William Tell is a bold and radical retelling of the Swiss legend

Nick Hamm’s new adaptation should be praised for its diversity and its reminder that violent occupation knows no borders

William Tell is a household name in many respects, but very little specific information is known about the Swiss folk hero. For one, we don’t actually know if he was a real person who fought in the Crusades, battled the occupying Austrian empire in the 14th century or was ever forced by its tyrannical leaders to shoot an apple off his son’s head. There are those who believe he did exist or is an amalgamation of different figures, while others think he was purely a fictional character created to inspire people living under violent occupation.

Throughout the centuries, the legend of William Tell has been depicted in plays, books, operas, songs and paintings. Now it has arrived in the form of Nick Hamm’s new epic starring Claes Bang (Dracula, The Northman) in the titular role.

William Tell may be as Swiss as a wheel of gruyère, but what is so refreshing about Hamm’s action feature is that he introduces multiple elements from the Middle East, beyond Tell’s origin story fighting against Muslims in the Crusades. The film presents Tell scarred by the horrors of war, paralysed by violent flashbacks of the death and destruction he witnessed in Jerusalem. This adaptation centres on the story of Tell turning on his own in order to save a woman named Suna who is under attack from European soldiers.

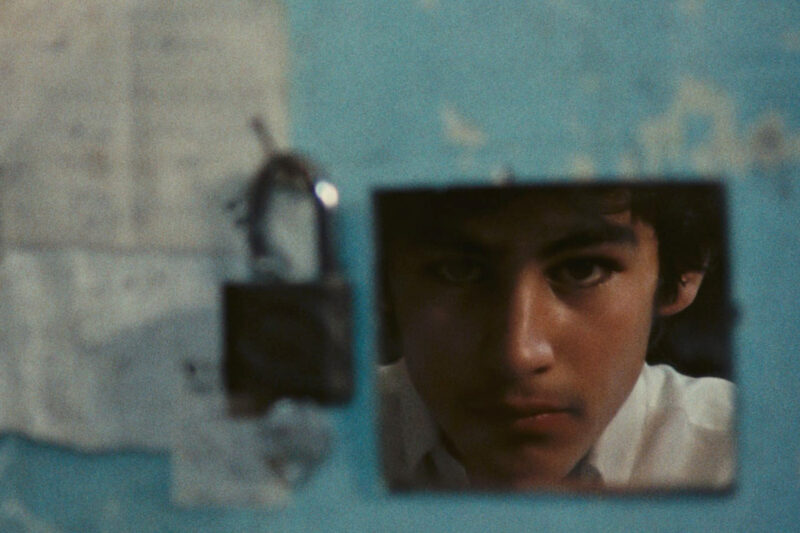

We meet Tell as he returns to Switzerland as a staunch pacifist and starts a family with Suna, his now wife, played by the astonishing Iranian actor Golshifteh Farahani (The Patience Stone, Paterson).

It’s a radical departure from the previous depictions of Tell’s wife, usually presented as a white Swiss woman named Hedwig who stays out of the action or cowers on the periphery as her husband takes aim at perilously placed fruit. In Hamm’s version she’s a far more formidable force, showing great wisdom and impressive fighting skills, and symbolises a hope for the future where love can still blossom, even after the horrors of war.

Farahani’s role is far from tokenistic casting and, instead, brings a fascinating dynamic to Tell and Suna’s relationship. Her character is in large part the reason why Tell, despite his hatred of violence, feels compelled to take up his crossbow against the Austrian occupiers, led by the dastardly Gessler (Connor Swindells).

Farahani’s Suna is an equal to Bang’s Tell — both in her performance and her character development. Indeed, the Persian actress, having grown up in Iran during the revolution, seems to have a profound connection to the material, not only because she witnessed how seismic revolution can affect a homeland, but because — as the film continually reminds us — war is a hell from which no one emerges unscathed.

In Hamm’s adaptation, he reminds us of the historical truth that there were different races, religious sects and orders across the European continent all those centuries ago. The character of Furst, for example, is played by Amar Chadha-Patel (The Creator, Dashcam) as a highly skilled warrior from the Middle East — though he’s often depicted as a Caucasian character, typically a Swiss Catholic priest. Furst instead becomes a key figure in Tell’s group of fighters who rise up against the Austrians, his combat style markedly different and with clear influences from Middle Eastern and Asian martial arts.

When Suna and Furst meet in the market there is a small but touching moment when the two non-white characters greet each other in Arabic. Both prove to be inspired casting choices and wonderful performers, showing that diverse representation is actually an opportunity to enrich a story, bring in new perspectives and symbolism, and have your actor’s race become a source of inspiration for their character.

While internet trolls tend to freak out at the mere suggestion of a traditionally white role being played by a person of colour (the recent online backlash to Paapa Essiedu’s potential role as Severus Snape in HBO’s forthcoming Harry Potter series was deeply depressing), Hamm’s film is a reminder of just how powerfully and seamlessly you can breathe new life into a story by reimagining its origin.

For a tale that’s been adapted so many times, it is still a total thrill to watch William Tell shoot that famous apple. But, really, it’s the new elements of Hamm’s film that work best — its diversity, the depictions of the ignoble nature of war, how violent occupation knows no borders and that, unfortunately, all these centuries later, history continues to repeat itself.

William Tell is now showing in UK and Irish cinemas.

Newsletter

Newsletter