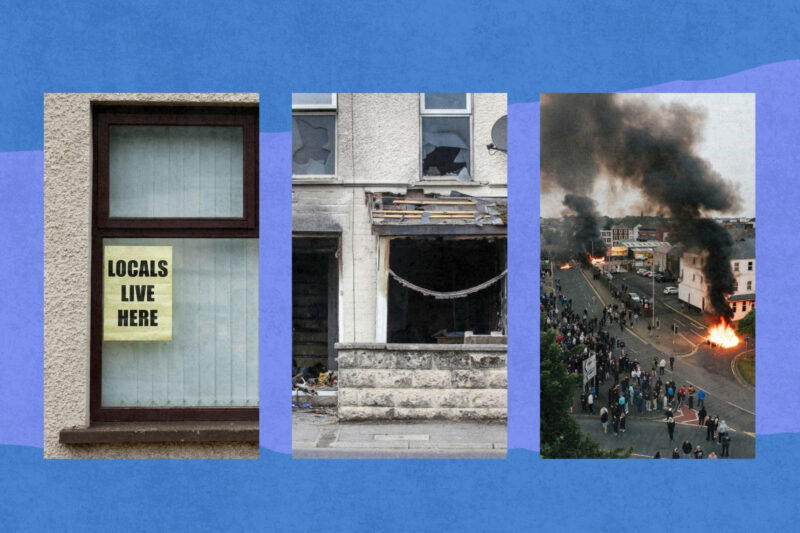

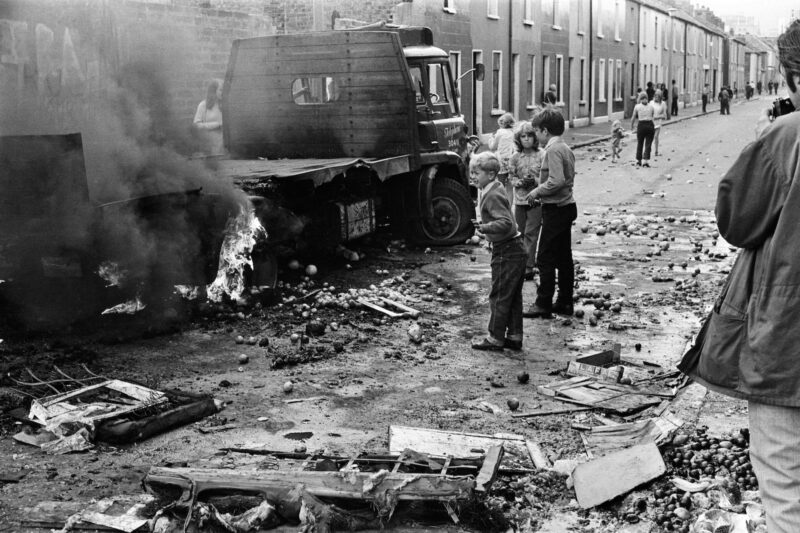

The 2024 riots — by the people who lived through them

From Southport to Belfast, residents remember the violence and highlight its continued effects on communities across the country

On 30 July 2024 riots broke out in the seaside town of Southport, Merseyside, following the murder of three young girls at a local dance class the previous day. The chaos, which began outside the local mosque, was catalysed by false claims circulated online by far-right groups that the killer was a recently arrived Muslim immigrant.

Despite the release of details by police confirming that the attacker, 17-year-old Axel Rudakubana, was born in the UK to a Christian family of Rwandan heritage, anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant violence continued to spread across England and Northern Ireland for the next week.

Stretching from Aldershot to Belfast, the 2024 riots are now considered the worst incidence of racially motivated disorder on British soil for decades. As part of our series of articles on the long-term impact of the unrest, Hyphen’s reporters have spoken to people in communities that lived through the violence and continue to be affected by it today. These are their stories.

The following conversations have been edited for length and clarity.

News from Southport

Imam Adam Kelwick, Quilliam mosque — Liverpool: I was at home watching BBC News when the story broke that there had been an attack in Southport. It was very close to home. Southport is quite near to us. It’s a small seaside town where you never really expect an incident of this nature to happen. Somewhere I take my kids. While I was watching the updates two of the girls were pronounced dead. My 14-year-old daughter walked in and asked, “Dad, what’s happened?” I explained and then she asked why. As a father who’s usually got all the answers, this was a really challenging question…

Imam Ibrahim Hussein, Southport Mosque and Cultural Centre: The Southport murders were [not] of this world. I had never heard of somebody attacking a place where kids are playing, dancing or studying. For us, it was just too much to take. Then, on that very same day, to hear that we were being blamed for what took place…

Jarrar Tahir, business manager at law firm Immigration Advice Service — Oldham: I was working at home when the news came in. I was shocked and sad. As a father of two children, my heart immediately went out to the parents and families. Then, after more details were revealed about the identity of the attacker, I sighed with relief that he didn’t share my faith or background. That didn’t make any difference to what happened later, though.

Amina Atiq, poet, activist and community arts worker — Liverpool: When the stabbings happened, the first thing I thought was: “Are the kids OK?” That’s a natural response for anyone. Then, because it happened so close to home it was, “I hope it’s not a Muslim who did this”, because then we’d have to start those conversations again — we’d all be asked to go out and apologise for it somehow.

The Muslim community had nothing to do with the attack. We as individuals and as a collective are not responsible… The only questions we should have been asking were about the safety of the children, the dance leaders at the youth club, how people were doing, the mothers, the parents… It’s sad that, as a society, we have come to this.

Violence spreads

Adam Kelwick: The riots began in Southport and we knew a couple of days in advance that a protest was being organised outside our mosque in Liverpool. People sent me flyers about it. My response was to put out a video message reassuring everybody that if anybody came to our mosque then they would be treated as guests.

I’ve got experience of interacting with people from the far right and Islamophobes through my work with the Light Foundation. That put me in a position to understand that there was another way we could deal with it: going out, meeting and interacting with the people, having conversations and listening to them. That was the approach we decided to take.

It took three hours before the police allowed us to reach out to the protesters outside. It was a mixture of me standing at the doorway and looking out onto the street in disbelief — all these people, the lines of police, the police helicopter and the reconnaissance plane flying above. I was like, “Is this real? Is this really happening?”

Jarrar Tahir: I wasn’t working on the premises at the time, but when the violence started to be directed at local businesses in Oldham and at immigration law firms around the country I became aware of a post on Facebook that said protesters were going to our firm’s head office. When that happened, I was so concerned for the safety of my colleagues working there. It was completely out of order to do that. Immigration lawyers are only doing their job and upholding the law.

Mohammed Idris, businessman and cafe owner — Belfast: A few days after I saw the Southport attack and riot on the news, I saw there was a plan for riots around the country and that Belfast was listed. We were very worried, but I didn’t think it would be massive. Even when I saw that rioters in the Midlands were very, very aggressive and tried to burn hotels housing asylum seekers, I was still thinking that Belfast was not going to be as dangerous.

We had messages from the police and the mosque that there would be a protest… At that time, I was thinking they would just shout and go towards the mosque, that they just wanted to send a message. It was a Friday. I opened my business as usual… The police closed the road to the mosque… They should have closed other roads too because they knew our area would be in danger [and] they know my business because I’ve been raising my voice against hate crimes… When the rioters came, they attacked my cafe. I was inside the office upstairs on the first floor. From the window I could see everything. I even heard them shout my name: “Where is Mohammed?”

Amina Atiq: I work a lot in the culture sector and, as you know, [Spellow library in the Walton district of Liverpool] was burnt down. When that happened, I was like, I have no idea why a library has been burnt down. I mean, what did books ever do to people? It was really sad, because libraries have been hit by a lack of funding and they’re places of opportunity for people.

Ayyan Nomani, president of the Islamic Society at Queen’s University Belfast: It’s misplaced anger. What did a local shopkeeper do to be on the receiving end of such hate, bigotry and violence? He’s there adding to the British economy. Now, these people are coming with whatever twisted ideology they have and just taking it out on them.

How it happened

Ayyan Nomani: The social media accounts that spread misinformation about the Southport attacker being an illegal immigrant and a Muslim are at the very core of what happened last summer. But you can’t look at this incident in a vacuum. What I mean by that is that you have legacy media companies such as the BBC, Sky News and even American news channels that have been constantly propagating the idea of Islam being synonymous with terrorism for years.

Jarrar Tahir: A large number of people from Oldham stood outside our offices to protect us against any potential rioters, but we’re still hearing about cases of racism today. These problems are only exacerbated by the current political conversation about illegal immigration and all the propaganda you still see about halal meat and the burqa.

Amina Atiq: The way the riots started is connected to the political atmosphere in the UK at the moment… A lot of people are looking for where they belong in politics… Before, there used to be the left, the right and the middle, but now it’s like the right-right with the Conservatives and the right-left with Labour.

I think there is a kind of identity crisis in the country, in the white working class. People are fed up. My question is why is it only the white British community that gets to be angry? I’m angry that our children no longer get to be safe in their communities too… Still, whenever I hear of anyone being groomed into the far right, I always ask myself about the state of that person’s mental health… There is a dark web online that I think is a serious concern, but it’s also like we’re not asking a lot of the right long-term political questions about people’s lives.

Alfie Patel, restaurant owner — Southport: The rioters were a thuggish minority who mainly came to Southport from out of town. The people here are very supportive and diverse. I’ve been here for nine years and 99% of my customer base is non-Muslim. Unfortunately, though, everyone gets tarnished as the same.

Adam Kelwick: Rumours were being spread that the attacker was a Syrian refugee who just arrived on a dinghy, which turned out to be complete lies. Then things just escalated… It was a really really intense time… Now, the political and media machine has just gone back to its default of pumping out rubbish about Muslims.

It’s frustrating to see and it does sometimes feel like you’re swimming against the tide, but it’s never a reason to give up. It can be tiring because you’re up against very well funded bodies, thinktanks, political lobbies and parties, but at the same time you do still have the ability to change things. In a sense, the more ignorance that is put out there about you, your community and your religion, the more opportunity there is to break down barriers and have discussions with people who have bought into those narratives.

The aftermath

Ibrahim Hussein: I am just one person, but I lead a group of people [at Southport Mosque and Cultural Centre] who bring their kids here. It’s where their wives come in to pray. The Muslim community here is very small, so to come under this vicious attack, I worry for them all now.

Mona Fadul — Rotherham: After the riots, I thought about moving to another country where I have some relatives, but six months later, I think things have changed. Now, everything is good. I have good neighbours. People ask us how we’re feeling and if we feel safe and they’ve encouraged us to stay.

Annie Sabah — Rotherham: My parents were very scared. My mum’s a housewife and my dad’s worked all his life. After the riots, my mum was scared to go out because she wears a hijab… Over time, things have got better for my dad, but mum is not as outgoing any more. She still holds that fear.

Abrar Javid — Rotherham Muslim Community Forum: Honestly, I don’t think the country’s leadership has done enough to bring communities together or heal the divisions… The riots here happened in a predominantly white area and no one has made any real effort to reach out to those communities, speak to the youth or engage with schools. I’m happy to do it, but it shouldn’t be left to me. These things need to be done at an institutional level. Unfortunately, that’s not happening.

Adam Kelwick: I’ve built some genuine relationships with people because they were involved in the Liverpool protests and riots. The knock-on effect of that is that I think we’ve managed to get through a lot of the ignorance that was spread during the summer of 2024. That’s something I hope to continue and build upon.

The main way to do that for me is going back to the biography of the Prophet Muhammad, peace and blessings be upon him, and seeing how he did this day in and day out. People would come to him, they’d make accusations, they spread lies, attack him verbally, physically. His response was always the most honourable one. Not only would he respond with positivity, the goal was never to prove to anybody wrong — it was to take the other person by the hand and go together towards what is right.

Where do we go from here?

Annie Sabah: It still feels like yesterday. It doesn’t feel like it’s been a year. You just get on with it, but there’s still definitely still a sense of fear in people. We’ve experienced racism before, but the riots made it extreme… The lasting impact has mostly been emotional. There’s a hesitance that’s always going to be there.

Mohammed Idris: The majority of people in Belfast are very kind and supportive. But racism is going up. Now, we are seeing a new racist incident every day, either on business, homes or on people in the streets. The perpetrators feel empowered because the police don’t do anything and the government does not discuss any serious agenda to tackle it.

Adam Kelwick: All the ingredients are in place for more riots and chaos because of the kind of political narratives that are out there… But there is one thing that can defeat them — being a nice person and helping others to become nice people too… You need to be very, very patient and make sure that you’re going to be able to tolerate really nasty things being said. It’s hard, but if you react that way, the other person will see praiseworthy qualities in you, your family, your community, your mosque, your religion, your God, your prophet. That can be enough to transform somebody.

Ayyan Nomani: Every time an incident like this happens, I find myself coming closer to Islam. The simple reason for that is because we know Islam is the truth. It says in the Qur’an that the falsehood is bound to perish by its nature. Whenever something like this happens, it strengthens our brotherhood and it brings us closer together. In the wider community — not just Muslims — I think people are starting to wake up and are becoming desensitised to [what they see in the press] and social media.

Jarrar Tahir: We all need to understand that multiculturalism is embedded in the UK. People need to accept that. Ethnic minorities play a key role in society today. We all need to learn to be patient and wait until the facts are in before making judgments. The UK has a legal system that needs to be abided by. We need to let the law do its work… The majority of people who come to this country legally, pay their way, respect the laws of the land and live peacefully.

Bilal Olama, seeking asylum — Rotherham: During the riots, I had safety concerns. I stayed home for a long time and didn’t leave the house — it lasted for more than 10 days. But, gradually, the situation started to improve, and I began to feel safer. Now, I feel safe in my lovely town, Rotherham.

Amina Atiq: It might sound negative, but I’m not going to paint a picture of hope when I don’t feel very hopeful… The only way out of this is education. When I say that I’m political, I’m political in a way that’s practical. Everyone can be an activist in their own way, whether that’s through words or direct action or some other way. For me, it’s all about education. That’s how I do it every day. Earlier today, I was sitting in a school, working with young people. It was lovely, getting them to look at what equality means to them. I got them to think about what their ideal school would be and they all came up with great ideas. For me, that’s where the hope is… I think, at the moment, as a society, we’re spending a lot more time talking about each other than with each other. I’d rather be talking with each other.

Ibrahim Hussein: After the riots, we put right anything that was wrong with the mosque. People got in touch with local businesses in Southport and asked for fences and bricks and sand and cement for us. They changed the broken windows. People stood with us and told us they were with us. This gives you a warm feeling that you are not entirely in a place burning with hatred.

Newsletter

Newsletter