How hummus is helping plug the gaps in Italy’s asylum system

A diaspora Syrian living in Italy channelled the pain of seeing her country ravaged by civil war into a catering business that helps refugees build new lives

Joumana Farhoo mixes tahini and olive oil in a ceramic bowl, working expertly to create the smooth quality her hummus is known for, before blending it in with the chickpeas. For one of the five female chefs at HummusTown, a not-for-profit catering service that supports refugees in Rome, the process is second nature. Farhoo’s hands are busy, but her mind is elsewhere. “I’m sorry, I was travelling back in time and space,” she says, wiping away a tear. “You know, I would prepare this same dish for family gatherings back in Aleppo. Before the war, we were happy.”

Farhoo, 47, is one of 6.7 million Syrians who fled the country after 2011 when an attempt by a pro-democracy opposition to overthrow Bashar al-Assad, the Syrian president, erupted in civil war. The conflict raged for more than a decade, killing hundreds of thousands and displacing half the population. At least 6,000 Syrians sought asylum in Italy.

Farhoo found refuge in Rome in 2012 and employment as a housekeeper for Shaza Saker, a Syrian entrepreneur raised in Italy. Saker’s family moved from Damascus when she was three, when her father took a job advising on food and agricultural policies at the United Nations. When the civil war broke out, she — like most of Europe’s million-strong Syrian diaspora — watched on with anguished frustration.

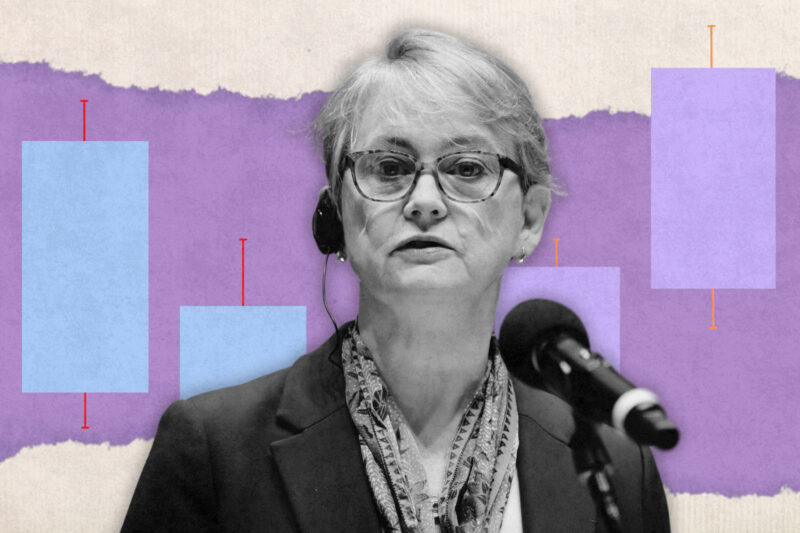

One night in 2013, Saker discovered Farhoo crying, distraught that she might never be able to return to Syria and worried for the safety of family and friends she had left behind, and felt compelled to do something tangible to help. “As a ‘luckier’ Syrian, I couldn’t just sit there and watch,” she said. “I think every diaspora child has a duty to pitch in when their people are in need.” As a food policy consultant like her father, her mind turned immediately to food.

Saker started hosting bi-monthly fundraising dinners at her house, charging €35 per person, gathering around a dozen people at a time, serving Syrian menus designed by Farhoo. She raised €5,000 in three months. Encouraged, she launched a crowdfunding campaign. Four years later, as the war raged on in Syria, she had raised €40,000, enough to rent a kitchen in Furio Camillo, a quiet, residential area of Rome. Here, in 2018, she opened HummusTown and hired Farhoo as a chef.

“We chose the name HummusTown because, among the many Syrian specialities, hummus is the most famous,” Saker explained. “And also because it’s Joumana’s — our first cook’s — favourite dish.”

Today, with a staff of 12 refugees, HummusTown runs a kiosk in Rome’s central Republic Square, a pop-up store at the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization headquarters and a catering service making Syrian food for private events in the capital. The reviews are good. “It’s really the first time I’ve eaten such good hummus,” one customer wrote on TripAdvisor. “I was served by a truly professional, kind and empathetic young Syrian woman. Only now did I discover that it is a non-profit project helping asylum seekers.”

Aside from offering employment, HummusTown also functions as a meeting spot and advice centre for Arab and Muslim immigrants in Rome, offering help to find work and assistance in negotiating the often complicated Italian employment bureaucracy. Saker is trying to help fill a gap she’s noticed in the Italian asylum system, which she believes doesn’t offer clear enough information on the support available to asylum seekers or sufficient help matching often highly qualified refugees with the right kind of employment.

Italy allows asylum seekers to start working 60 days after submitting an asylum application. In practice, however, many struggle for years to find a job appropriate to their skills. HummusTown’s graphic designer, Fadi Salem, 38, is a case in point. When he arrived in Italy from Syria at the start of Italy’s first Covid-19 lockdown in March 2020, he felt pushed by the asylum system to accept any job available to be classified as “employed”, which would mean he could officially be considered “integrated” and no longer require state support. But this wasn’t enough for Salem.

“It’s a matter of dignity, to find your place in a new country,” he said.

Salem met other Syrian migrants at government offices filling out paperwork and asked them for advice. They directed him to HummusTown and, four years later, he is an integral part of Saker’s team, designing the menu and flyers for events.

“Only a fellow Syrian immigrant with decades of experience living in Italy could truly have understood my needs and shown me how to operate here,” Salem said. “At HummusTown I found the type of support I struggled to find elsewhere.”

Farhoo, too, says that HummusTown helped her to better integrate with a new community. “Shaza’s project has been a life-changing opportunity for me. It has given me a new purpose: to share something positive from my culture with my new country,” she said.

Saker is now looking to expand her organisation. HummusTown recently partnered with an Italian restaurant on the outskirts of the capital which gives its kitchen over to a HummusTown chef once a week and shares the profits of their service. Sakar is also working to extend the organisation’s support to other vulnerable refugee communities as well as economically marginalised Italians.

“Opening this space has made me realise the challenges that refugees face nowadays while trying to integrate in Europe,” Saker said. “They clearly need better support from competent authorities, but it’s important that people of their own diasporas also guide them in that process.”

Newsletter

Newsletter