A capsule in time: Marina Tabassum on her design for the Serpentine Pavilion

The Bangladeshi architect designed this year’s installation in Kensington Gardens, making something timeless that reflects her homeland’s transitory and evolving landscape

When architect Marina Tabassum began conceptualising her design for the 2025 Serpentine Pavilion, A Capsule in Time, she turned to an element typical of the landscape in her native Bangladesh. The shamiana, a tented bamboo pole structure popular in South Asia, became a useful reference point.

Tabassum conceived of the shamiana as a kind of makeshift pavilion, emblematic of the subtropical Bengali context, through which light can penetrate and air can flow. “From my childhood, I remember seeing them and being in them during weddings,” she says. “There was always this beautiful light coming through the colourful fabric.”

Designed with a desire to capture that ethereal quality of light, the pavilion consists of a translucent polycarbonate facade placed between four timber capsule segments that can be connected to create an enclosed space. On view for only four months in Kensington Gardens, west London, the structure has a temporality that speaks to an interest at the centre of Tabassum’s own practice: the relationship between architecture and time.

“Architecture has always been a tool of continuity,” she says, referring to mausoleums, pyramids and mosques that serve as the material remnants of a legacy. “But we come from a land in Bangladesh where it’s very ephemeral. It’s also very transitory because land is constantly changing, shaping and reshaping itself. Because of that, people are constantly moving from one place to another. Your entire dwelling is moving from one place to another.”

As the principal architect of her eponymous practice in Dhaka, Tabassum has designed modular structures of bamboo and steel for landless populations residing in the sand beds of the Meghna, Jamuna and Teesta rivers, which can be transported and reassembled during flooding. She is the recipient of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, the Soane Medal and the Jameel Prize, among others. For the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2018, she created an installation in collaboration with local villagers living near the Panigram Eco Resort in the Ganges delta. A Capsule in Time is her first building outside Bangladesh.

One of her first encounters with the profession was a trip to Bangladesh’s modernist parliament building, designed by the architect Louis Kahn in the 1960s. “I remember vividly going into that ambulatory and then going into the parliament chamber. It was very surreal,” Tabassum says. “When I started looking into architecture, [the memory] triggered back. Oh, this is architecture. This is what architecture really looks like.”

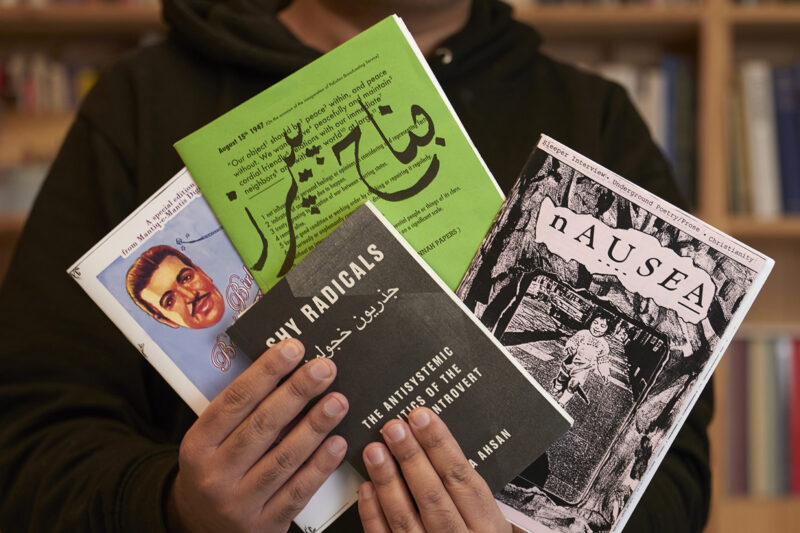

As a student at Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology, Tabassum was drawn to the works of local architects Muzharul Islam and Bashirul Haq, though the focus was largely eurocentric at the time. “We were more interested in what the foreign architects, let’s say, the western architects, came and built in Bangladesh,” she says, referring to the works of Constantinos Doxiadis and Paul Rudolph.

It was after graduating from university that Tabassum began to develop her own style, looking into the archaeology of the local landscape — Buddhist monasteries, Hindu temples, mosques from the Sultanate period, Mughal architecture, even colonial buildings that addressed issues of climate. “You start to draw on ingredients to create your own language. Once you finish your education, you do a lot of unlearning to relearn certain things,” she explains.

In the 1990s, as Tabassum began her practice, real estate developers in Dhaka began to commission lucrative projects involving the construction of glass and concrete buildings. Tabassum was offered 30 projects at once but was uninterested in the briefs, which seemed formulaic and invested only in creating a product where every square inch was “numbered with a price”. She was initially a founding partner of the firm Urbana with Kashef Chowdhury before establishing Marina Tabassum Architects in 2005.

Tabassum began to articulate a design philosophy rooted in a collaborative approach with stakeholders and community members, taking into account a site’s cultural context and history. Her passion lies in creating public projects. “I like to see people coming into the buildings or spaces, how they react to it,” she says. “It is almost like a platform where people perform.”

The light-filled, exposed brick Bait Ur Rouf mosque, eschewing the archetypal dome and built on a parcel of land once owned by Tabassum’s grandmother, serves a rapidly growing community in a northern suburb of Dhaka. The exhibition areas of the Museum of Independence were built underground in order to preserve the green spaces in the public square where it is situated.

Tabassum notes how contemporary Bangladeshi architects are increasingly interested in developing a vernacular style, rather than modelling works on trends abroad. “I think there is an understanding that you cannot follow the west because it just doesn’t make sense,” she says. “The younger generation, they understand the climate. They understand rootedness. Everybody’s striving for something that would be a balance between what is modern, but, at the same time, has a root in the country.”

In the middle of the courtyard within the structure at the Serpentine is a ginkgo tree. It is aligned with the bell tower of the Serpentine Gallery and forms a visual focal point at the centre of the pavilion. “I think it’s about this whole notion of time and continuity,” Tabassum says. “The ginkgo tree is one of the oldest trees in the world that has survived.”

Once the pavilion is taken down in October, Tabassum’s hope is for the structure itself to perhaps serve as a library elsewhere and for the tree to be replanted in Hyde Park. “I thought that was a beautiful, poetic way of bringing a sensibility of the pavilion [into] the park,” she adds.

The gingko’s presence, Tabassum suggests, moderates the structure’s grandeur, an element that perhaps reflects her practice’s own impulses: to create something timeless in a landscape that is transitory and evolving. “The tree actually gives you a scale where it’s much more intimate. So there is an intimacy, but then again, there is a monumentality. It is oscillating between the two.”

Newsletter

Newsletter