Humza Yousaf: ‘Scotland has been radical, bold and will be independent’

As the race for the leadership of the Scottish National Party — and to become the nation’s first minister — draws to a close, the Glasgow MSP talks about his hopes for the future

–

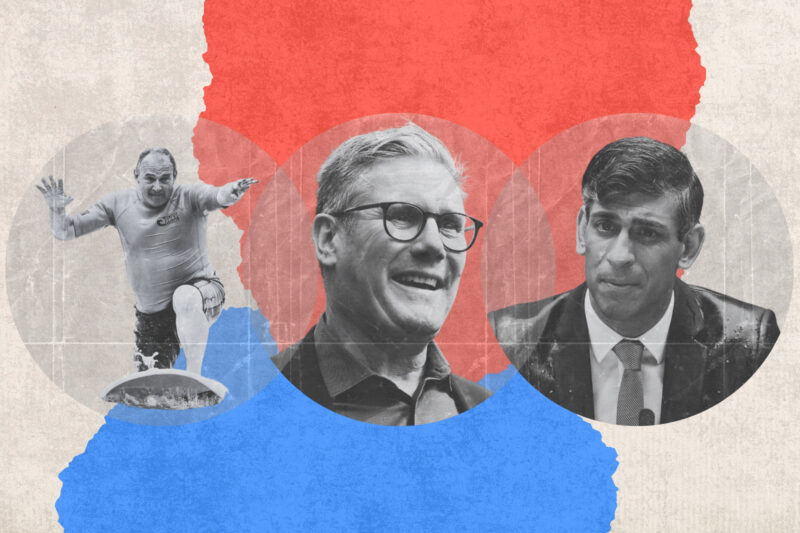

There is snow in the early March air as the stuttering Ford Focus containing Humza Yousaf pulls into a council car park in Lanark, a small market town half an hour down the motorway from Glasgow.

A modest press group has been huddled outside a local housing association in the chill for half an hour, waiting impatiently for the man many expect to be the new first minister of Scotland.

Barely a week into the official campaign to become leader of both the Scottish National Party and the nation it governs, Yousaf has crisscrossed the country to drum up support from party members and, perhaps more importantly, the voters he needs to convince in the long term.

The departing first minister, Nicola Sturgeon, could barely walk down the street without being mobbed, but Yousaf has work to do before he hits the same height of public recognition.

“Sorry about the snappers, they always catch you from your worst angle,” he laughs as he makes small talk with the housing association workers who have downed tools for an organised photo opportunity.

The meet and greet in working-class Scotland is an art perfected by Sturgeon that Yousaf – or Humza, as he is almost universally known — is still mastering. The 37-year old Glasgow-born politician was always tipped for the top within the SNP, but it was only the surprise resignation of Sturgeon as first minister and leader of the party in February that thrust him into the national limelight.

Within hours of Sturgeon’s announcement Yousaf emerged as the bookies’ favourite, a polished political operator with a decade of experience in parliament, who vowed to continue his predecessor’s legacy of broad consensus politics and progressive internationalism.

“I hope it continues to be a progressive country, a country that is socially just, that puts the needs of the most vulnerable at the forefront.” Yousaf says when I ask about his long-term vision for Scotland. “It’s a country that has been radical and bold, and most importantly, it’s a country that will be independent.”

It is an ambitious pitch. Should he win the leadership race, the pressure will be on to succeed where his predecessors have failed and deliver a winning coalition for independence.

Yousaf’s ascent to the highest office in the land, with Sturgeon’s blessing, now seems an obvious trajectory, but it was not inevitable. When he was a rookie activist, back in 2007, the SNP still played second fiddle to the Scottish Labour Party and the idea of independence was widely viewed as a distraction from the country’s real issues.

An ambitious young politician wanting a fast track into parliament would have been far better off pinning on a red rosette rather than the SNP’s deep yellow. Even after the SNP formed a weak minority government in 2007, Labour and the Liberal Democrats were a safer bet for anyone seeking to enter the corridors of power.

‘I’m proud to be a Muslim. I’ve never shied away from it, but my faith is not the basis by which I legislate’

Humza Yousaf

Born into a middle-class Scottish Pakistani family on Glasgow’s southside, Yousaf took a familiar path from the fee-paying Hutchesons’ Grammar School to the University of Glasgow to study politics. A rapid rise through the party machine as a staffer in the Scottish Parliament followed.

Yousaf’s big breakthrough dovetailed perfectly with the seismic shifts from the Labour Party to the SNP that have transformed Scottish politics in the past 15 years. In 2011 the SNP stormed to a previously unthinkable full majority of seats, capitalising on apathy towards Labour and unease about the return of the Conservatives to power in London.

Yousaf’s main rival for the post of first minister is Kate Forbes, an evangelical Christian and member of the conservative, Protestant Free Church of Scotland. Forbes rose up the ranks of the party in much the same way as Yousaf, but represents a more traditional wing of the SNP which believes that the party has veered too far left, both economically and socially.

Forbes’s views on equal marriage, abortion, transgender rights and having children out of wedlock jar with the self-image of a nation that has developed a reputation as socially and economically progressive. Both she and Yousaf have faced questions on how faith informs their politics, but whereas Forbes openly admits to being guided by her beliefs, Yousaf views his as part of the diversity of the country itself.

“I don’t think it is about the beliefs, I think it is about whether or not you allow those beliefs to interfere in the legislative process,” he says. “I’m proud to be a Muslim. I’ve never shied away from it, but my faith is not the basis by which I legislate. I understand my responsibility to legislate in the best interests of everybody in the country.”

Yousaf’s careful balance of faith and politics was already evident as a student in Glasgow. Alongside his activism in the SNP’s youth wing, he chaired the University Islamic Society.

They may differ in political and religious beliefs, but Yousaf and Forbes are both products of a new political class that emerged in Scotland after it regained its parliament in 1999. True believers in the cause of independence, with an ability to say the right things to the right people and the political instincts to navigate the party machine, both found themselves sponsored by different wings of the SNP’s big tent. The problem for Yousaf is that coming of age in the good times may not have prepared him for the tough years ahead.

“Talk to an older generation of SNP activists about their experience of Scottish politics, and they’ll tell you a story of political endurance and failure,” says Andrew Tickell, a constitutional lawyer and newspaper columnist who has built a reputation as one of the independence movement’s most self-critical voices.

“Both of the frontrunners’ formative experience of party politics has involved riding the crest of a wave they did not create and it is not quite clear, having learnt the habits of victory, whether either of them are intellectually or emotionally prepared for the challenges awaiting them and the party.”

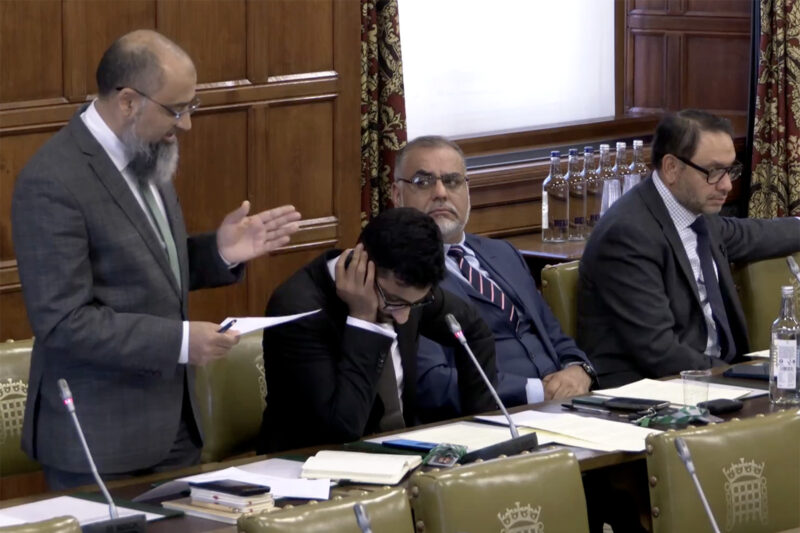

As that wave gained momentum in the late 2010s, Yousaf began working as a researcher for Glasgow MSP Bashir Ahmad, the first non-white and Muslim member of the Scottish Parliament. When Ahmad died from a heart attack just two years into his term, Yousaf was the obvious candidate to continue the party’s presence in the city’s Pakistani community and build on the support for the SNP cause that Ahmad had secured.

Yousaf has often cited Ahmad’s summary of the SNP’s inclusive civic nationalism as being not about “where we come from, but where we are going together, as a nation”.

That approach to Scottish identity was what allowed the SNP to bring on board a variety of groups who might naturally be suspicious of nationalist politics, from the Catholic left to free-thinking Highlanders and the nation’s Glasgow-centred South Asian population.

Traditionally, Pakistani and Indian minorities had drifted towards Labour. The current Scottish Labour leader, Anas Sarwar, is the son of Mohammad Sarwar, Britain’s first Muslim MP. If Yousaf becomes leader of the SNP, two of the big three parties of Scottish politics will be led by men from the same Glasgow community. They even went to the same school at the same time.

“It is great that a Scottish-Pakistani Muslim can make it to the top of the SNP and be first minister,” says Peter Hopkins, a professor of social geography at Newcastle University who led one of the first in-depth studies of Scottish Muslims and their political views.

“Certain people from the Muslim community can succeed,” he says of Yousaf and Sarwar’s prominence. “These men are set to be the two most senior politicians in Scotland, so there’s definitely something to be said for that. But Islamophobia is still seen as a marginal issue by Scottish politics more generally.”

This is backed up by the research Hopkins and his colleagues undertook, speaking to Scottish Muslims about what politics meant to them.

“There are Muslims who are very engaged and very active and want to go to parliament, who vote and engage in politics,” says Hopkins. “There are also Muslims who felt the political system as a whole had stigmatised them and that if they got involved, they risked being categorised as ‘radicals’.”

This is where Yousaf must walk a fine line: one foot in the Glasgow community he comes from and the other firmly in the political mainstream. Yousaf’s faith has always been a big part of his personal motivations and in a nation where the SNP has as many members as the entire Muslim population, he believes his achievements so far, as the non-white son of immigrant parents, point to important changes in what it means to be Scottish.

“I think it means a lot,” he explains, as his press officers usher him inside, ready for his next meeting. “It doesn’t matter what your background is, what your faith is, what your race is. There is no barrier to being in contention for the top job.”

Like his mentor Nicola Sturgeon, Yousaf faces an arduous and possibly unachievable task in leading the SNP and the broader independence movement to its promised land. His most vital job, however, may be making the new multicultural and classless Scotland that he believes in a reality.

Newsletter

Newsletter