Shift to e-visa scheme could strand people abroad after 31 December 2024

Most UK biometric residence permits expire in December. But some are struggling to apply for digital replacements — with the less tech-literate particularly at risk

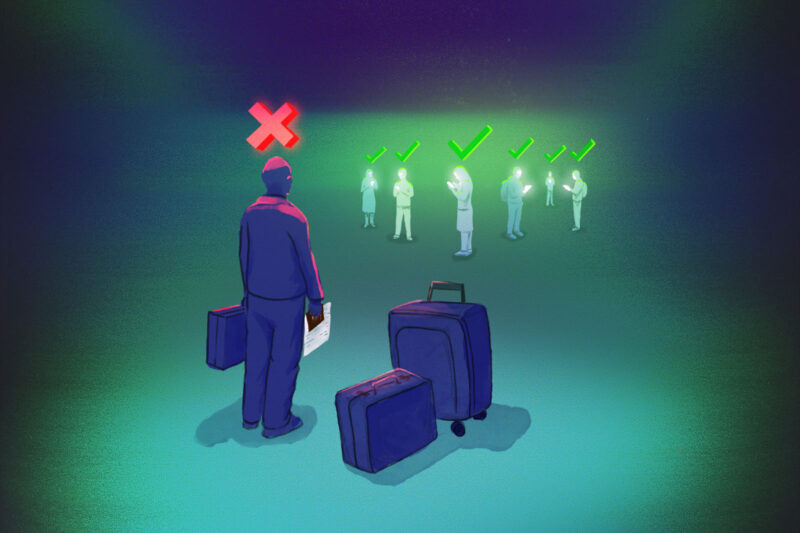

Thousands of older and less tech-literate people could end up stranded abroad if they leave the UK after 31 December 2024 because of the transition to a new digital visa system, campaigners and an MP have warned.

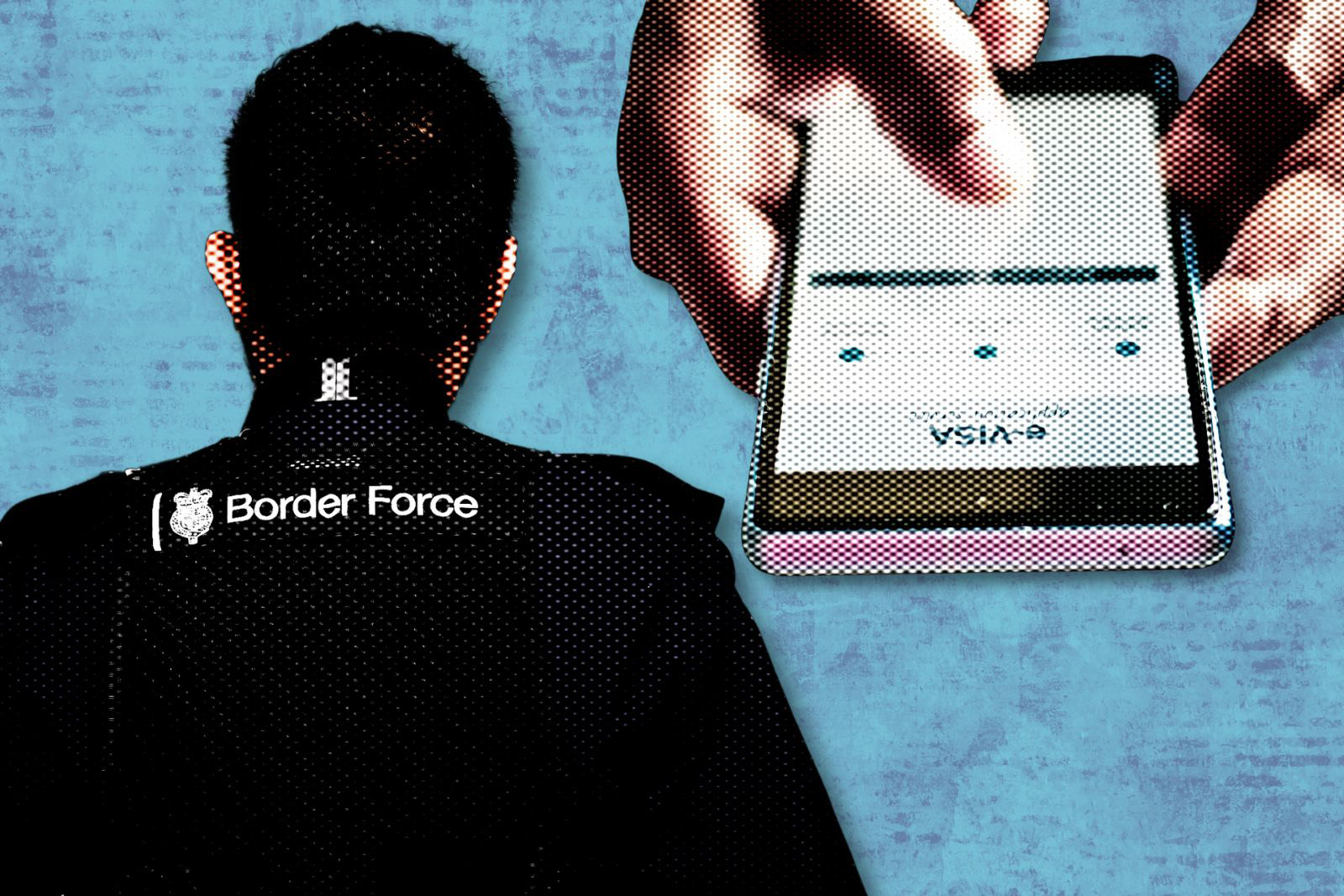

The government’s e-visa scheme, announced in October 2023, replaces migrants’ physical papers — including biometric residence permits (BRPs) and legacy documents such as passport stamps — with an online status. These documents are critical for proving the right to enter the UK, work, rent and access public services.

Most BRPs will expire on 31 December, according to the government, and can only be replaced by e-visas. The new scheme will affect more than four million people, according to migrant organisation the Helen Bamber Foundation, including refugees, short-term residents and 200,000 older people with decades of residency in the UK who are still in possession of legacy documents. The Home Office declined to say how many people in the affected cohort still had yet to apply for e-visas, in response to a request for information by Hyphen.

A briefing on the scheme from the House of Commons Library warns that: “Getting an e-visa is not compulsory as such, but failure to get one carries major risks, especially for international travel.”

It adds: “Someone whose permit expires on 31 December 2024 should not leave the UK and attempt to return after that date unless they have set up their e-visa, as they may be unable to return … Somebody who attempts to return to the UK in 2025 presenting only an expired residence permit might be denied boarding even if they do have valid immigration status.”

But the scheme has had technical issues and could exclude people who do not have a smartphone or sufficient data on their phones, or whose English is not good, campaigners warn. Applicants need to have at least an iPhone 7 or an Android phone with contactless payment — because the process, which has more than 20 steps, includes taking and uploading photos and scanning the electronic chips that are commonplace on some forms of ID.

Like many other refugees in the UK, Sara — who asked us not to publish her surname — has found herself having to adapt to a constantly shifting landscape when it comes to proving the right to live and work in the country. She described the application process for the new e-visa as “challenging even for tech-savvy” people.

“It feels designed to put people who have the right to live in the UK in constant fear and uncertainty,” she told Hyphen.

After setting up e-visa accounts for herself and her son, who also has the right to remain in the UK, Sara received confirmation emails instructing her to check and preview the details and link them to their passports. But after inputting her details, she was taken to a page — seen by Hyphen — that read: “We cannot show proof of your status.”

Sara’s 16-year-old son is currently at school in Egypt and plans to return during the Christmas holiday. But his BRP is set to expire at the end of November, and Sara is worried that the airline in Egypt may refuse to allow him to board without an e-visa.

Liverpool Riverside MP Kim Johnson, who hosted an event last month with the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants on navigating the UK’s immigration system, said she was concerned about a lack of awareness from her constituents around the deadline for the transition. “Without adequate safeguards, the system change to e-visas could lead to widespread disenfranchisement and hardship for those who lack digital resources or assistance,” she said.

She added: “I will be doing work to increase awareness for residents who are at a disadvantage as they may struggle to navigate the entirely online process or face barriers in accessing necessary support.”

A report published in October by the digital freedoms organisation Open Rights Group criticised the lack of languages offered by the e-visa platform. It also said no provisions had been made for people with mental health challenges, such as those who have survived torture or fled war, or who simply struggle with digital literacy.

What’s more, the group has warned that e-visa users must be connected to the internet in order to generate their immigration status in real time, every time they need to prove it, which could cause issues in places where the online connection is unstable — such as international airports.

Labour MP Bell Ribeiro-Addy — one of 25 Black, Asian and minority ethnic MPs who last month urged home secretary Yvette Cooper to ensure that “another Windrush scandal cannot happen again” — told Hyphen: “The shift to e-visas seems full of potential glitches. This risks further alienating long-term UK residents. We know digital applications can be a significant barrier, which would impact elderly and long-standing migrants the hardest.

“The painful legacy of the Windrush scandal is still fresh and much of the hostile environment legislation remains intact. We must learn from past mistakes, with practical support and a review of the transition period. Residents could too easily find themselves unable to work, vote or travel freely.”

The Home Office was forced to release a critical report in September that concluded that the origins of the “deep-rooted racism of the Windrush scandal” stemmed from the fact that “during the period 1950-1981, every single piece of immigration or citizenship legislation was designed at least in part to reduce the number of people with black or brown skin who were permitted to live and work in the UK”.

E-visas were first rolled out to EU citizens in the UK in the wake of the 2016 Brexit referendum. Grassroots group The 3 Million helped them apply, and told Hyphen it had been beset by problems — including reaching people in marginalised communities and those who did not have access to smart devices or the internet. In July, the group said more than 137,000 applications from EU citizens were still waiting to be reviewed.

The group has helped set up a website for people to log issues with the process this time around. It said reporting of problems has increased since the Home Office launched its communication campaign in August to urge people to apply before the end of the year.

Problems reported to the group have included the Home Office e-visa page showing old, expired visas for people whose applications have been granted. People in the gig economy have been disproportionately affected as they are often asked to prove their right to work and can lose out on income if they cannot do so quickly. Other issues reported include technical glitches, one of which allegedly took multiple months to resolve.

A Home Office spokesperson said: “E-visas bring significant benefits. They cannot be lost, stolen or tampered with, unlike a physical document, and also increase the UK immigration system’s security and efficiency.

“E-visas have been tried and tested over several years, and millions of people in the UK already use them to prove their immigration status.

“Most people who create a UKVI account to access their e-visa will be able to see their status right away, and those who can’t can continue to use their physical document in the meantime. The Resolution Centre offers support for those who need to prove their status and are unable to.”

The UK Visas and Immigration Resolution Centre can be contacted on 0300 790 6268. For more information on who is affected by the scheme go to https://www.gov.uk/eVisa.

Got a story about visas or immigration? Contact info@hyphenonline.com.

Newsletter

Newsletter