Has Labour thrown away Britain’s most marginal seat?

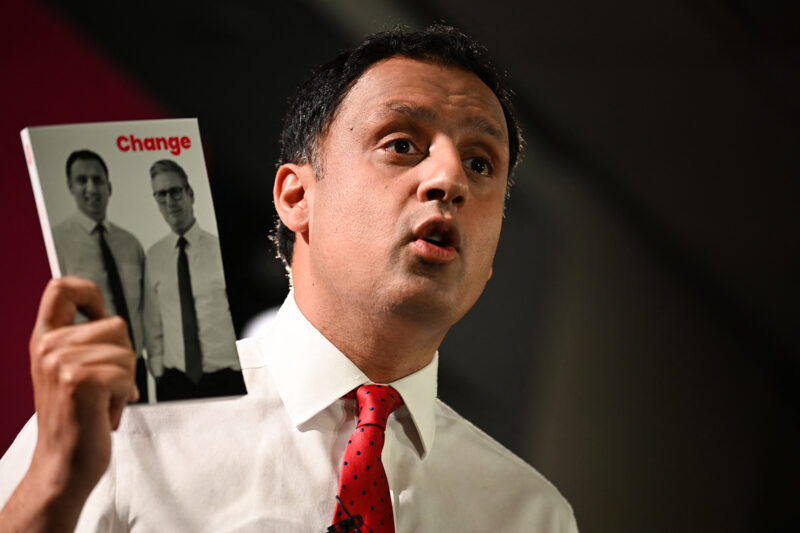

A few months ago, Burnley seemed like a shoo-in for Keir Starmer’s party. But Labour’s position on Gaza cost it control of the local council — and now it has a fight on its hands

Burnley was, on paper, ready for change. After the shock election of its first Tory MP for a century in the 2019 general election, this deindustrialised northern town was squarely back in Keir Starmer’s sights.

The seat was being touted as Labour’s easiest win, with new boundaries meaning the party needed barely 100 extra votes to snatch the seat back from Antony Higginbotham. But in November 2023, Burnley’s political landscape shifted dramatically — and not in Starmer’s favour.

Half its Labour councillors — including council leader Afrasiab Anwar, and all those who were Muslim — quit to go independent. Thanks to a deal with the Greens and Liberal Democrats, the independents kept control of the town hall, and Labour was relegated to the opposition benches.

The reason? Gaza — or, more specifically, the position Starmer and his shadow cabinet colleagues had taken on Israel’s bombardment of the Palestinian people, and the zero-tolerance approach his party adopted in relation to any criticism of Israeli actions.

The defections represented the collapse of a month of emergency diplomacy. Anwar had spent most of October, following the Hamas attacks on Israel and the commencement of Israel’s siege and bombardment of Gaza, trying to find a compromise behind the scenes that would keep the party together.

Officials at Labour HQ, recognising how many Muslim councillors were unhappy about Starmer’s stance on Gaza, had organised a series of Zoom consultations between Labour bigwigs and local leaders such as Anwar, in the hope of defusing the situation.

When we spoke in November, Anwar told me how he had spent the meetings trying to persuade senior party figures such as Angela Rayner, David Lammy and Yvette Cooper to balance their statements supporting “Israel’s right to defend itself” with condemnation of the Israel Defense Forces’ attacks on civilians — and a contextual recognition of the violence and oppression to which Palestinians had long been subjected.

Initially, he hoped that discussing these issues in private, without voicing any public criticism of Starmer, might lead to a significant shift of tone and changes in policy. But within a few weeks, that optimism was gone.

Anwar felt he’d simply been taking part in what he called “tick-box exercises”. Labour’s leaders, he told me, weren’t genuinely open to reconsidering their position, or prepared to speak out in line with the anguish and distress that their many loyal Muslim voters felt in response to the death and suffering being visited upon Gaza City, Khan Yunis and Rafah.

He also recognised that he was himself becoming the focus of community frustration, and that fellow Muslims who knew him were looking to him for leadership. He explained to me that, when he attended part of a long-scheduled Islamic conference in Burnley in late October, scholars advised him to reflect on whether he was acting and speaking in line with his beliefs. Young people, in particular, urged him to speak out in line with what they knew were his true values.

More generally, in constituencies across Lancashire and West Yorkshire, Muslim party activists were growing frustrated by what they saw as the “double standards” shaping Labour’s wider positions. At meetings held in activists’ houses in Burnley during late October, concern was voiced about the discrepancy between how the party had mounted immediate and unambiguous opposition to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, yet there had been years of foot-dragging and dissimulation over the Indian government’s repressive actions in Kashmir, with Starmer now taking a “hands-off” position and defining it as “a bilateral matter between India and Pakistan”.

And so the local party split. Anwar publicly called on Starmer to back a ceasefire in Gaza or resign on 3 November 2023; days later, he and 10 other councillors quit Labour.

Politicians who cross the floor, or go independent, are often punished at the ballot box. But in Burnley, Anwar and his colleagues have retained public support: all but one successfully defended their seats in the May 2024 local elections, and Anwar himself remains leader of the council. What this all means for the general election on 4 July is far from clear. Local and national politics are very different beasts, and one recent YouGov poll for Sky News predicts a “safe Labour gain” in the seat. But such polls, as Guardian columnist John Harris has pointed out, often fail to capture the dynamics of individual races.

In theory, Labour only needs a 0.13% swing from the Conservatives in Burnley to win back the seat it lost to Higginbotham, one of Boris Johnson’s “Get Brexit Done” Conservatives, in 2019.

One reason Labour was meant to have such a good chance of winning Burnley back was a recent change to the constituency boundaries that added two wards from the neighbouring borough of Pendle. These areas, in and around Brierfield, are home to many Pakistani-heritage Muslims. Labour began courting the pioneer immigrants who came to work in the now-closed cotton mills in the late 1960s, and they and their families have traditionally voted for the party since.

I lived and worked in Burnley for many years, and I have revisited the town regularly in the last few months. As recently as September, there was a sense of inevitability that Labour would win back the seat whenever Rishi Sunak chose to go to the country. Byelection victories and defections from other parties had edged Labour to within one seat of having overall control of the council. There was a sense of unity and shared purpose among party activists. Anwar, then still leader of the governing Labour group, had built a well-deserved reputation for competence and for reaching out to communities across the borough.

Another positive was that Anwar’s group was diverse: of 22 Labour councillors, 10 were Muslims of Pakistani or Bangladeshi heritage, including four women. The make-up of Burnley’s biggest political party showed how far things had moved on from 20 years ago, when — as I outlined in my book, On the Burnley Road: Class, Race and Politics in a Northern English Town — the far-right British National party was stirring up racism and division in the town, and winning council seats as a result.

What has happened in the months since October is, of course, part of a wider national picture. Many long-serving and committed Labour people have felt little choice but to leave a party now led by a man who defended Israel’s “right” to withhold power and water from citizens in Gaza.

Alongside the many councillors and activists who chose to quit, other dedicated members have been squeezed out or excluded. Next door to Burnley, in Pendle, 20 Labour councillors resigned in April, claiming their local party was being “bullied” in relation to concerns members had on Gaza. In Walsall, Leicester, Blackburn and many other places, as well as in the case of Faiza Shaheen being dropped as a parliamentary candidate in Chingford and Woodford Green, the constraints being used to reassure business donors and potential centre-right voters that Labour is under control are narrowing the party’s social base and culture.

Long-serving activists in Burnley who left Labour at the same time as Anwar have told me their former party will no longer be able to draw on the diverse views, experience and wisdom of thousands of former supporters, including many who are racialised and have experienced discrimination and Islamophobia.

This large-scale loss of support from Muslim political activists risks the hoped-for majority Labour is chasing in Burnley and towns with similar proportions of Muslim voters. Starmer’s Burnley candidate, Oliver Ryan, can now no longer count on the vote — or door-knocking efforts — of thousands of Muslim people who have previously cast their ballots for Labour. The anticipated boost in Muslim votes from Brierfield cannot be relied on, either. The councillors there are all now independent, having left Labour in developments linked to the Gaza conflict.

Instead, the Liberal Democrats — who came a distant third in 2019 with 9% of the ballot — are hoping many Muslims will get behind their man, Gordon Birtwistle.

The Muslim Vote website identifies Birtwistle, 80, as the “community-endorsed” candidate, and he claims that on Eid-al-Adha there were calls at “every Mosque in the constituency” for Muslims to vote for him. Such calls are consistent with the feelings of those activists who left Labour in November. One told me that “we need to follow through on what we stand for … we’ve got to let Labour know that Muslim voters are not a pushover”. This sentiment is confirmed by Burnley council leader Anwar, who told the Guardian that former Labour activists and voters have long “been taken for granted within the party … and that’s completely immoral”.

However, Birtwistle is not wholly correct in his assertion that “the councillors that went independent — they’re on the streets helping me”. Nor are community leaders actually able to deploy the votes of thousands of people as a bloc. My sense is that the power of the UK’s “biraderi” community networks — where powerful male figures were able to dictate how large numbers of British Pakistanis and Bangladeshis should vote based on clan loyalties — is nowhere near what it once was. The people who actually influence opinion among Muslim voters today are increasingly likely to be young professionals and to include a good proportion of female voices.

Although the majority of Burnley’s former Labour Muslim councillors are encouraging a vote for the Lib Dems, this is happening in a relatively low-key way. What’s more, a small number of the councillors who went independent are — without explicitly endorsing Ryan — beginning to make the argument that Muslim people need a voice when Labour comes to power nationally. That means, they say, that Muslims need to be represented within the party, and to be recognised as having lent Labour support in the general election.

This was certainly Tulip Siddiq’s pitch when she was in Burnley campaigning for Labour on 20 June, taking time off from doorknocking in Hampstead, where she’s been the party’s MP since 2015. Siddiq is related to Bangladesh’s prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, and made a particular effort to connect with potential Labour voters among Burnley’s Bangladeshi-heritage residents. It is also the position of Wajid Khan, the only local prominent Pakistani heritage politician who — quietly — stayed loyal to Labour at the time of November’s defections. Lord Khan, a former mayor of Burnley and MEP, is now a Labour peer.

Such efforts are beginning to have an effect. Some Labour supporters I have spoken to — including Muslims — observe that the 300 “community leaders” who granted Birtwistle his “endorsed” status at a closed-door meeting on 6 June “must have short memories”. When he had a short stint as Burnley’s MP during David Cameron’s premiership from 2010, Birtwistle was part of the Treasury team behind the austerity programme that hit local services and axed urban regeneration funding for Burnley and Pendle, including areas where most Muslim voters live. The multi-million pound Elevate scheme to renovate thousands of Victorian terraced houses was summarily ended, and support for locally popular programmes such as Sure Start drastically reduced.

The range of different views now surfacing in the community are confirmation that Muslim voters cannot be seen as a homogenous bloc that can be handed in its entirety from Labour to the Lib Dems or whoever. As Taj Ali has argued for Hyphen, such concepts hide the reality of people’s actual lives and views.

Labour’s current efforts to reconnect to Muslim voters, as illustrated by Siddiq’s visit, have by no means been wholly successful. But they indicate a much more positive attitude than the concerning views I heard directly from a couple of white men backing Labour when I was in Burnley a couple of months ago. They argued then that Labour’s prospects looked so strong that they were likely to win — in Burnley, as in the country overall — “whether or not Muslims vote for us”.

This was a negative vision of winning that highlights the rift between Labour and many thousands of people who have long identified with the party, at the same time as suggesting that this broken relationship does not matter. The notion that the change Starmer says he wants to achieve can come about without engaging support from Muslim people would not bode well for future politics.

However the votes are cast on 4 July, the resilience and development of democracy in the UK depends on political parties learning to engage with the varied concerns, insights and hopes of people from all the communities they wish to represent. That means involving them — not squeezing them out or shutting them up when they express a view that’s not in line with a party leader’s current view.

As part of this, the potential influence and impact of the growing number of voters who are Muslim — alongside other aspects of their identities as women and men, workers and business owners, daughters and mothers, fathers and sons, members of different generations and so much else besides — will surely be felt in varied and diverse ways, and not determined by “community leaders” deciding “what everybody thinks”.

Newsletter

Newsletter