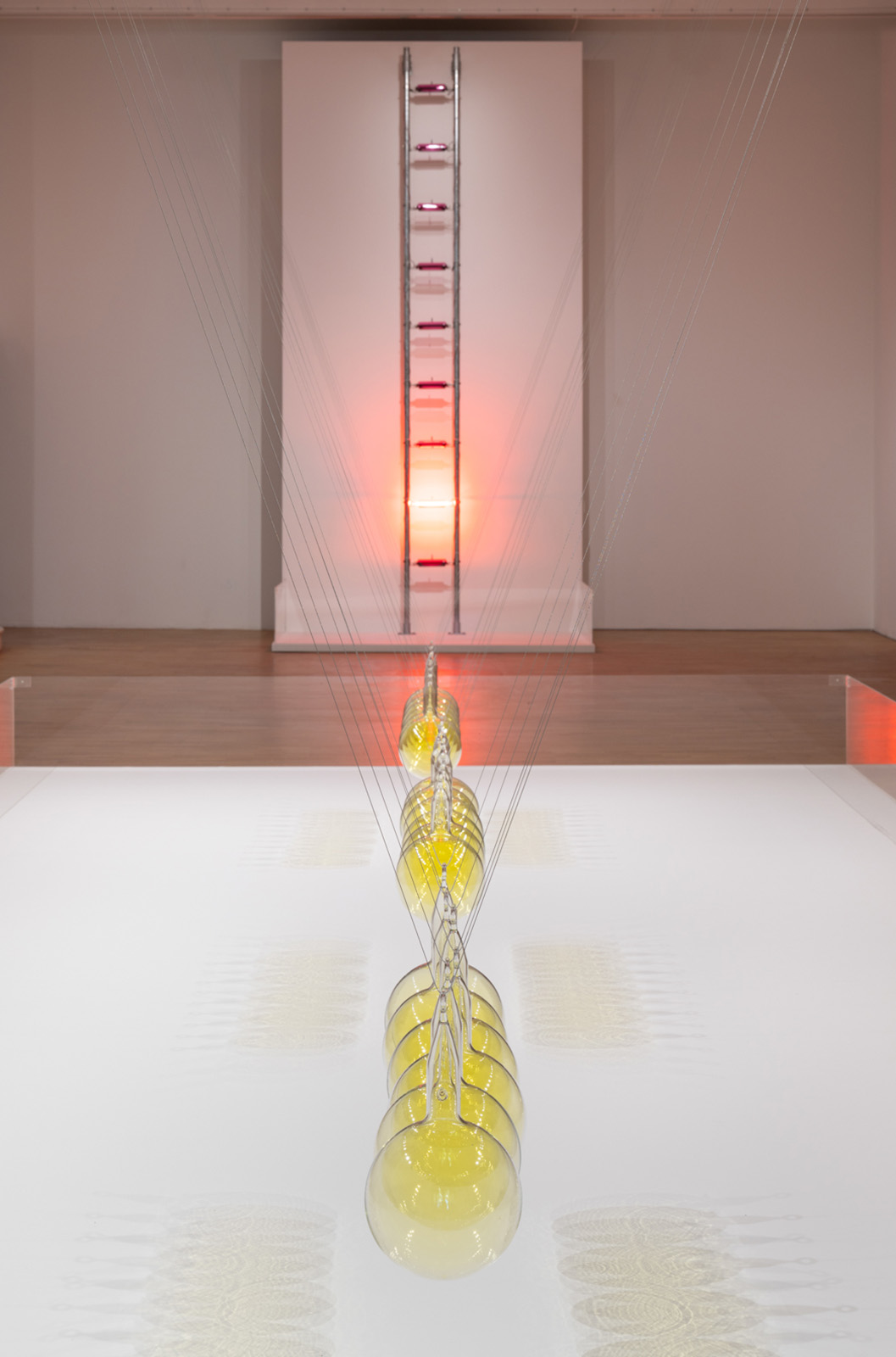

Thirty years later, Familiars (1992), Butt’s final work, greets visitors at London’s Whitechapel Gallery. Hamad Butt: Apprehensions is the first comprehensive survey of the artist’s oeuvre since his death from an Aids-related illness in 1994.

Comprising three sculptural elements, each incorporating the halogens iodine, chlorine and bromine in their primary states, Familiars was conceived in the aftermath of Butt’s HIV diagnosis and gestures at the central concerns of his practice: the simultaneous notions of contagion, fear, desire, attraction.

A multihyphenate long before the term gained currency, Butt worked across artistic mediums and innovated within them. At Goldsmiths, University of London between 1987 and 1990, he was a contemporary of the group that would later become mythologised as the Young British Artists (YBAs), but his death at 32 cut short a career that was in its early stages of germination.

Born in Lahore, Pakistan, in 1962 and raised in east London, Butt came of age at a time of virulent racism espoused by groups such as the National Front. His younger brother Jamal recalls being chased home after school and beaten up on various occasions. “From a cultural perspective it was tough,” he says. “But the family home was very close-knit and happy.”

Though he did not identify as Muslim later in life, elements of Butt’s religious upbringing appear throughout his art. “He was a spiritual person who was on a constant search for truth,” says Jamal. “He was constantly trying to marry up his sexuality with his religious and cultural background.”

In an essay for the exhibition catalogue, art historian Alice Correia has likened the placement of a series of glass books in Transmission to a Qu’ranic study circle. Elsewhere, Islamic architectural forms such as arches are evoked.

Art historian Dominic Johnson, the curator of Apprehensions, describes Butt’s work as an important precedent in the conversations between art and science, as well as in “the way he explores emotions, the way he evokes them in the space, his use of the iconographic mode to talk about sex and sexuality, his explorations of religion and heritage”.

Some of Butt’s paintings, which on display for the first time, show an aesthetic approach present in the works of artists who have interrogated questions of sexuality, masculinity and intimacy in the decades after Butt’s death. In one painting, a nude male figure bathes in a hammam; in another, muzzled dogs chase two nude male figures.

“What would an artist like Salman Toor or Prem Sahib have done if they’d been introduced to Hamad Butt at art school or early in their career?” Johnson asks.

Rendered invisible in the public archive, Butt pioneered a way of articulating queerness that was not known to his contemporary successors. “His legacy is still in flux, because it was silent for a long time,” Johnson says. “People are shocked and embarrassed — how is it possible not to know this amazing work? As though it’s a personal failing on their part. It’s actually an institutional failing.”

Also included in the retrospective is a recreation of Fly-Piece, a component of Butt’s thesis project in 1990. It is a glass-panelled case in which a colony of bluebottle flies feed on sugared paper. They lay eggs, give birth, and die, capturing a complete life cycle.

Damien Hirst, a contemporary of Butt’s at Goldsmiths, would go on to use flies in his own work a month after Butt presented the work. The appropriation left Butt distraught. “He was perplexed and very upset,” recalls the artist and lecturer Diego Ferrari, who was a friend and classmate of Butt’s.

Fly-Piece, one of the earliest examples of what would later become recognised as bioart, was destroyed by Butt in the aftermath of the Hirst affair. “It needed to be returned to the conversation, to be part of his practice,” says Johnson, on recreating the work for the Whitechapel Gallery.

Jamal has long fought for Butt to be recognised as part of a larger canon. It took 20 years for the Tate to acquire Familiars as part of its permanent collection, following a campaign by Jamal and a petition signed by prominent creatives including Isaac Julien, Steve McQueen and Angela Bulloch.

“I would like the legacy of the show to be that you can’t get away with having a book on queer art in the UK, or British South Asian art, or diasporic British art, or art and science, without Hamad being included,” says Johnson.

As visitors exit the main exhibition spaces of Apprehensions and enter a room devoted to ephemera from Butt’s archive, a film plays on a loop. It is a home video that Jamal shot six months before Butt’s death. Butt had returned to the family home in Ilford, east London, increasingly ill.

“I thought there may come a time when people would want to hear, in his own words, what the work meant,” Jamal says of his motivation to make the film.

“What do you think your art does?” Jamal asks his brother. Butt tells him that he is the wrong person to ask, that once the art is in the public realm, its meaning is constructed by those who view it.

What, then, does Butt’s work mean in our present moment? “We are still in an era of transmission and fear,” Ferrari says, referring to the fact that, even after a treatment for HIV has become available, stigma surrounding the disease and sexuality remain. And, in a time of renewed xenophobia and division, his art is hauntingly resonant.

In his only published interview, with the magazine Square Peg in 1985, Butt voiced his aversion to labels: “Some people choose to identify themselves more strongly with their Asian, or whatever, cultural backgrounds. I won’t deny it to myself but I won’t speak for it. In the same way I don’t primarily regard myself as a gay artist.”

Ferrari recalls an anecdote that captures this element of Butt’s fluid nature: his refusal to ascribe an identity or neat meaning to himself and his art. One afternoon at Goldsmiths, he and Butt went to a cafe. On one side, Hirst and some of the YBA crowd was seated, and on the opposite end a few other students from the same year.

The two groups were in the middle of a conversation. Hirst gestured to Butt and Ferrari, waving them over to his side. Butt declined the invitation, choosing to sit in the middle, belonging to neither group.

“That shows you the kind of psychological space he inhabited. He wasn’t a man of extremes. He was a man constructing his own line in life,” Ferrari says. “Not to be on the right or the left of the line, but to be the line itself.”

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions is showing at the Whitechapel Gallery until 7 September.

Newsletter

Newsletter