Why we need to talk about class

Beating an emboldened far right means building bridges and having some difficult conversations

It was a cold autumn evening in 2018 and I was heading back to my house in Coventry. As a second-year student at nearby Warwick University I, like many others, lived in Earlsdon, a residential suburb in the south of the city. As I walked past the terraces of Broomfield Road, I was approached by three shaven-headed white men.

Instinctively, I feared the worst when I was approached, but they turned out to be more curious than hostile. They asked if I was a student and, when I said yes, inquired as to what I was studying, so I told them about my history and politics course.

“What does any of that mean for a working-class idiot like me, mate?” one asked.

I told him that being working class did not make him less smart than anyone else and that he probably had a better understanding of how the world works than most of the kids I was studying with. At the end of the conversation, another said: “You’re sound, mate. Don’t let the Marxist professors brainwash you.”

I laughed to myself. They might not have known it, but most of what they had been saying was more Marxist than anything many of my faculty staff would have come out with.

Every now and again, I find myself wondering how they might have voted in subsequent elections. Tory or Labour? Perhaps Reform UK? Maybe, like a significant chunk of working-class people, frustrated with politicians of all stripes, they haven’t bothered at all.

The thing I remember most about our conversation is that, despite our ostensible differences, we were all able to find common ground quickly, simply by talking as human beings and recognising our shared experiences. That one encounter helped to establish my long-held belief in the political importance of talking to people — even those we might initially disagree with.

Several years later, I discovered that in 1981, on that same road, Dr Amal Dharry had been stabbed to death by a young skinhead in a racist attack. One year before, 20-year-old Satnam Singh Gill had been the victim of a similarly motivated murder.

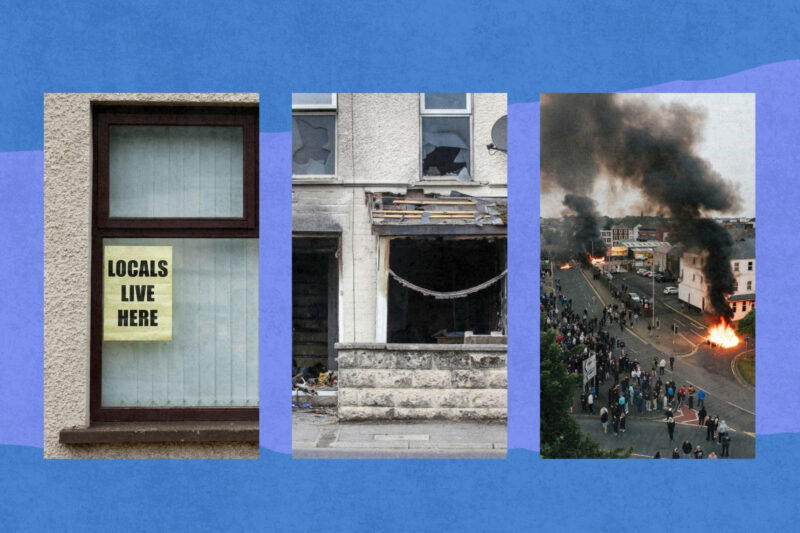

Back then, attacks on immigrant homes, businesses and places of worship were common, fuelled by inflammatory narratives of out-of-control immigration, pushed by politicians and the press. The recent UK riots were eerily reminiscent of that era.

Cities such as Coventry, with large, well-established Black and Asian communities, may have been safer than parts of the north east, Yorkshire, Merseyside and Belfast, where much of the violence took place, but there were real fears across the country. Mosques were bricked, graves desecrated, businesses looted, hijab-wearing women attacked and hotels housing refugees subject to arson attempts.

My initial reaction to the riots was one of fear and anger. I was furious with right-wing politicians, public figures and media outlets for spending years emboldening racist thugs, then pretending to be shocked by the violence or claiming that the people terrorising our communities were driven by “legitimate concerns”.

Then, I pulled back and took another look at what was happening. Watching news footage and videos published on social media, it was clear that the organised far right played a central role in the violence. A significant number of those involved, however, were children and young people swept up in outrage fuelled by social media misinformation.

The way I look at it, teenagers who smash windows and loot businesses in their own communities are invariably teenagers with very little pride in the places they are from and very little to lose. It is no coincidence that seven out of 10 of the most deprived parts of the country were hit by the riots.

Towns and cities such as Sunderland, Middlesbrough, Hull and Hartlepool have long suffered from a chronic lack of investment, high unemployment and worsening living standards. Reform UK, which now holds five seats in the UK parliament, has picked up support in former mining communities and run-down seaside towns — places that once offered strong communities and jobs that could provide decent lives for a family.

Instead of offering solutions to the devastating effects of deindustrialisation, deprivation and cuts to public services, the far and populist right blames immigrants, refugees and minority communities, casting them as the enemy within and making them the target of anger that should clearly be directed elsewhere.

While Black and Asian communities are excluded from the far-right conception of the working class, they are, in fact, disproportionately part of it. British Pakistani and Bangladeshi households also suffer the highest rates of child poverty at 58% and 67% respectively, and women of Bangladeshi and Pakistani heritage in the UK earn on average almost a third less per hour than white British men in similar jobs.

Places famous for their diversity — Luton, Bradford, Birmingham and more — have also been ravaged by deindustrialisation and decline. They too suffer disproportionate levels of poverty. They too contend with the housing crisis. And they too have been failed by successive governments.

The UK working class is and always will be multi-ethnic and multifaith. While some choose to focus on racial, religious and cultural differences, those of us who think differently should be equally dedicated to uniting all of our communities around a universal set of material concerns. After all, racism and the politics of blame are all that the far right has to offer. Embracing such views will not put a roof over anyone’s head, food on their tables or money in their pockets.

Establishing that common ground will mean engaging a diverse range of people and views. It’s not always easy or comfortable, but it’s the only way to win an ideological battle. And sometimes, all it takes is a simple conversation, like the one I had in Coventry a few years ago.

Newsletter

Newsletter