Azad Essa Q&A: ‘When I went to Palestine, I immediately saw the similarities with Kashmir’

Azad Essa’s latest book, Hostile Homelands, attempts to spotlight an alternative narrative to world events. Photograph courtesy of Azad Essa

The South African journalist and author examines the links between Israel and India, and how his heritage informs his work

Journalist Azad Essa was born during the end of apartheid in South Africa. Growing up, he recalls being very aware of the tides shifting, and the impact of a new social order on both individuals and the collective.

Essa started his career covering global social justice movements, with a specific focus on Kashmir due to his family’s own Indian heritage. Currently a senior reporter at Middle East Eye, he is based between New York and Johannesburg. His work tackles foreign policy and Islamophobia in the US, but he has also written books addressing the issue of race and identity within world politics.

Essa’s latest book Hostile Homelands: The New Alliance Between India and Israel, was published just months before the Hamas attacks of 7 October and Israel’s ongoing assault on Gaza. Rooted in the history of India’s partition, which occurred only nine months before the birth of Israel, the book attempts to spotlight an alternative narrative to world events.

He speaks to Hyphen about the parallels between Palestine and Kashmir, the growing partnership between India and Israel and how his own background has informed his reporting.

What motivated you to pursue a career in media?

I was brought up in a South Africa that was changing. As a teenager, I noticed the shift that took place, and I was a product of that. For instance, I was part of one of the first groups of kids that joined a former white-only school.

Growing up in South Africa as it entered the global community after being isolated for so long, news became a very important part of your life. You’re living through history, but then you’re also witnessing and reading about it.

I saw how important the media was in telling the story, in defending a situation and even in stirring the pot in terms of misinformation. I was very much drawn to the idea of being able to tell the correct story, as well as stories that were not being told, because you could see the devastation it would create if the media were not doing their job. I wanted to be part of shaping that narrative.

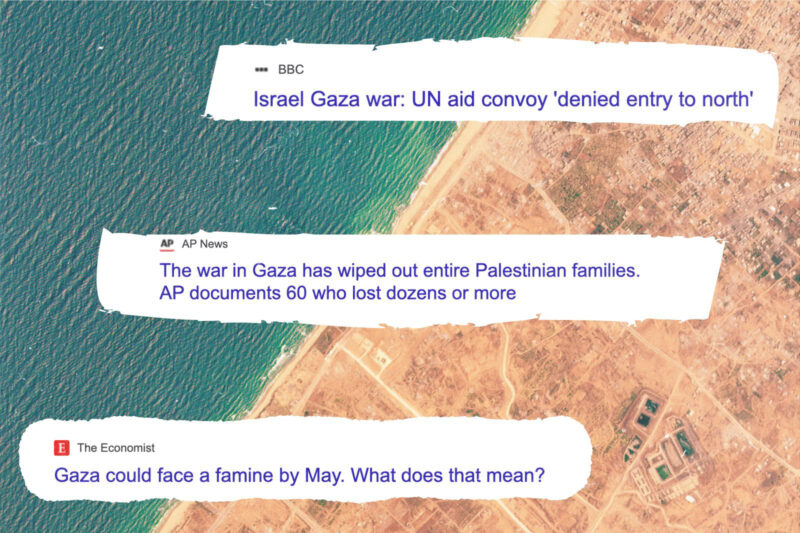

Misinformation continues to be a huge problem — how do you reflect on the coverage of recent world events?

Media often focuses on the narrative of the state. For instance, Indian media has been filled with disinformation about what happened on 7 October. It has underplayed the devastation that Gaza has faced, framing it as a necessary war for the Israelis.

It has also been tone deaf in the way that it has presented the opportunities India has gained and benefited from over the past 12 months — the jobs that Israel has offered to Indians, the arms contracts that have been given.

For me, objectivity is no longer the most important thing. The most important thing is the stance that you take, and whether you’re standing up to the powers doing the oppressing.

Your book Hostile Homelands traces the relationship between India and Israel. What’s the first thing we should know about this topic?

The narrative we’re given is that in 1947 the Muslims wanted their own place, and as a result there is this partition of India. No one tells you that actually India wasn’t a place where everyone was living happily. There are distinct regions with different cultures, politics and identities — Pakistan was just one element of that, and even then we’re not told the full story. Even today, there is a cognitive dissonance when it comes to India, and a refusal to see the country for what it is, and what it’s possibly becoming.

For example, in 2014 when Modi came into power, suddenly the relationship between India and Israel became more public. Then, in 2019, India essentially annexes Kashmir. They cut off communication, arrest thousands of people and dismantle all efforts to resist. Later, the Indian ambassador to the US makes a statement saying that they’re going to build settlements in the territory, just as Israel has built settlements in Palestine.

When he said that, it basically crystallised that all this stuff I had been observing needed to be written and explained. How is it that a country that was supposedly standing for Palestine could suddenly talk about emulating Israel? That’s the answer I went in search of with this book.

You’ve reported a lot on Kashmir, a region that continues to see conflict and occupation — what drew you to that story and how does it relate to Palestine?

I grew up with this idea of India as a bastion for the global south. When I started learning about the story of Kashmir in the early 2000s, I was very shocked by what I discovered. I just couldn’t believe that India was conducting its own form of occupation, and that led me down a rabbit hole. Eventually, I went to Kashmir and saw the reality for myself, but I faced a lot of pushback in my reporting of the region. Similar to me, a lot of people had a certain idea of India that didn’t match up to reality.

When I went to Palestine over a decade ago, the similarities were plain to see in terms of how people’s movement was being controlled, how economic bubbles were created. In many ways, that’s where my education on Palestine began.

As a person of Indian origin, I see how India is now invested in that occupation. Over the past year, some Indian universities have also increased their relationships with Israeli universities, while students elsewhere are calling for divestments, getting suspended, arrested and sprayed with skunk water.

How has your personal background informed your work?

As a South African of Indian origin, it’s impossible to escape the hyphenated identity. Post-apartheid, race and ethnicity were still a big deal and continue to be. I would spend a lot of time with my grandfather, so I was continuously filled with stories of the past, about Empire and colonialism, why my grandparents came to South Africa and the role of Gandhi.

Then when I visited Tel Aviv, I remember going to a beach and watching how people were swimming. I felt as if I were a European who had travelled to apartheid South Africa, to a beach where the local Black or brown people could not go, despite living in the vicinity. It felt like it was almost an injustice for me to be at that beach. I couldn’t shake off that feeling. It stuck with me for a long time, and still remains.

It made me think a lot about borders, passports and visas. It spurred me to look into these topics in a way that wasn’t necessarily being spoken about, to look at them from my angles and experiences.

Hostile Homelands is published by Pluto Press.

Newsletter

Newsletter