‘It is the politics of visibility’: the community archives saving their histories from erasure

Marginalised communities have long fought to preserve their own stories and provide an alternative to the Eurocentric, colonial archive

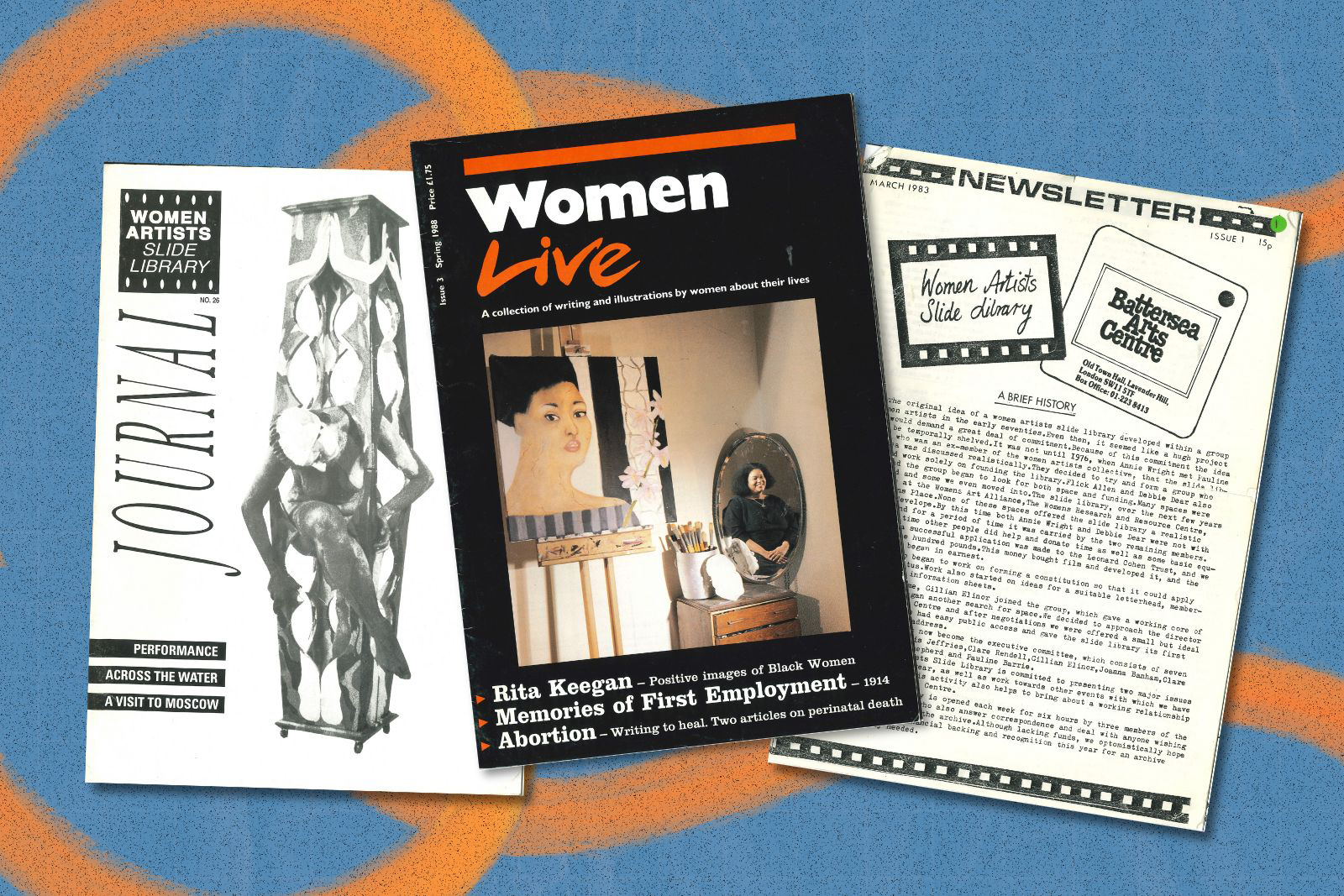

A handwritten label on a grey box reads “Touchy Feely”. It sits among several others in a room housing Goldsmiths University of London’s special collections and archives. The box’s items comprise materials from exhibitions, newspaper cuttings, leaflets, all belonging to the artist Rita Keegan, as part of her collection at the Women’s Art Library (WAL).

The label, according to WAL curator Dr Althea Greenan, simply describes items that offer an element of tactility: unique bits of ephemera that Keegan, the co-founder of the Brixton Arts Gallery and a prominent member of the Black Arts Movement, has collected over decades. “She kept everything around her because it was part of her practice and way of thinking,” Greenan says, referring to Keegan’s work as both artist and archivist, who drew on the medium of photocopying as a form of printmaking.

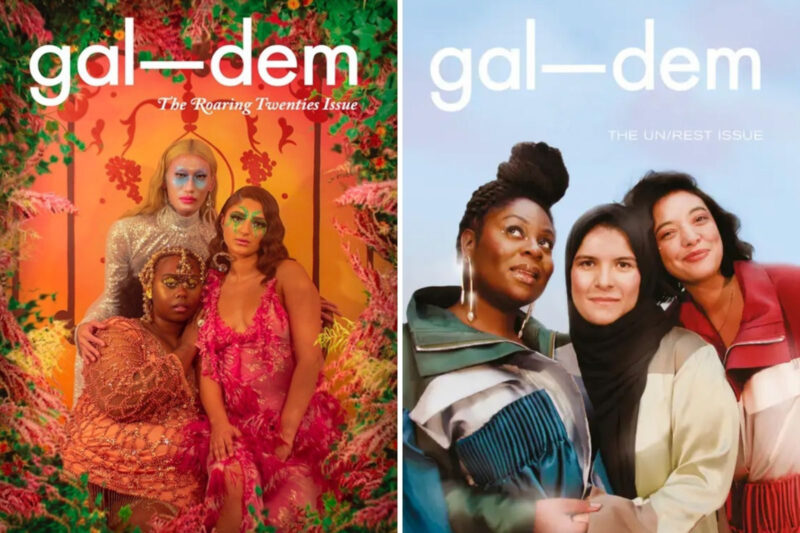

Keegan began cataloguing the work of women artists of colour, creating an index of profiles and exhibitions, reflecting a growing network of collective archiving practices led by minority communities in the 1980s, out of a need for spaces that truly represented their stories against an environment of discrimination. The “touchy feely” elements of her grey box hark back to this period. “It is the politics of visibility,” says Greenan.

Grassroots collective and community-owned archives like these are born out of a need to protect and mobilise histories that are at threat of being erased — or whose stories have been filtered through a Eurocentric, colonial lens. They emerge from an urgency and necessity to counter forgetting, according to the researcher Vasundhara Mathur. “When I think about collective archiving, I think about collective memory,” says Mathur, who curated a symposium exploring the future of community-owned archives, ‘The Archive is a Gathering Place’, at Tate Modern in May.

Mathur believes that collective archiving is not only about safeguarding collections of objects, but also preserving the networks and relationships that facilitated their creation. “There’s things we don’t document or we don’t have vestiges of, but we still remember,” Mathur says, referring to histories and memories that are passed down and transcend the paper practices of a traditional archive.

The symposium was inspired by Mathur’s research on the Japanese American civil rights activist Yuri Kochiyama, whose home in Harlem was a place where civil rights figures, Black Power activists, and members of the Asian American and anti-Vietnam War movements would coalesce. “In her living room, people were eating and talking and learning from one another, and helping each other survive and building up a sense of oppositional consciousness and solidarity in these relational, yet radical kinds of ways,” says Mathur. “That spirit of the archive really inspired this programme.”

The conference programme featured projects addressing archival silences within histories at risk of erasure, from the Palestinian Prisoners’ Movement, Urdu print culture, pan-African cinema to histories of indentureship in the Caribbean.

Connecting over their shared Jamaican heritage, Dr Tao Leigh Goffe, an interdisciplinary artist and professor at Hunter College in New York, and Dr Eddie Bruce-Jones, writer and professor at SOAS, began their project on colonialism and indentureship in 2022. They were driven by a concern over the physical disintegration of undigitized colonial records, as well as the absence of narratives surrounding the lived experiences of indentured labourers.

“It was immediately clear to us that we needed to have that juxtaposition between the official archive which is spoken in one voice, through the British colonial authority. And then we wanted to search sensorially, for how we could incorporate the voices of the actual people who were subjugated under these brutal institutions,” says Goffe.

Towards an Integrated Colonial Archive: Humanities, Law, and British Indentureship conceives an interactive digital space pairing archival documents related to the institution of indentureship in the Caribbean — ship logs, contracts, maps, court judgments — with oral histories, novels, music.

The design of the website hosting the archive, which will be launched in mid-2025, is inspired by a mangrove. “The mangrove is an ecological feature that exists in both the places that people left from, and the places they arrive,” Bruce-Jones says. It also evokes a spirit of rebellion and refuge — mangroves and coastal areas, Goffe says, were often used as hiding places from colonial authorities.

The website will be a digital space for users to access this history on their own terms. Clicking on a mangrove branch, for example, might lead to a recipe for curry appropriated and adapted by a British official, who, despite their absence in the official ledger, was likely watching a group of women from India produce the original recipes in a kitchen, Goffe says.

Efforts to archive more contemporary histories speak to similar impulses: the need to access and document community narratives from within. In 2017, Faisal Hussain, an artist and director of the heritage organisation TrueForm Projects, was alerted to the closure of Oriental Star Agencies, the Birmingham record store and label co-founded by Mohammed Ayub in 1970. It had served as a cultural touchstone among the South Asian diaspora in the UK, introducing audiences to bhangra and releasing the music of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan.

Hussain, who had grown up visiting the store with his grandfather, a neighbour and friend of Ayub’s, commandeered his family’s frozen food business van, recovering 3,000 vinyl records from the shop, where others had appeared to pick up bits of furniture to use in their artwork, or take records to resell. The process was slapdash and feverish, motivated by impending loss. “We had the limited resources of diaspora to save diaspora,” Hussain says.

Funded by a National Heritage Lottery grant, TrueForm is now archiving the collection — the largest of its kind in the UK — and Hussain plans to collect oral histories using the music as a catalyst for memories, as well as interpretations and reflections from artists and writers.

“We want to build our own library and museum, particularly because we think the nuances associated with it require it, which we don’t see in other museums,” he says. As part of a project documenting the history of South Asian youth culture, TrueForm collected several oral histories from Birmingham and beyond, spanning the period from the 1950s to the present day.

Heritage preservation, Hussain believes, requires detective work — following threads of information that someone might deliver, in order to fill in archival gaps in community histories. It also requires an engagement with diasporic trauma. “This work involves a lot of emotional toil, people breaking down through their telling of particularly traumatic history, of losing parents, of losing jobs, of racism,” Hussain says.

Bruce-Jones, as part of his and Goffe’s archival practice, likes to think of diasporas in the context of petrichor, the scent in the air after rain has fallen on dry soil. Water, like diaspora, is fluid, traversing borders. Petrichor is invisible and yet palpable, conjuring the sometimes inaccessible histories and ancestries that constitute diasporas. “We didn’t come from nowhere. But then connection is a really tenuous thing,” Bruce-Jones says. “There’s this ghostly quality that we can smell and can sense, but we don’t know exactly why.”

The practice of community-owned and collective archiving encapsulates precisely this. It is the inexplicable, the “touchy feely” of Keegan’s grey box, the invisible traces of a recipe’s original creator — what evokes memory beyond what is written or kept in the official register, which cannot always be quantified or enumerated — that requires preservation.

Newsletter

Newsletter