Ali Alzein Q&A: ‘Through beekeeping, I felt a feeling of peace that I hadn’t felt in so long’

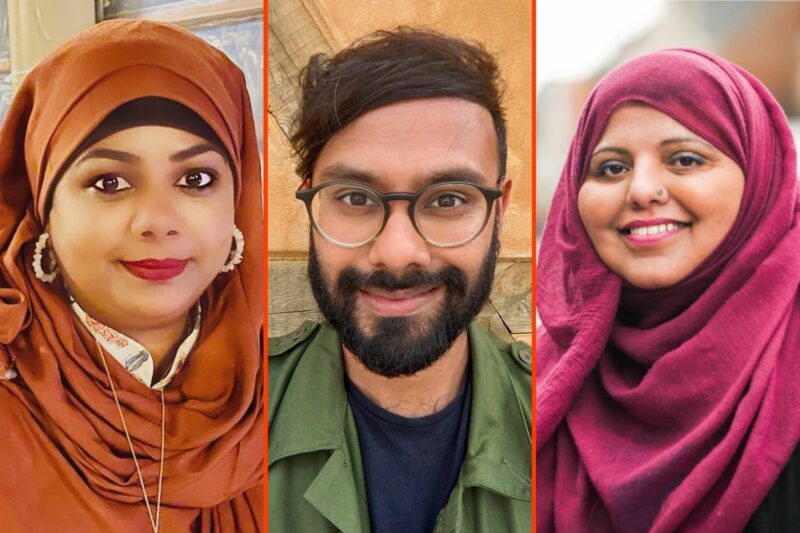

Ali Alzein, who settled in the UK after fleeing Syria’s civil war, uses beekeeping as a therapeutic tool for people seeking asylum. Photo courtesy of Bees and Refugees

The founder of Bees & Refugees on how a labour of love became a source of community

Ali Alzein, 39, fled his home in Damascus in 2014 after an escalation in Syria’s civil war. He sought asylum in London and soon after began working in Harrods. After gaining refugee status, he also began volunteering in Greece’s refugee camps. The disparity between the two worlds — that of Harrods’ uber-wealthy clientele and those languishing in displacement camps — became tough to witness.

In 2020, Alzein made a career change. He crowdfunded to set up Bees and Refugees, an environmental justice organisation that uses beekeeping as a therapeutic tool for people seeking asylum. Today, the volunteer-led group runs beekeeping, hive building and bee-related workshops in Hammersmith and Waterloo in London and Sevenoaks, Kent, where they opened a community farm and apiary last year.

So far, he has introduced 50 endangered black bee colonies across Greater London, and has helped run workshops for schools and community groups.

Alzein spoke to Hyphen about how ecological projects can help build bridges between communities.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Were nature and conservation a big part of your life back in Damascus?

Damascus is known for having a green belt around it, a forest that feeds the surrounding cities. The area is called al-Ghouta. In Arabic, it means a land filled with greenery and water. It’s like a little paradise. My grandfather and his sisters owned farms and land in this area. We used to spend every weekend there, where they had all kinds of animals, including bees. My fascination with nature started with my grandfather. He taught me the basics of farming, growing aubergines and courgettes, and looking after bees.

Why did you choose to pivot from high-end fashion to environmental justice?

Where I used to work, I was dealing with the 1% — people spending £500,000 on a dress or a bag. Before moving to the UK, I studied fashion design in Madrid and I love the creative side of it. But when I got into the consumer side of this industry, it was poisonous to my soul.

How did you start beekeeping?

I started keeping bees in London in 2019. It was just something that my grandfather suggested. I was telling him that I was really struggling, that I had been considering going back to Syria, even though my life would be in danger. So I introduced bees to my garden, and I converted a small garden apartment in Shepherd’s Bush to a little paradise — just 10 square metres.

The bees instantly filled the whole space with such magic. Their buzz grounded me, and I had a feeling of peace that I hadn’t felt in so long.

How do beekeeping and supporting refugees come together for you?

It was at the same time as the peak of aggression against refugees crossing into Europe. Even journalists were filmed attacking refugees who were trying to seek safety. I learned about native bees in the UK and how endangered they were because they were being exploited for their honey-making. And at the same time, refugees are facing incredible challenges and are being punished for seeking safety. That’s how I realised that these are two groups that would support each other and work together.

What’s been your experience in setting up the farm in Kent?

I don’t think many people in Otford village, where the farm is, had seen anyone in a hijab, or a Muslim person, pass by before. I’m white-passing, so I only get to witness racism when I speak, or when people ask me where I’m from or about my story, but walking around with my mum and sister, it’s been a lot more in my face.

Some people walked to the farm, saw that there were Muslims and they just walked right back outside. At least my neighbours have been much more friendly and open-minded.

I feel I need to do more to work with the local community and try to break these stereotypes in their heads.

What’s next for Bees and Refugees?

I want to make sure this project in Kent is fully sustainable. There are a few refugees who have been regularly volunteering and I hope to hire them as staff.

I would also like to take this model to other areas where refugees are really deprived of mental health support. I’m talking about refugees in the northern part of Syria, in Lebanon, in Turkey and Iraq. There are at least 14 million refugees who have been stuck in camps, with almost no access to the basics, so talking about mental health is a luxury there.

Newsletter

Newsletter