Social media influencers have no right to declare anyone an apostate

Muslim organisations need to challenge online firebrands and provide better examples for young people

–

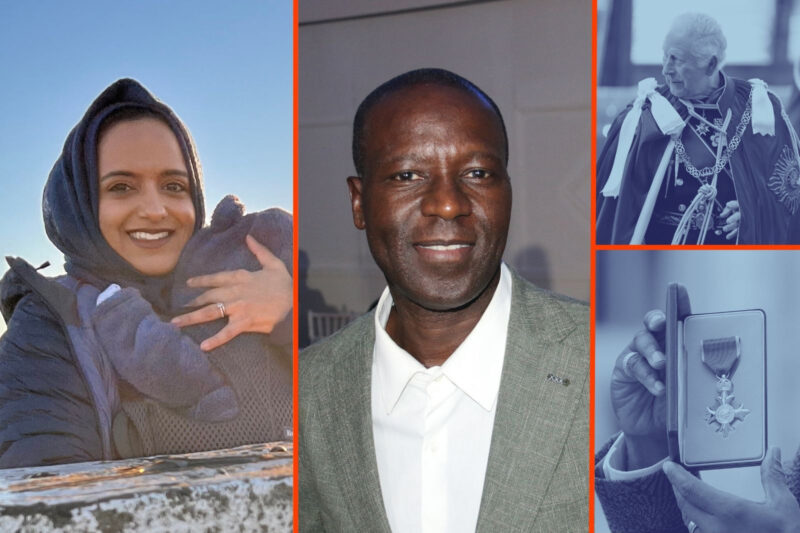

A few hours after Humza Yousaf was sworn in as First Minister of Scotland on 29 March — the first Muslim to hold the office — Mohammed Hijab took to YouTube to excommunicate him from the faith.

Hijab, a well-known British Muslim influencer who has earned an online reputation for his provocative, sometimes aggressive debating style, said his judgment was based on Yousaf’s earlier statements on homosexuality and same-sex marriage.

The social media fallout that resulted illustrates how conversations about social and political issues — particularly those carried out online — within Muslim communities are being hijacked by a small number of online religious personalities. Responsible for an endless stream of content, this small group of influencers has incentivised intra-Muslim confrontation and cancel culture, while obfuscating important debates with disinformation.

Recordings of debates from Speakers’ Corner, lectures and reaction videos — many of which accumulate hundreds of thousands of views — are having a counterproductive effect on how people understand Islam, with millennials and members of Generation Z in particular being drawn into the dubious agendas of individuals competing for followers and financial gain.

Videos that attract the most attention include heated arguments on Christian-Muslim relations, “traditional” masculinity and responses to other, rival influencers. You only have to watch a few to recognise their aggressive, confrontational style and the insular version of religious identity they promote, hostile to all ideological opponents — a broad group that frequently includes liberal Muslims, atheists and feminists.

This generation of online activists has risen to prominence over the past decade thanks to a large volume of clickbait content. Some of the videos aimed at young Muslim people struggling with their faith could be seen as beneficial. However, it doesn’t take long to find other pieces of content in which the makers offer sweeping pronouncements on a range of subjects far beyond their remit, including apostasy, complex points of Islamic law and theology.

Influencers such as Daniel Haqiqatjou, “Dawah Man”, “Ali Dawah” and Mohammed Hijab are all part of a cluster of English-speaking YouTubers known as the Muslim Manosphere. Their style of digital dawah (invitation to Islam) was developed in the late 1990s and early 2000s by the likes of Abu Hamza, Omar Bakri and Anjem Choudary — radical preachers who gained notoriety for their inflammatory rhetoric. The nature of social media means that this style of dawah is far less about inviting people to Islam and more about showing the purported superiority of a certain strand of conservative Islam and shaping the thinking and behaviour of already religiously inclined young people.

‘The content of many Muslim YouTubers perpetuates the narcissistic, reactionary celebrity culture that Islamic values are supposed to stand against’

Hijab, who has already been involved in a number of controversies, is noted for his numerous online altercations with other Muslims. He does not appear to have taken the advice of one of his teachers, the well-known scholar Shaykh Haitham al-Haddad, who wrote a balanced evaluation of Yousaf’s election as leader of the Scottish National Party.

Declaring an individual to be a disbeliever is a serious matter, according to Dr Usaama al-Azami, lecturer of contemporary Islamic Studies at the University of Oxford. “Theologians make a distinction between saying that a statement is disbelief (kufr) and saying that the individual making the statement is a disbeliever (kafir),” he says. “Declaring him a disbeliever is not theologically reasonable.”

Azami goes on to add that, beyond their inherent theological problems, such declarations can have devastating impacts in the real world. “It is a problem when certain individuals recklessly declare people to be apostates in a country in which vigilantism on such matters has had deadly results in recent years,” he says, referring to the sectarian murder of Asad Shah in Glasgow by Tanvir Ahmad in 2016.

Dr Khadijah Elshayyal, a research fellow on the Digital Islam in Britain project, says these kinds of incidents are likely to become more regular as people seek to imitate the styles of well-known religious influencers:

“This incident highlights ongoing concerning patterns relating to a confluence or a blurring between those playing an influencer role and those offering religious guidance. In this sense, many digital spaces, and social media in particular, incentivise drama and controversy,” she says.

In that light, the Hijab-Yousaf debacle represents a significant and worrying shift in the way public dawah is conducted. The growing popularity of influencers such as Hijab is likely to inspire copycat condemnations of people summarily judged not to be “authentic” Muslims — in almost every case individuals with far less protection than an elected head of state. If those ideas continue to spread, they will make the online and offline spaces in which young Muslims need to talk about their religious identities increasingly polarised and unsafe.

Ironically, the content of many Muslim YouTubers perpetuates the narcissistic, reactionary celebrity culture that Islamic values are supposed to stand against. Sensationalised titles and salacious content have become the norm for a growing number of Muslim influencers competing for attention from an audience with what appears to be an increasingly short attention span.

The problematic nature of this space has been amply demonstrated in the reactions to the reported conversion to Islam of Andrew Tate, perhaps the most controversial of all male online personalities. Tate was attracting young Muslim males to his videos even before his apparent embracing of the faith and has since made a number of religiously objectionable statements, including claiming to be a god. Hijab and others went out of their way to defend him and offered excuses for his comments in a way not afforded to Yousaf.

This hazardous course can be corrected if more recognised scholars and mature voices engage with the many Muslims seeking online guidance and inspiration. This requires qualified religious individuals to challenge compulsive attention seekers by providing equally compelling content that sets better examples. More importantly, Muslim community institutions must step up, address difficult issues and reach impressionable young people who are too often being manipulated and exploited by far less scrupulous voices.

Newsletter

Newsletter