The British Raj-era poet who returned a knighthood

The writings of the Bengali Nobel prize-winning author Rabindranath Tagore continue to resonate with young British Muslims to this day

–

Growing up in Rochester in the 1970s, my immigrant parents tried to instil in me their love for Bengali literature. But as the only family of colour on the street we lived on, I was acutely aware that I looked different to my white classmates. At school, I never saw anyone who resembled me in the books we read — my closest encounter with a person of colour occurred when I read Pocahontas.

I was first introduced to Rabindranath Tagore’s writings at the age of 10, when my uncle phoned from Sylhet to update my father on the increasingly hostile situation in Bangladesh. I could hear people chanting in the background. It was 1981 and the year Ziaur Rahman, the 7th president of Bangladesh, was assassinated in a coup d’etat by officers in the Bangladesh Army.

The crowds were chanting the national anthem of Bangladesh, written by Tagore. “Amar shonar Bangla, ami tomay bhalobashi,” (My golden Bengal, thee I love). His poetry was a moving reminder to my parents of the relatives who had lost their lives during the bloody war of independence from Pakistan in 1971.

As a child living in a predominately white town, I often felt uncomfortable speaking in Bengali, having been conditioned to think that only the English language was valued. Later when I moved to Tower Hamlets in the early 1990s, I attended a celebration of Tagore’s work at the Brady Centre. I heard how he wrote about the revival of the eastern bloc of countries in Asia, like Bangladesh, and how it challenged Western supremacy. I also heard about how his writings called for a future beyond nationalism, based on racial tolerance.

Tagore helped me realise that to be bilingual in Bengali and English was a gift and not a burden

Since then, Tagore’s writings have helped me understand how class and colonialism once thrived under the British Raj. They also gave me an understanding of the British Raj that was not taught to me at school.

The first non-European to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913, Tagore was born in Calcutta to a middle-class, Bengali Hindu (Brahmin) family in 1861. He was educated in England and first began writing poetry at the age of eight; he was a published poet at the age of 16. Tagore eventually dropped out of a law degree at University College London, to dedicate his time studying Shakespeare, along with English, Scottish and Irish literature and music.

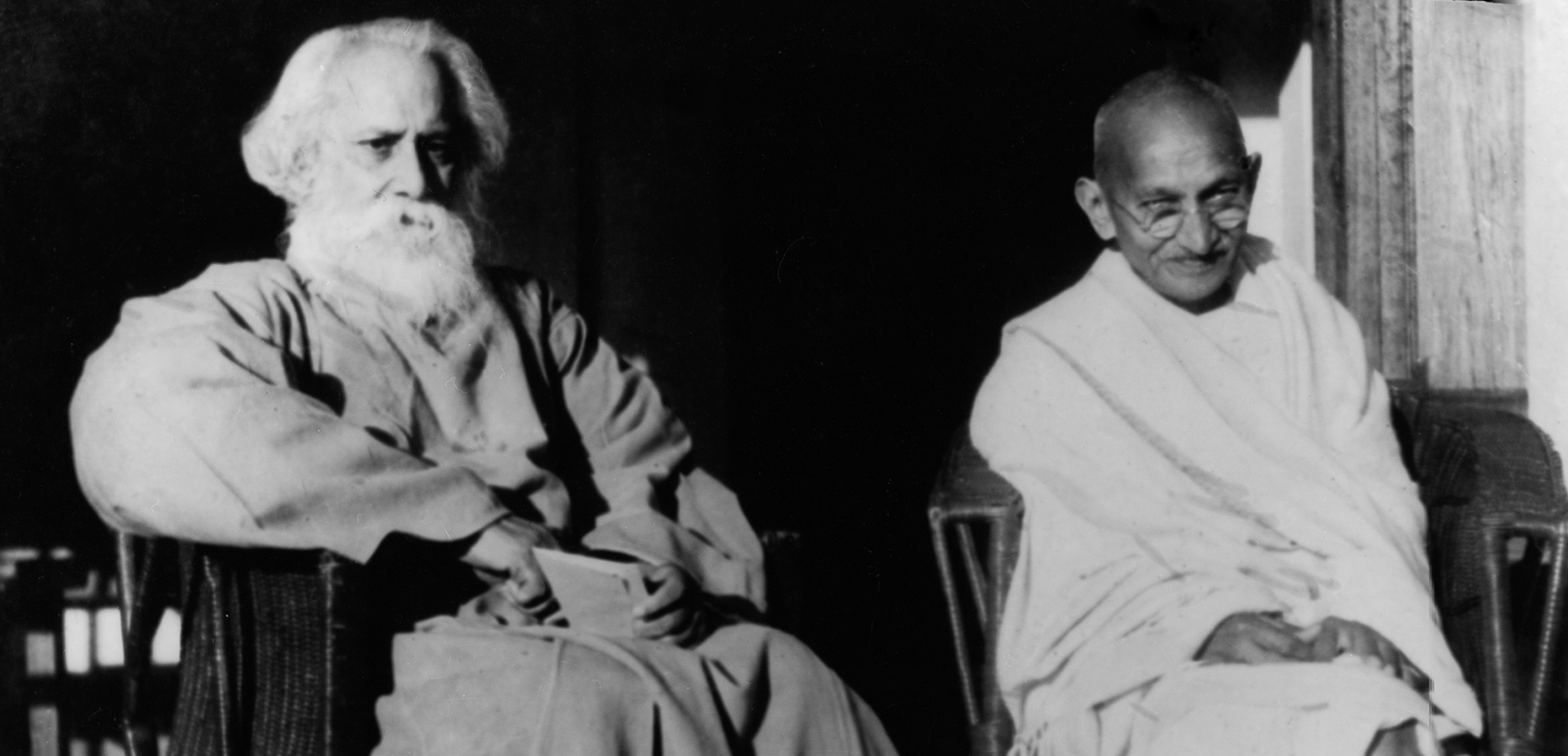

He returned to India in 1883 and established his own school and continued to publish poems, stories and novels. His writing incorporated a number of themes, questioning the role of caste in India’s social hierarchy in his poem The Sacred Touch (1913). Like Gandhi, with whom he enjoyed a friendship until his death in 1941, Tagore shunned the Hindu caste system of untouchability, writing about it in his drama Chandalika (1938). His work also resonated deeply with many Muslim citizens of Bengal and Bangladesh who agreed with his core themes of humanism and nationalism.

Tagore received a knighthood in 1915, but returned the title in 1919 in protest against that year’s massacre at Jallianwala Bagh, also known as the Amritsar massacre, which resulted in the death of 379 Indian civilians at the hands of British forces. While he was the first recipient to ever return a knighthood, the British refused to accept his resignation, afraid that his gesture would undermine their authority. He would continue to be addressed as “Sir Rabindranath” until his death in 1941.

Tagore’s letter returning his knighthood was printed in several newspapers, thrusting him into India’s ongoing struggle for independence. Published in the Times of India his letter highlighted the injustices and punishments inflicted upon ordinary Indians at the hands of the British: “Considering that such treatment has been meted out to a population, disarmed and resourceless, by a power that has the most terribly efficient organisation for destruction of human lives, we must strongly assert that it can claim no political expediency, far less moral justification.”

Decades after his death, his writings would continue to influence my immediate family in Bangladesh. My mother’s cousins were freedom fighters in the 1971 conflict between East and West Pakistan that lasted nine months and culminated in an independent Bangladesh. Tagore’s poem Heaven of Freedom resonated with them because it expressed their deep desire for an independent homeland: “Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high; Where knowledge is free; Where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls; Where words come out from the depth of truth.”

People in the Indian subcontinent were not the only ones touched by Tagore’s works, which have been widely translated into over a dozen languages. The Irish poet and playwright WB Yeats, referred to his writings as full of “untranslatable delicacies of colour”. In St Stephen’s Green in Dublin, known for the failed 1916 Easter Rising, stands a bust of Tagore, the Bard of Bengal, amongst other historic sculptures.

He is still celebrated across the world today. A two-day festival of Tagore’s works was held in May at Rich Mix in east London, which included renditions of his songs performed by the renowned Bangladeshi singer, Rezwana Chowdhury Bannya.

After over four decades of living in Britain, I see generations of people from the Indian subcontinent overcoming racial adversity to become an integral part of British society. Their experiences speak to something Tagore once wrote: “You can’t cross the sea merely by standing and staring at the water.”

Newsletter

Newsletter