‘We support Palestine for the same reason we supported Nelson Mandela’

Pro-Palestine campaigners take inspiration from the anti-apartheid movement. Liverpool’s multicultural Toxteth is home to veterans of both

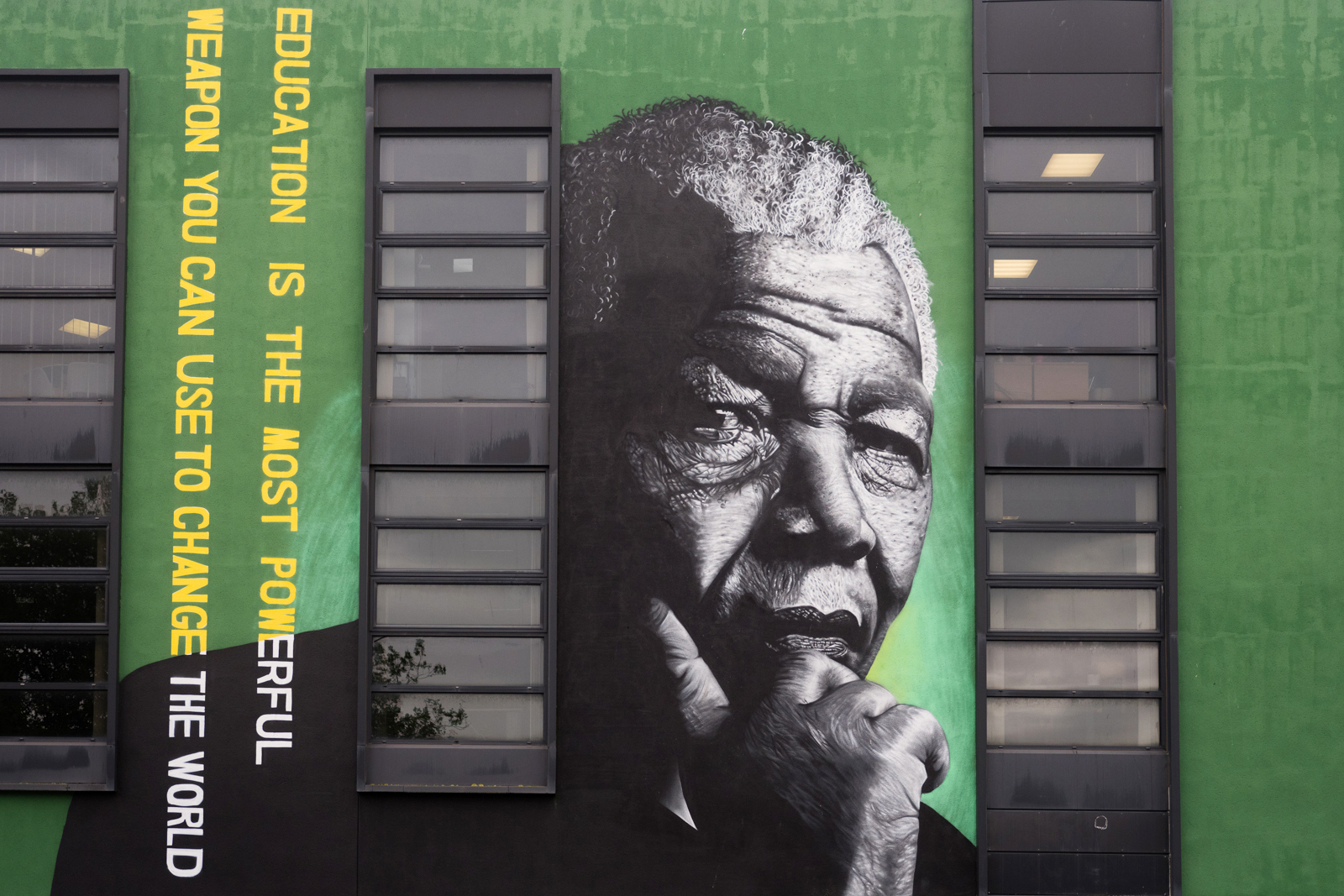

A two-storey mural of Nelson Mandela on the side of the Kuumba Imani Millennium Centre lets you know you have arrived in Toxteth, a few minutes’ drive south-east from Liverpool city centre.

For decades, this working-class stronghold of tightly packed red-brick terraces has ranked among the most deprived areas in the country. It is also home to one of the oldest Black communities in the UK, dating back to the 18th century, and a significant percentage of the city’s Muslim population. A stroll down Lodge Lane, one of the neighbourhood’s main streets, takes you past an array of Syrian patisseries, Afghan grill houses, halal butchers, international supermarkets and multicultural community projects.

The area’s anti-racist roots run deep, says Sonia Bassey, chair of the Mandela8 charity, which commissioned the mural by local artist John Culshaw. Last year, the group unveiled a stone memorial to the late South African anti-apartheid leader during a ceremony attended by his family.

Mandela served 27 years in jail for conspiring to overthrow South Africa’s apartheid state, becoming a powerful symbol for international anti-racism campaigners. After his release in 1990, he helped end the brutal system of racial segregation and discrimination that had dominated South Africa since 1948, going on to win its first multi-racial presidential election.

“People in Toxteth were passionate about opposing apartheid because they could see the synergies between what was happening in South Africa and what was happening to them — particularly police brutality and police oppression,” says Bassey.

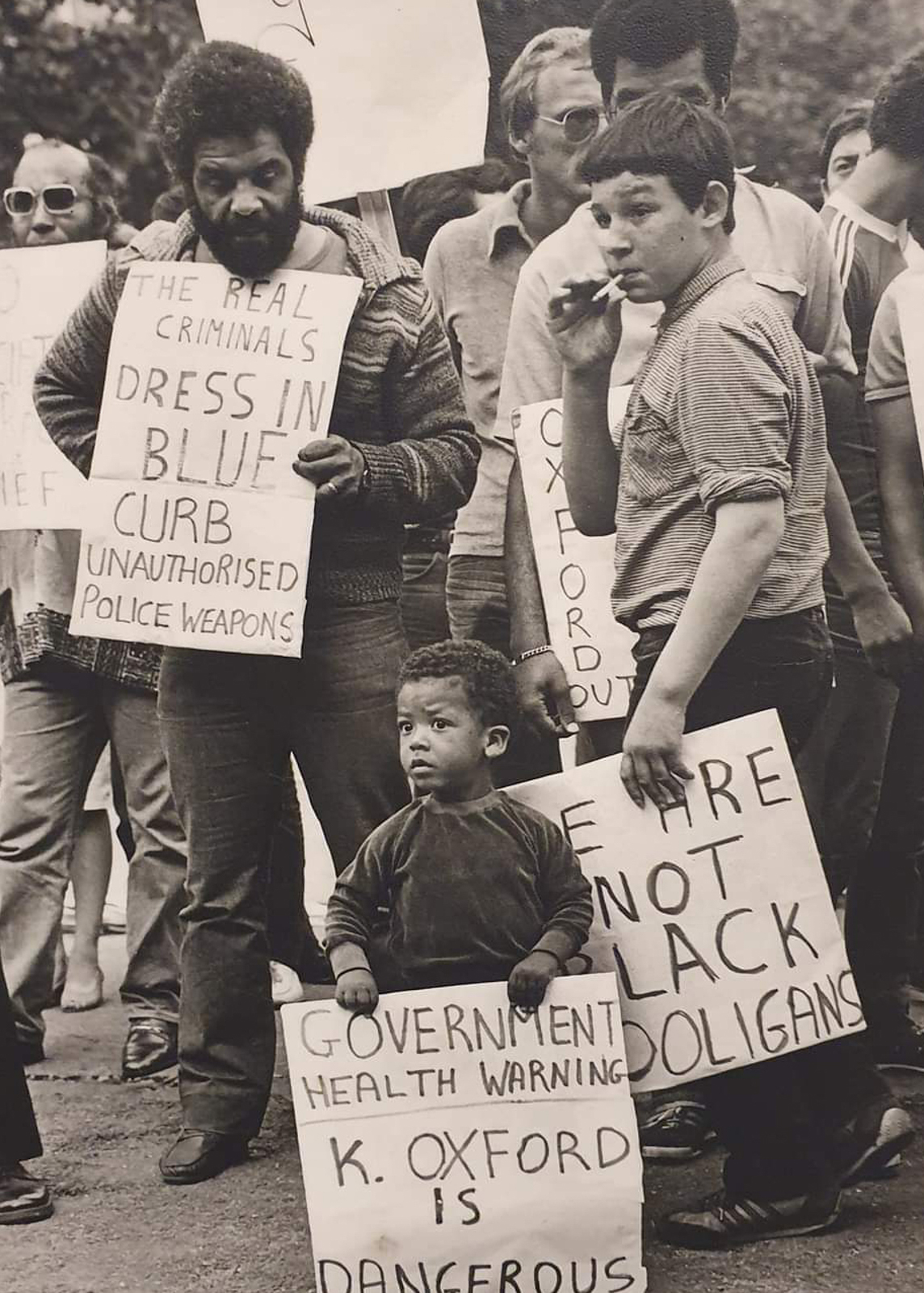

Toxteth and other areas of the UK made national headlines in 1981 when unrest broke out, sparked by longstanding racial tensions and decades of discriminatory policing of Black communities.

“They were experiencing similar things, although on a less horrific scale, but they could relate because they were living in a house that was beyond or below standards,” Bassey adds. “They couldn’t access healthcare. We had things like postcode blacklisting: you couldn’t get a job, you couldn’t get credit, you couldn’t get finance, you couldn’t get a mortgage.”

Liverpool’s anti-apartheid movement led the way for the rest of the country. In 1960, the city council announced a boycott of South African goods, laying the foundations for 21 other local authorities to do the same. Hundreds of students organised a sit-in at Liverpool University in 1970, demanding the end of South African investments and protesting about the support for apartheid previously expressed by its then chancellor Lord Salisbury. In 1987, Liverpool dockers refused to handle uranium shipments arriving from South Africa.

Toxteth’s Black community formed the beating heart of anti-apartheid activism in the city, regularly organising protests as well as cultural events and fundraisers such as the 1988 Mandela Freedom Festival. Bassey’s father Solly, a prominent local campaigner, was arrested in 1985 after stepping out onto the course to disrupt a cross-country race involving the white South African runner Zola Budd. Budd had been granted British citizenship to circumvent the international sporting boycott imposed on South Africa by the International Olympic Committee and other international sports organisations in 1970. Bassey was convicted of causing actual bodily harm to a police officer and fined £50, though this was overturned on appeal.

South African apartheid ended in 1994. But Liverpool’s tradition of international solidarity has continued. Today, it is Palestine whose national flag is plastered in the form of posters and stickers on lamp-posts and dustbins around Toxteth, as well as filling the noticeboard outside the Mandela memorial. Around the corner from the mural in Granby Street, the home of a vibrant Saturday market and one of the oldest multicultural neighbourhoods in Britain, Palestinian flags compete for space with boldly coloured street art as traders sell everything from vintage leather jackets to homemade jerk sauce. In September, thousands of people gathered on the waterfront to protest about the government’s stance on Gaza as the Labour party began its annual conference at the ACC Arena — where pro-Palestinian activists were ejected after heckling speakers.

“This community, for as long as I have known, had always stood firm against injustice and racism,” says Bassey. “That’s why they supported the campaign to free Nelson Mandela. And that’s also why they support Palestine.”

The parallels are easy to draw. The word “apartheid” has gained new currency in describing Israel’s treatment of Palestinians and some campaigners, such as retired lawyer Jeremy Hawthorn, have been involved in both movements. He, however, sees one big difference between his days of activism against apartheid South Africa and the pro-Palestine advocacy he is engaged in now.

“Institutions today are very afraid of being called political,” he says. “We see private companies pulling out of Israel, but they would never say ‘We are doing this because we think it is a racist society, which we disapprove of’. They just make excuses and say they had insurance problems.

“With public institutions, I wouldn’t mind betting that there is a lot of quiet disengagement going on — for example councils not stocking their canteens with Israeli produce — but no one wants to express this view publicly.”

Lila Tamea is a PhD student at Liverpool John Moores University whose research focuses on Islamophobia and Muslim student activism. She previously served as the president of her university’s student union and agrees that institutions such as the National Union of Students (NUS) are much more reluctant to take strong political stances than they once were.

“I think it’s quite sad,” she says. “In the 1970s, the National Union of Students had a very strong anti-apartheid stance and was often openly anti-Zionist.”

The network built in 1971 between the NUS, the anti-apartheid movement and the London-based Committee for Freedom in Mozambique, Angola and Guiné offers one striking example. Together, students coordinated campaigns demanding their universities divest from companies such as Barclays bank, which was lending money to the South African government. By the end of the 1970s, 18 UK universities had withdrawn financial investments in South Africa.

But Tamea says it’s easy to over-romanticise Merseyside’s anti-racist past. “Yes, people here will never buy the Sun,” she says, referring to the 35-year boycott of the tabloid over its reporting of the Hillsborough disaster, which blamed victims. “But they will read the Daily Mail. In many Merseyside constituencies, Reform came second to Labour. The riots last month started in Southport.”

Toxteth is, sadly, no exception. In November, a few months after it was unveiled, the Nelson Mandela memorial was vandalised. Two of the 32 stone pedestals representing figures in a classroom — a reference to the educational work Mandela undertook while imprisoned — were attacked and toppled, with one pushed into the water. The artwork was also defaced with racial slurs.

Soon, though, the damaged pedestals will be replaced.

“The more things people do like this, the more you have to stand up to them and say no,” says Bassey. “I have to keep going — for me, it’s generational. And it’s not that hard, because we stand on the shoulders of giants.”

Newsletter

Newsletter