‘Muslims have a 100-year architectural history in Britain’: Shahed Saleem Q&A

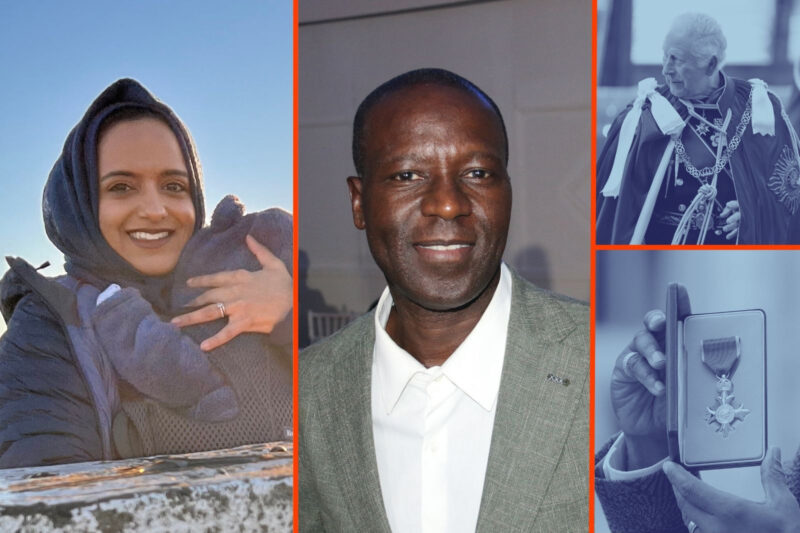

Photograph courtesy of Shahed Saleem/Rehan Jamil

The architect, artist and designer of the V&A Ramadan Pavilion talks about the unique style of the British mosque and if we’ll soon be praying in the Metaverse

–

Shahed Saleem is a UK-based architect, artist and design studio leader at the University of Westminster School of Architecture. His work focuses on the building styles of post-migrant communities and their relationships to nationhood, heritage and religious identity. Starting out as an architect in the 2000s, Saleem has spent years studying mosques across the UK. That research led to a book, The British Mosque: An Architectural and Social History, published in 2018. In 2021, he was invited to co-curate the V&A’s contribution to the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale, comprising three life-size installations of British mosques.

Saleem, an award-winning architect and artist, was commissioned to design the Ramadan Pavilion, presented on the concourse of the Victoria & Albert Museum — an immersive installation that celebrates “the lived experiences of Muslims across the UK and globe during the holiest month of the Islamic calendar”. Incorporating British and Islamic architectural references and motifs, the structure aims to present the mosque as an open, inviting space, while challenging orientalised depictions of Muslim spaces. It is on display until 5 May.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity

You designed the V&A’s Ramadan Pavilion to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the Ramadan Tent Project’s annual Open Iftar festival. How did the project come about?

It started in 2018 through a conversation with a curator at the V&A. The V&A had already approached me to collect some of my drawings and sketchbooks as they were interested in the design processes around Muslim architecture in Britain today. Talking with a curator there, I said it would be interesting to build a representation of a UK mosque in the courtyard. There were initial obstacles, including fundraising and, of course, Covid-19, which meant it was delayed for longer than I expected, but it coincided quite nicely with the Ramadan Tent Projects’ 10-year anniversary.

What were the inspirations behind the design of the pavilion?

I’ve always been interested in how Muslim communities around the country have created and often built their own places of worship. It’s a step-by-step process that local communities go through. In that process, they create their own architectural language, where they pull together references from different Islamic forces while also incorporating their own surroundings. You end up getting this piecemeal composite and an assemblage of different styles. The Ramadan Pavillion visually pays homage to that creative process.

The colours we used are deliberately quite bold. I’ve often worked like that, partly because a lot of modern architecture has excluded colour and looks down on it. At the same time, incorporating colour was really a way of making it accessible to people, to make it a joyful, colourful object. I should also note that sustainability was a big part of the project too. All the materials we used were made of recyclable plywood. There is some steel in terms of brackets and support, but it was important for everyone involved that the materials used could eventually be repurposed.

As an architect, you’ve been working on mosque projects since the 2000s. Have any of them informed your approach to your current work?

The first mosques I was working on, one was here in Bethnal Green in east London. It was basically a row of portable cabins that they wanted to redevelop the whole site for. Then I did some work on mosques in Lewisham. Throughout that process I was very much involved in learning about the needs and aspirations of surrounding communities.

I found that initially many of their needs were immediate — needing certain amounts of space for prayers. It was very practical, and there wasn’t really any conversation about needing to create a spiritual or sacred place. This idea that we need to create architecture that is somehow sacred or spiritual is often discussed in western terms, and they didn’t really exist for the Muslim communities I was dealing with.

I also found that the way Muslim architecture was talked about in Britain was that the buildings were a bit shoddy, haphazard and a bit of a pastiche. Basically, that the mosques in repurposed buildings weren’t “real” architecture. That was strange, because in my work I could see that there was a real architectural process. We just needed to understand it in a different way. Eventually, I realised that these questions were rejecting the fact that we have more than 100 years of mosque building in Britain, and that we should be adding to that legacy rather than dismissing it. We don’t need to start from scratch. Muslims already have an architectural history in Britain.

In 2021, you created lifesize case studies of three London mosques for the Applied Arts Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale, which aimed to show the evolution of the UK mosques. What do you think that installation helped to reveal?

I think one of the things people took from the exhibit was that Muslims are quite adaptable and that anywhere could be used as a prayer space. One example that informed the project was the Wimbledon Mosque, which is at the end of a street laced with interwar suburban terraced houses. It’s this small white building with little minarets and a dome on top. I remember when I used to walk past it and think to myself, “How did this happen? What processes took place to create this phenomenal thing?”

The average age of British Muslims is quite young — 27 years old. With that in mind, how do you think mosques will evolve?

I think a good example of the change can be seen at the Cambridge Central Mosque, which has been trying to present itself as an “English”’ mosque, very much located within its contemporary community and environmentally sustainable.

I also imagine that much of the way people think about mosques will change on a social level. One issue is to do with gendered separation at mosques, where women will often have quite substandard access to the space and are probably the most excluded group. Many newer mosques are more explicit in addressing this problem, which also includes families. I think these social concerns will have to be addressed as mosques continue to grow and their congregations become larger and more diverse.

The biggest change, I think, will be less about the buildings of the mosques themselves and more about how they are funded and sustained. Right now, most mosques operate on a philanthropic model and rely on charitable donations, but I can certainly see some exploring investing in commercial ventures or seeing if they can add residential elements to the mosque. Of course, a commercial model might prove to be challenging if members of the congregation feel the mosque shouldn’t be getting involved in for-profit initiatives.

How will new technologies, such as the Metaverse and virtual reality, affect the way people interact with mosques?

Technology has allowed for different kinds of spaces to emerge. I know someone who started praying with a Sufi community online during the pandemic. When the lockdowns were lifted he started attending processions in real life. Online attendance is much larger now, owing to the increased audience they got during the Covid restrictions. Other technological advancements meant that women could create their own prayer spaces, which maybe they wouldn’t have had access to at their local mosques, but I do think it’s important for many mosques to maintain their physical presence, because performing prayer is such an embodied experience.

Newsletter

Newsletter