Sholay at 50

Ramesh Sippy’s seminal masala western is one of the most popular films of all time. Here, its writer and some of the movie’s biggest fans discuss its appeal

By any measure, 1975 was a banner year for film-making. Its most popular movies offered something for everyone — water-borne terror (Jaws), literary cachet (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest), hit songs (The Rocky Horror Picture Show and Tommy) and, inevitably, a franchise sequel (The Return of the Pink Panther).

Fifty years after its release, one film from India also holds a special place in the hearts and minds of tens of millions of South Asians worldwide.

Sholay, directed by Ramesh Sippy and released on 15 August, 1975, is one of the most successful films of all time — an action-packed “masala western” which broke all box office records for Indian cinema for nearly two decades and now regularly tops fans’ and critics’ polls worldwide.

The film, which earned nearly $17m in 1975 (more than $100m in today’s money), has also been lavishly garlanded by cineastes for decades. The BBC described Sholay as “the Star Wars of Bollywood” in 2015. In 2002, it was voted No 1 in the British Film Institute’s top 10 Indian films of all time and in 2005 the Indian magazine Filmfare named it the best film of the past 50 years.

In 2005 the Indian magazine Filmfare named Sholay the best film of the past 50 years

Sholay’s success has few comparisons. While millions have watched Indian movies such as Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (The Brave-hearted Will Take the Bride, starring Shah Rukh Khan) and Mr India (Anil Kapoor) on video, DVD and streaming platforms, no other Indian film has had such influence over South Asian cinema.

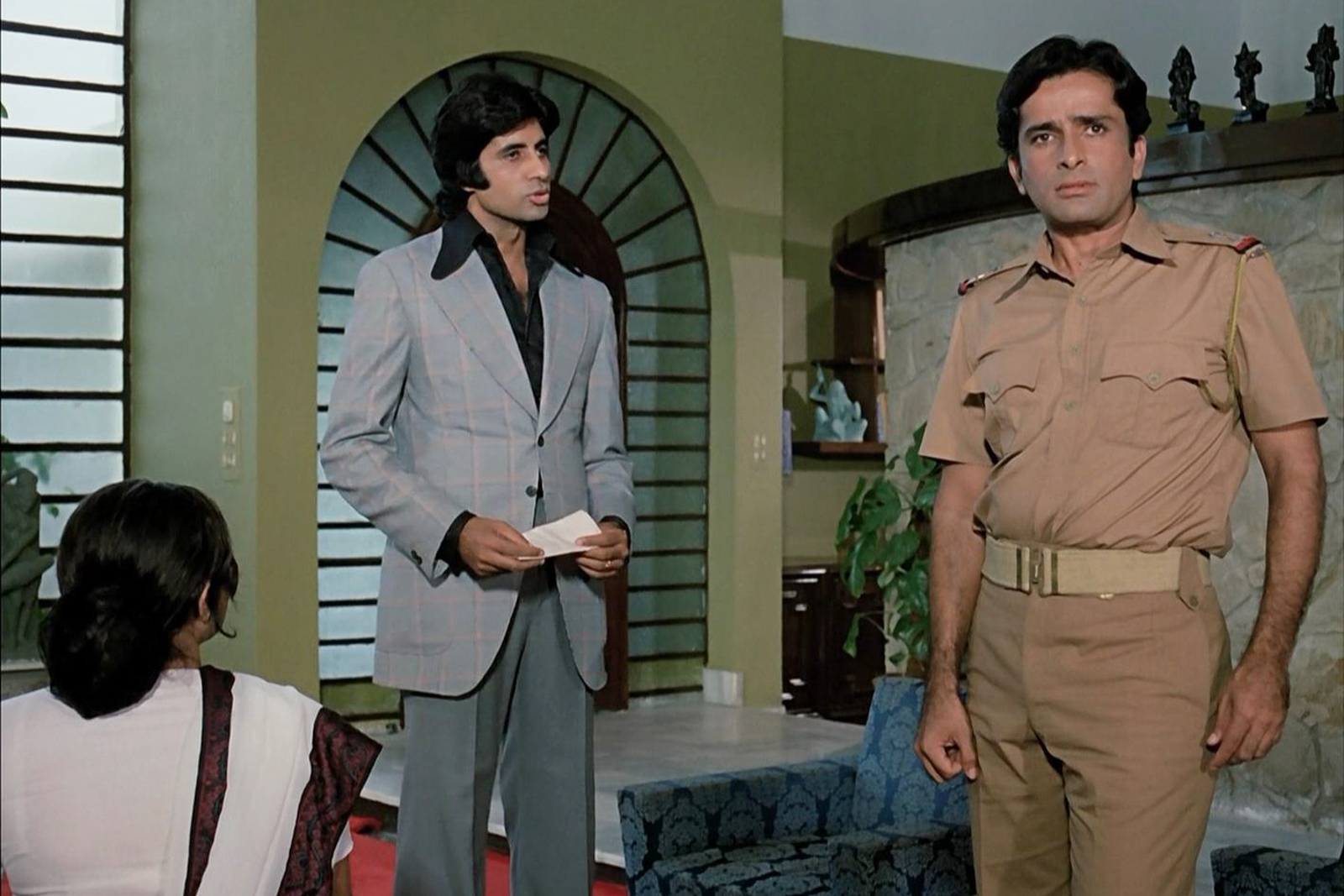

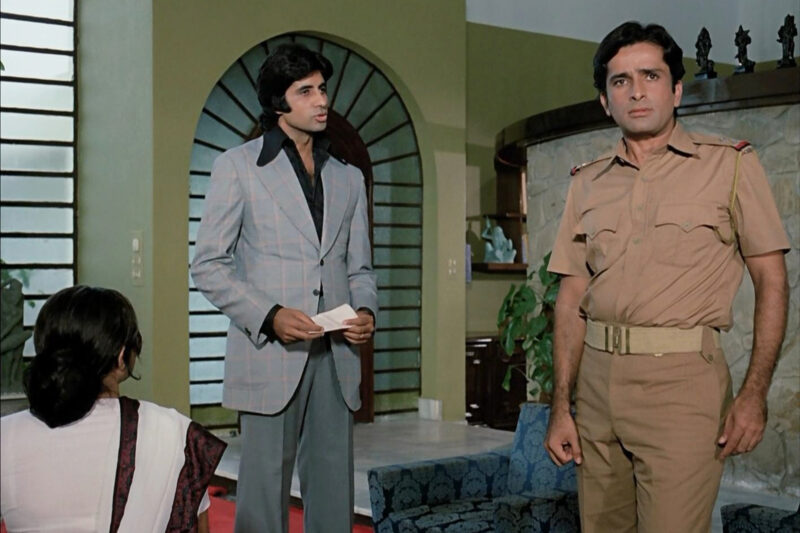

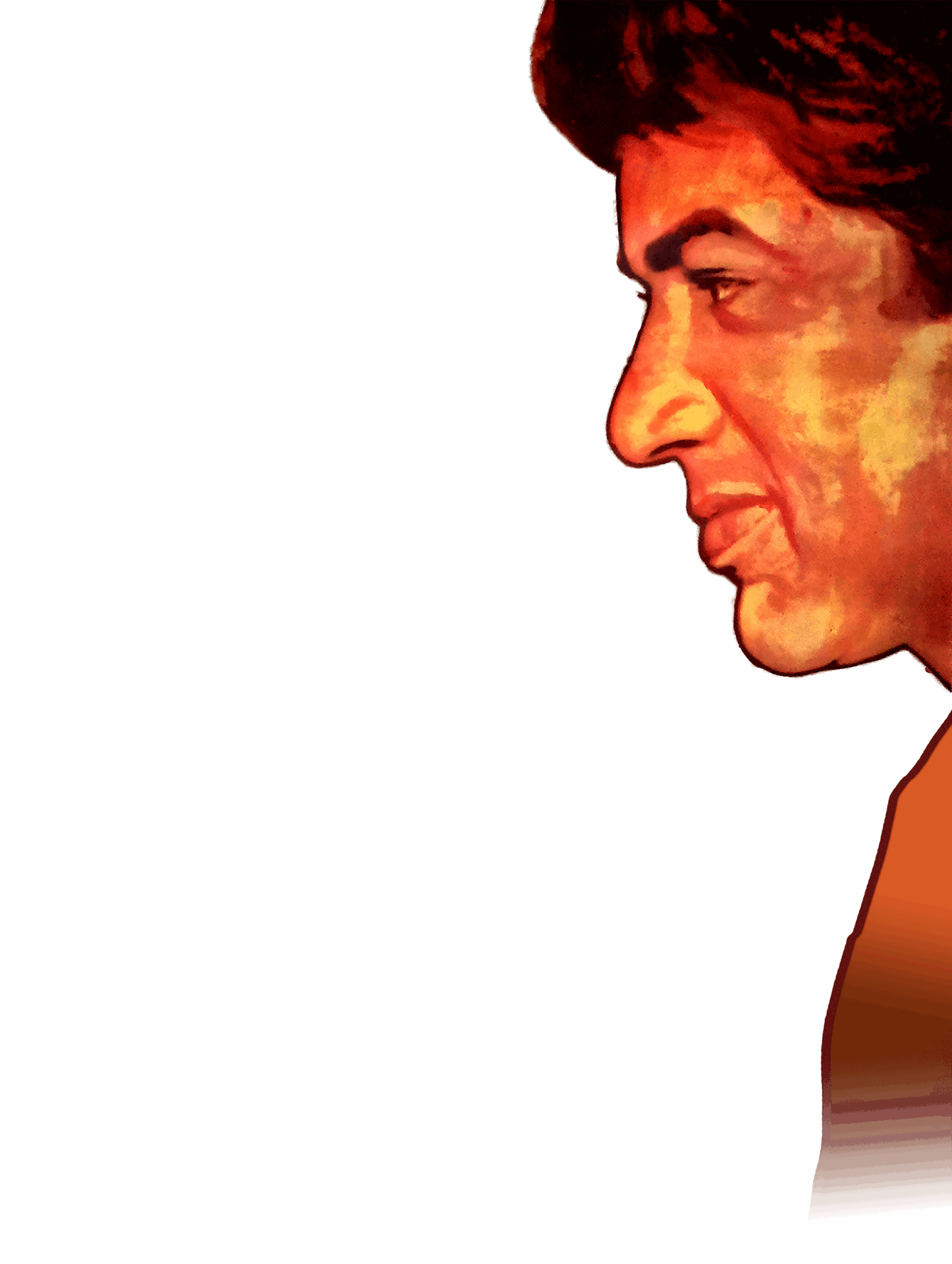

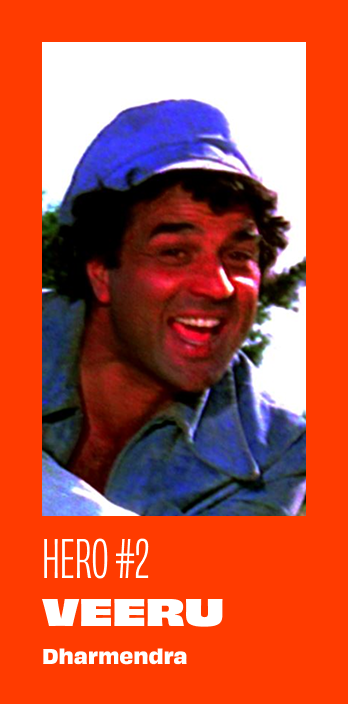

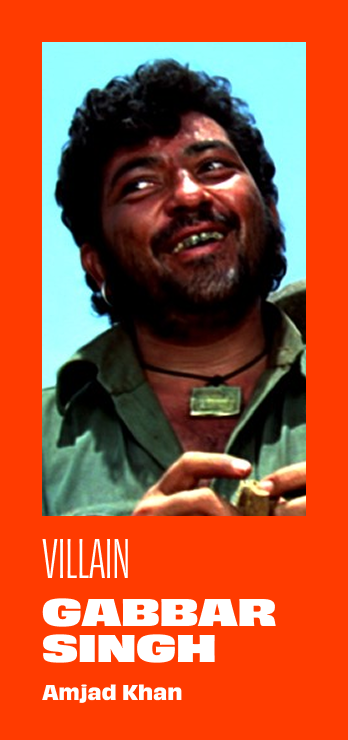

The storyline — loosely inspired by John Sturges’ 1960 western The Magnificent Seven and Akira Kurosawa’s seminal Seven Samurai (1954) — is a simple retelling of ordinary people rising up against injustice. After a murderous bandit and his gang of thieves repeatedly pillage the fictional village of Ramgarh, residents desperately look for outside help. Former police chief Thakur (Sanjeev Kumar) hires two petty thieves, Jai (Amitabh Bachchan) and Veeru (Dharmendra), to capture the villain Gabbar Singh (Amjad Khan) and restore peace.

As the first Indian movie to be shot in 70mm widescreen, Sholay revolutionised the country’s film industry and made superstars out of its cast. Its audacious action sequences include a thrilling train hijacking, numerous horseback chases and a series of fighting and musical sequences.

In a 2020 speech in the Indian city of Ahmedabad, President Donald Trump received a roar of approval after name-dropping the film while praising the country’s arts. “All over the planet, people take great joy in scenes of bhangra, music, dance, romance and drama… and classic Indian films like DDLJ and Sholay,” he said.

The post-release reaction to Sholay was not initially favourable, though. One critic rated the movie “average”, adding that it had everything except “high intelligence, art and purpose”. Audiences, however, were spellbound. In contrast to today, when Hollywood films can disappear from big screens after a couple of weeks, Sholay played in one Mumbai cinema for five years.

Penned by Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar, Sholay cemented one of Indian cinema’s most durable and successful screenwriting partnerships. Over the next few years, the duo wrote a string of box-office hits, including Don (1978), Kaala Patthar (1979) and Shaan (1980) — many of them starring Bachchan.

‘I feel Sholay is perhaps

the last folklore India has made’

Javed Akhtar, screenwriter

“Whatever Sholay has become, it has become because of the audience, who have contributed. I feel Sholay is perhaps the last folklore India has made,” said screenwriter Akhtar on the film’s enduring appeal.

“Sholay was a very fine combination of tempo, speed and depth,” he added. “And it worked. It opened people’s eyes that, yes, it is possible to make a big-budget film and it can come back with profit. The making of Sholay was an era. It had its own culture and civilisation, it was like a complete industry to itself.”

Generations of British-Asians in the UK have experienced the rite of passage of watching Sholay with their parents and siblings, on VHS tapes in the 1980s, later on DVD, then via streaming services.

Nusrat Ghani, Conservative MP for Sussex Weald, said: “We used to hire movies from a movie store for a weekend. It was much more of a communal moment — not like now, where you can scroll back and forth on your phone. We had to watch it on a VHS tape, a chunky thing that you put in a VHS recorder. You’d watch it a couple of times before you took it back.

“I remember watching Sholay on my parents’ sofa in the Midlands. You did all your prep in the morning before you sat down: you always got the pakoras and the samosas ready. Somebody else was on tea duty because I wasn’t going to get up in the middle of the movie.”

Younger viewers remember watching the film on DVD. BBC Asian Network presenter Haroon Rashid recalls: “The first time I went to Pakistan was in 2002. DVDs by that point had become common and they were very cheap. My dad made an effort to come back with as many DVDs as possible, and Sholay was one of the ones that was top of the list. He wanted to share a piece of his childhood with me and my sister.”

Sholay’s breakout star was Khan, who played the wily Gabbar Singh, a notorious bandit who had evaded the police and whose presence — even among his own gang of followers — inspires fear.

Khan, in his first major role, seemed to delight in the scene-chewing villainy his role offered, on a par with Anthony Hopkins’s terrifying Hannibal Lecter or Alan Rickman’s steely Hans Gruber. Wicked laugh? Check. A murderous sociopath who wipes out entire families, including women and children? Check. Fifty years after Sholay’s release, Khan’s performance lives on in social media in the form of gifs, viral social media videos and AI-generated content.

For generations of youngsters who grew up watching Sholay, the threat of a visit by Gabbar Singh was a common and sobering experience. Parents would admonish their children to stop fighting, or “Gabbar ajaye ga” (Gabbar will come).

But Sippy’s film is also a subtle protest against the authoritarian politics of the day in India. At the time, the government of Indira Gandhi had declared a state of national emergency, launching an unprecedented crackdown on ordinary Indians, including students and critics, while postponing parliamentary and state elections.

Sunny Singh, author of A Bollywood State of Mind, has no doubts about Sholay’s place in world cinema: “Sholay is a masterpiece of cinema. And that is not only talking about Indian or Asian or Bollywood cinema — globally, it’s a masterpiece. It is politically complex and raises a lot of social issues like the culturally powerful cinema of Kurosawa but at the same time, it’s got that Spielberg touch.”

Much like the Marvel or Lord of the Rings universes, Sholay has also inspired an industry of roleplay among young fans.

Apsana Begum, the independent MP for Poplar and Limehouse, east London, recalls how she and her siblings would re-enact scenes from the film during her childhood.

“I remember being quite scared of Gabbar Singh,” says Begum. “He’s probably the best character in lots of ways, the charismatic, evil villain. There are parts of characters you recognise in people around you. I can probably think of a few people that are like Gabbar Singh, not going round with a gun, but just characteristics that ring true in real life.

“I don’t know why I ended up as Gabbar Singh. I don’t know what it is about me in that role — my siblings all had fun doing something else. Gabbar Singh was scary. That spontaneity of the villain, you don’t know how evil he is. I feel like, what would the film be without him?”

For a generation of British-Asian men, Sholay represented their first instances of seeing positive brown role models on screen. Aasif Mandvi, actor, writer and former Daily Show correspondent, says: “Sholay was the movie that put Bollywood on the map for this little brown kid in Bradford, growing up in the north of England… it was an image of Indian masculinity that I had never seen before.

“The brown men I was surrounded with were sort of subservient shopkeepers, or they were doctors. They were immigrant dads who had all come to England in the 60s and 70s. That was my image of the brown Asian man. Sholay was the first time I saw an image of masculinity, of toughness, of sexuality, that was dangerous.”

Asma Khan, owner of the Darjeeling Express restaurant in central London, recalls seeing Sholay, aged six, in a cinema in Kolkata, India. “I was completely mesmerised,” she says.

Khan, who rewatched Sholay on a flight recently, laughed when recalling that her family once owned a vinyl pressing of the film’s dialogue. “Every time Amjad Khan’s character says ‘haramzada’ (bastard), my aunt’s father-in-law used to jump out of his skin. He was from Kanpur, a very correct Muslim gentleman, and he used to be deeply offended by that.”

During our interview, Khan spoke of watching Sholay with her sons. “It’s not a particularly family-oriented film. There’s a lot of violence and threats and foul language. Yet it’s still something you can watch with your family. There is almost a kind of universal appeal of Sholay which cuts across generations.”

Newsletter

Newsletter